David Graeber’s vitriolic essay “Against Economics” in the New York Review of Books has generated responses from Noah Smith and Scott Sumner among others. I don’t disagree with much that Noah or Scott have to say, but I want to dig a little deeper than they did into some of Graeber’s arguments, because even though I think he is badly misinformed on many if not most of the subjects he writes about, I actually have some sympathy for his dissatisfaction with the current state of economics. Graeber wastes no time on pleasantries.

There is a growing feeling, among those who have the responsibility of managing large economies, that the discipline of economics is no longer fit for purpose. It is beginning to look like a science designed to solve problems that no longer exist.

A serious polemicist should avoid blatant mischaracterizations, exaggerations and cheap shots, and should be well-grounded in the object of his critique, thereby avoiding criticisms that undermine his own claims to expertise. I grant that Graeber has some valid criticisms to make, even agreeing with him, at least in part, on some of them. But his indiscriminate attacks on, and caricatures of, all neoclassical economics betrays a superficial understanding of that discipline.

Graeber begins by attacking what he considers the misguided and obsessive focus on inflation by economists.

A good example is the obsession with inflation. Economists still teach their students that the primary economic role of government—many would insist, its only really proper economic role—is to guarantee price stability. We must be constantly vigilant over the dangers of inflation. For governments to simply print money is therefore inherently sinful.

Every currency unit, or banknote issued by a central bank, now in circulation, as Graeber must know, has been “printed.” So to say that economists consider it sinful for governments to print money is either a deliberate falsehood, or an emotional rhetorical outburst, as Graeber immediately, and apparently unwittingly, acknowledges!

If, however, inflation is kept at bay through the coordinated action of government and central bankers, the market should find its “natural rate of unemployment,” and investors, taking advantage of clear price signals, should be able to ensure healthy growth. These assumptions came with the monetarism of the 1980s, the idea that government should restrict itself to managing the money supply, and by the 1990s had come to be accepted as such elementary common sense that pretty much all political debate had to set out from a ritual acknowledgment of the perils of government spending. This continues to be the case, despite the fact that, since the 2008 recession, central banks have been printing money frantically [my emphasis] in an attempt to create inflation and compel the rich to do something useful with their money, and have been largely unsuccessful in both endeavors.

Graeber’s use of the ambiguous pronoun “this” beginning the last sentence of the paragraph betrays his own confusion about what he is saying. Central banks are printing money and attempting to “create” inflation while supposedly still believing that inflation is a menace and printing money is a sin. Go figure.

We now live in a different economic universe than we did before the crash. Falling unemployment no longer drives up wages. Printing money does not cause inflation. Yet the language of public debate, and the wisdom conveyed in economic textbooks, remain almost entirely unchanged.

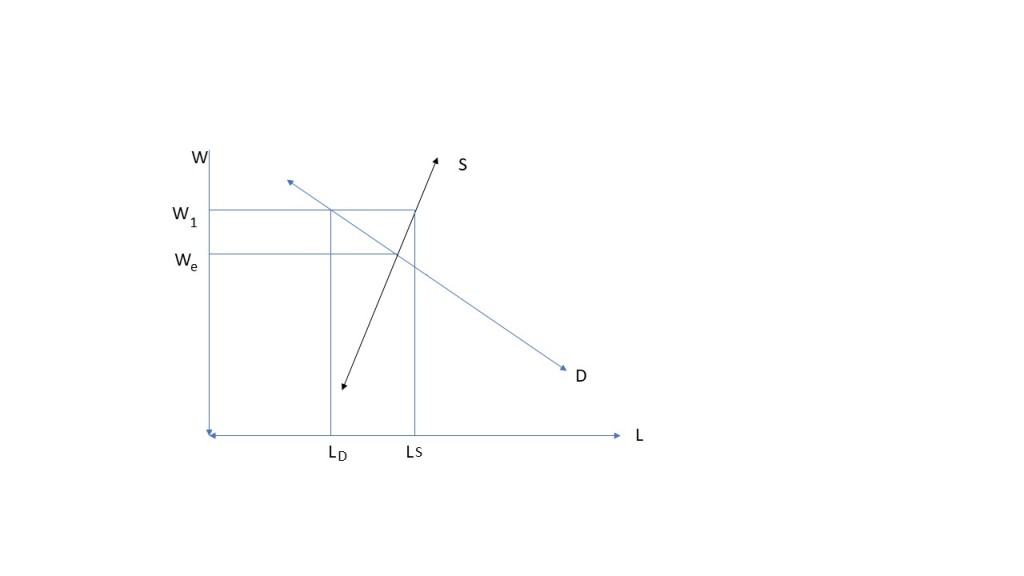

Again showing an inadequate understanding of basic economic theory, Graeber suggests that, in theory if not practice, falling unemployment should cause wages to rise. The Philips Curve, upon which Graeber’s suggestion relies, represents the empirically observed negative correlation between the rate of average wage increase and the rate of unemployment. But correlation does not imply causation, so there is no basis in economic theory to assert that falling unemployment causes the rate of increase in wages to accelerate. That the empirical correlation between unemployment and wage increases has not recently been in evidence provides no compelling reason for changing textbook theory.

From this largely unfounded and attack on economic theory – a theory which I myself consider, in many respects, inadequate and unreliable – Graeber launches a bitter diatribe against the supposed hegemony of economists over policy-making.

Mainstream economists nowadays might not be particularly good at predicting financial crashes, facilitating general prosperity, or coming up with models for preventing climate change, but when it comes to establishing themselves in positions of intellectual authority, unaffected by such failings, their success is unparalleled. One would have to look at the history of religions to find anything like it.

The ability to predict financial crises would be desirable, but that cannot be the sole criterion for whether economics has advanced our understanding of how economic activity is organized or what effects policy changes have. (I note parenthetically that many economists defensively reject the notion that economic crises are predictable on the grounds that if economists could predict a future economic crisis, those predictions would be immediately self-fulfilling. This response, of course, effectively disproves the idea that economists could predict that an economic crisis would occur in the way that astronomers predict solar eclipses. But this response slays a strawman. The issue is not whether economists can predict future crises, but whether they can identify conditions indicating an increased likelihood of a crisis and suggest precautionary measures to reduce the likelihood that a potential crisis will occur. But Graeber seems uninterested in or incapable of engaging the question at even this moderate level of subtlety.)

In general, I doubt that economists can make more than a modest contribution to improved policy-making, and the best that one can hope for is probably that they steer us away from the worst potential decisions rather than identifying the best ones. But no one, as far as I know, has yet been burned at the stake by a tribunal of economists.

To this day, economics continues to be taught not as a story of arguments—not, like any other social science, as a welter of often warring theoretical perspectives—but rather as something more like physics, the gradual realization of universal, unimpeachable mathematical truths. “Heterodox” theories of economics do, of course, exist (institutionalist, Marxist, feminist, “Austrian,” post-Keynesian…), but their exponents have been almost completely locked out of what are considered “serious” departments, and even outright rebellions by economics students (from the post-autistic economics movement in France to post-crash economics in Britain) have largely failed to force them into the core curriculum.

I am now happy to register agreement with something that Graeber says. Economists in general have become overly attached to axiomatic and formalistic mathematical models that create a false and misleading impression of rigor and mathematical certainty. In saying this, I don’t dispute that mathematical modeling is an important part of much economic theorizing, but it should not exclude other approaches to economic analysis and discourse.

As a result, heterodox economists continue to be treated as just a step or two away from crackpots, despite the fact that they often have a much better record of predicting real-world economic events. What’s more, the basic psychological assumptions on which mainstream (neoclassical) economics is based—though they have long since been disproved by actual psychologists—have colonized the rest of the academy, and have had a profound impact on popular understandings of the world.

That heterodox economists have a better record of predicting economic events than mainstream economists is an assertion for which Graeber offers no evidence or examples. I would not be surprised if he could cite examples, but one would have to weigh the evidence surrounding those examples before concluding that predictions by heterodox economists were more accurate than those of their mainstream counterparts.

Graeber returns to the topic of monetary theory, which seems a particular bugaboo of his. Taking the extreme liberty of holding up Mrs. Theresa May as a spokesperson for orthodox economics, he focuses on her definitive 2017 statement that there is no magic money tree.

The truly extraordinary thing about May’s phrase is that it isn’t true. There are plenty of magic money trees in Britain, as there are in any developed economy. They are called “banks.” Since modern money is simply credit, banks can and do create money literally out of nothing, simply by making loans. Almost all of the money circulating in Britain at the moment is bank-created in this way.

What Graeber chooses to ignore is that banks do not operate magically; they make loans and create deposits in seeking to earn profits; their decisions are not magical, but are oriented toward making profits. Whether they make good or bad decisions is debatable, but the debate isn’t about a magical process; it’s a debate about theory and evidence. Graeber describe how he thinks that economists think about how banks create money, correctly observing that there is a debate about how that process works, but without understanding those differences or their significance.

Economists, for obvious reasons, can’t be completely oblivious to the role of banks, but they have spent much of the twentieth century arguing about what actually happens when someone applies for a loan. One school insists that banks transfer existing funds from their reserves, another that they produce new money, but only on the basis of a multiplier effect). . . Only a minority—mostly heterodox economists, post-Keynesians, and modern money theorists—uphold what is called the “credit creation theory of banking”: that bankers simply wave a magic wand and make the money appear, secure in the confidence that even if they hand a client a credit for $1 million, ultimately the recipient will put it back in the bank again, so that, across the system as a whole, credits and debts will cancel out. Rather than loans being based in deposits, in this view, deposits themselves were the result of loans.

The one thing it never seemed to occur to anyone to do was to get a job at a bank, and find out what actually happens when someone asks to borrow money. In 2014 a German economist named Richard Werner did exactly that, and discovered that, in fact, loan officers do not check their existing funds, reserves, or anything else. They simply create money out of thin air, or, as he preferred to put it, “fairy dust.”

Graeber is right that economists differ in how they understand banking. But the simple transfer-of-funds view, a product of the eighteenth century, was gradually rejected over the course of the nineteenth century; the money-multiplier view largely superseded it, enjoying a half-century or more of dominance as a theory of banking, still remains a popular way for introductory textbooks to explain how banking works, though it would be better if it were decently buried and forgotten. But since James Tobin’s classic essay “Commercial banks as creators of money” was published in 1963, most economists who have thought carefully about banking have concluded that the amount of deposits created by banks corresponds to the quantity of deposits that the public, given their expectations about the future course of the economy and the future course of prices, chooses to hold. The important point is that while a bank can create deposits without incurring more than the negligible cost of making a book-keeping, or an electronic, entry in a customer’s account, the creation of a deposit is typically associated with a demand by the bank to hold either reserves in its account with the Fed or to hold some amount of Treasury instruments convertible, on very short notice, into reserves at the Fed.

Graeber seems to think that there is something fundamental at stake for the whole of macroeconomics in the question whether deposits created loans or loans create deposits. I agree that it’s an important question, but not as significant as Graeber believes. But aside from that nuance, what’s remarkable is that Graeber actually acknowledges that the weight of professional opinion is on the side that says that loans create deposits. He thus triumphantly cites a report by Bank of England economists that correctly explained that banks create money and do so in the normal course of business by making loans.

Before long, the Bank of England . . . rolled out an elaborate official report called “Money Creation in the Modern Economy,” replete with videos and animations, making the same point: existing economics textbooks, and particularly the reigning monetarist orthodoxy, are wrong. The heterodox economists are right. Private banks create money. Central banks like the Bank of England create money as well, but monetarists are entirely wrong to insist that their proper function is to control the money supply.

Graeber, I regret to say, is simply exposing the inadequacy of his knowledge of the history of economics. Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations explained that banks create money who, in doing so, saved the resources that would have been wasted on creating additional gold and silver. Subsequent economists from David Ricardo through Henry Thornton, J. S. Mill and R. G. Hawtrey were perfectly aware that banks can supply money — either banknotes or deposits — at less than the cost of mining and minting new coins, as they extend their credit in making loans to borrowers. So what is at issue, Graeber to the contrary notwithstanding, is not a dispute between orthodoxy and heterodoxy.

In fact, central banks do not in any sense control the money supply; their main function is to set the interest rate—to determine how much private banks can charge for the money they create.

Central banks set a rental price for reserves, thereby controlling the quantity of reserves into which bank deposits are convertible that is available to the economy. One way to think about that quantity is that the quantity of reserves along with the aggregate demand to hold reserves determines the exchange value of reserves and hence the price level; another way to think about it is that the interest rate or the implied policy stance of the central bank helps to determine the expectations of the public about the future course of the price level which is what determines – within some margin of error or range – what the future course of the price level will turn out to be.

Almost all public debate on these subjects is therefore based on false premises. For example, if what the Bank of England was saying were true, government borrowing didn’t divert funds from the private sector; it created entirely new money that had not existed before.

This is just silly. Funds may or may not be diverted from the private sector, but the total available resources to society is finite. If the central bank creates additional money, it creates additional claims to those resources and the creation of additional claims to resources necessarily has an effect on the prices of inputs and of outputs.

One might have imagined that such an admission would create something of a splash, and in certain restricted circles, it did. Central banks in Norway, Switzerland, and Germany quickly put out similar papers. Back in the UK, the immediate media response was simply silence. The Bank of England report has never, to my knowledge, been so much as mentioned on the BBC or any other TV news outlet. Newspaper columnists continued to write as if monetarism was self-evidently correct. Politicians continued to be grilled about where they would find the cash for social programs. It was as if a kind of entente cordiale had been established, in which the technocrats would be allowed to live in one theoretical universe, while politicians and news commentators would continue to exist in an entirely different one.

Even if we stipulate that this characterization of what the BBC and newspaper columnists believe is correct, what we would have — at best — is a commentary on the ability of economists to communicate their understanding of how the economy works to the intelligentsia that communicates to ordinary citizens. It is not in and of itself a commentary on the state of economic knowledge, inasmuch as Graeber himself concedes that most economists don’t accept monetarism. And that has been the case, as Noah Smith pointed out in his Bloomberg column on Graeber, since the early 1980s when the Monetarist experiment in trying to conduct monetary policy by controlling the monetary aggregates proved entirely unworkable and had to be abandoned as it was on the verge of precipitating a financial crisis.

Only after this long warmup decrying the sorry state of contemporary economic theory does Graeber begin discussing the book under review Money and Government by Robert Skidelsky.

What [Skidelsky] reveals is an endless war between two broad theoretical perspectives. . . The crux of the argument always seems to turn on the nature of money. Is money best conceived of as a physical commodity, a precious substance used to facilitate exchange, or is it better to see money primarily as a credit, a bookkeeping method or circulating IOU—in any case, a social arrangement? This is an argument that has been going on in some form for thousands of years. What we call “money” is always a mixture of both, and, as I myself noted in Debt (2011), the center of gravity between the two tends to shift back and forth over time. . . .One important theoretical innovation that these new bullion-based theories of money allowed was, as Skidelsky notes, what has come to be called the quantity theory of money (usually referred to in textbooks—since economists take endless delight in abbreviations—as QTM).

But these two perspectives are not mutually exclusive, and, depending on time, place, circumstances, and the particular problem that is the focus of attention, either of the two may be the appropriate paradigm for analysis.

The QTM argument was first put forward by a French lawyer named Jean Bodin, during a debate over the cause of the sharp, destablizing price inflation that immediately followed the Iberian conquest of the Americas. Bodin argued that the inflation was a simple matter of supply and demand: the enormous influx of gold and silver from the Spanish colonies was cheapening the value of money in Europe. The basic principle would no doubt have seemed a matter of common sense to anyone with experience of commerce at the time, but it turns out to have been based on a series of false assumptions. For one thing, most of the gold and silver extracted from Mexico and Peru did not end up in Europe at all, and certainly wasn’t coined into money. Most of it was transported directly to China and India (to buy spices, silks, calicoes, and other “oriental luxuries”), and insofar as it had inflationary effects back home, it was on the basis of speculative bonds of one sort or another. This almost always turns out to be true when QTM is applied: it seems self-evident, but only if you leave most of the critical factors out.

In the case of the sixteenth-century price inflation, for instance, once one takes account of credit, hoarding, and speculation—not to mention increased rates of economic activity, investment in new technology, and wage levels (which, in turn, have a lot to do with the relative power of workers and employers, creditors and debtors)—it becomes impossible to say for certain which is the deciding factor: whether the money supply drives prices, or prices drive the money supply.

As a matter of logic, if the value of money depends on the precious metals (gold or silver) from which coins were minted, the value of money is necessarily affected by a change in the value of the metals used to coin money. Because a large increase in the stock of gold and silver, as Graeber concedes, must reduce the value of those metals, subsequent inflation then being attributable, at least in part, to the gold and silver discoveries even if the newly mined gold and silver was shipped mainly to privately held Indian and Chinese hoards rather than minted into new coins. An exogenous increase in prices may well have caused the quantity of credit money to increase, but that is analytically distinct from the inflationary effect of a reduced value of gold or silver when, as was the case in the sixteenth century, money is legally defined as a specific weight of gold or silver.

Technically, this comes down to a choice between what are called exogenous and endogenous theories of money. Should money be treated as an outside factor, like all those Spanish dubloons supposedly sweeping into Antwerp, Dublin, and Genoa in the days of Philip II, or should it be imagined primarily as a product of economic activity itself, mined, minted, and put into circulation, or more often, created as credit instruments such as loans, in order to meet a demand—which would, of course, mean that the roots of inflation lie elsewhere?

There is no such choice, because any theory must posit certain initial conditions and definitions, which are given or exogenous to the analysis. How the theory is framed and which variables are treated as exogenous and which are treated as endogenous is a matter of judgment in light of the problem and the circumstances. Graeber is certainly correct that, in any realistic model, the quantity of money is endogenously, not exogenously, determined, but that doesn’t mean that the value of gold and silver may not usefully be treated as exogenous in a system in which money is defined as a weight of gold or silver.

To put it bluntly: QTM is obviously wrong. Doubling the amount of gold in a country will have no effect on the price of cheese if you give all the gold to rich people and they just bury it in their yards, or use it to make gold-plated submarines (this is, incidentally, why quantitative easing, the strategy of buying long-term government bonds to put money into circulation, did not work either). What actually matters is spending.

Graeber is talking in circles, failing to distinguish between the quantity theory of money – a theory about the value of a pure medium of exchange with no use except to be received in exchange — and a theory of the real value of gold and silver when money is defined as a weight of gold or silver. The value of gold (or silver) in monetary uses must be roughly equal to its value in non-monetary uses. which is determined by the total stock of gold and the demand to hold gold or to use it in coinage or for other uses (e.g., jewelry and ornamentation). An increase in the stock of gold relative to demand must reduce its value. That relationship between price and quantity is not the same as QTM. The quantity of a metallic money will increase as its value in non-monetary uses declines. If there is literally an unlimited demand for newly mined gold to be immediately sent unused into hoards, Graeber’s argument would be correct. But the fact that much of the newly mined gold initially went into hoards does not mean that all of the newly mined gold went into hoards.

In sum, Graeber is confused between the quantity theory of money and a theory of a commodity money used both as money and as a real commodity. The quantity theory of money of a pure medium of exchange posits that changes in the quantity of money cause proportionate changes in the price level. Changes in the quantity of a real commodity also used as money have nothing to do with the quantity theory of money.

Relying on a dubious account of the history of monetary theory by Skidelsky, Graeber blames the obsession of economists with the quantity theory for repeated monetary disturbances starting with the late 17th century deflation in Britain when silver appreciated relative to gold causing prices measured in silver to fall. Graeber thus fails to see that under a metallic money, real disturbances do have repercussion on the level of prices, repercussions having nothing to do with an exogenous prior change in the quantity of money.

According to Skidelsky, the pattern was to repeat itself again and again, in 1797, the 1840s, the 1890s, and, ultimately, the late 1970s and early 1980s, with Thatcher and Reagan’s (in each case brief) adoption of monetarism. Always we see the same sequence of events:

(1) The government adopts hard-money policies as a matter of principle.

(2) Disaster ensues.

(3) The government quietly abandons hard-money policies.

(4) The economy recovers.

(5) Hard-money philosophy nonetheless becomes, or is reinforced as, simple universal common sense.

There is so much indiscriminate generalization here that it is hard to know what to make of it. But the conduct of monetary policy has always been fraught, and learning has been slow and painful. We can and must learn to do better, but blanket condemnations of economics are unlikely to lead to better outcomes.

How was it possible to justify such a remarkable string of failures? Here a lot of the blame, according to Skidelsky, can be laid at the feet of the Scottish philosopher David Hume. An early advocate of QTM, Hume was also the first to introduce the notion that short-term shocks—such as Locke produced—would create long-term benefits if they had the effect of unleashing the self-regulating powers of the market:

Actually I agree that Hume, as great and insightful a philosopher as he was and as sophisticated an economic observer as he was, was an unreliable monetary theorist. And one of the reasons he was led astray was his unwarranted attachment to the quantity theory of money, an attachment that was not shared by his close friend Adam Smith.

Ever since Hume, economists have distinguished between the short-run and the long-run effects of economic change, including the effects of policy interventions. The distinction has served to protect the theory of equilibrium, by enabling it to be stated in a form which took some account of reality. In economics, the short-run now typically stands for the period during which a market (or an economy of markets) temporarily deviates from its long-term equilibrium position under the impact of some “shock,” like a pendulum temporarily dislodged from a position of rest. This way of thinking suggests that governments should leave it to markets to discover their natural equilibrium positions. Government interventions to “correct” deviations will only add extra layers of delusion to the original one.

I also agree that focusing on long-run equilibrium without regard to short-run fluctuations can lead to terrible macroeconomic outcomes, but that doesn’t mean that long-run effects are never of concern and may be safely disregarded. But just as current suffering must not be disregarded when pursuing vague and uncertain long-term benefits, ephemeral transitory benefits shouldn’t obscure serious long-term consequences. Weighing such alternatives isn’t easy, but nothing is gained by denying that the alternatives exist. Making those difficult choices is inherent in policy-making, whether macroeconomic or climate policy-making.

Although Graeber takes a valid point – that a supposed tendency toward an optimal long-run equilibrium does not justify disregard of an acute short-term problem – to an extreme, his criticism of the New Classical approach to policy-making that replaced the flawed mainstream Keynesian macroeconomics of the late 1970s is worth listening to. The New Classical approach self-consciously rejected any policy aimed at short-run considerations owing to a time-inconsistency paradox was based almost entirely on the logic of general-equilibrium theory and an illegitimate methodological argument rejecting all macroeconomic theories not rigorously deduced from the unarguable axiom of optimizing behavior by rational agents (and therefore not, in the official jargon, microfounded) as unscientific and unworthy of serious consideration in the brave New Classical world of scientific macroeconomics.

It’s difficult for outsiders to see what was really at stake here, because the argument has come to be recounted as a technical dispute between the roles of micro- and macroeconomics. Keynesians insisted that the former is appropriate to studying the behavior of individual households or firms, trying to optimize their advantage in the marketplace, but that as soon as one begins to look at national economies, one is moving to an entirely different level of complexity, where different sorts of laws apply. Just as it is impossible to understand the mating habits of an aardvark by analyzing all the chemical reactions in their cells, so patterns of trade, investment, or the fluctuations of interest or employment rates were not simply the aggregate of all the microtransactions that seemed to make them up. The patterns had, as philosophers of science would put it, “emergent properties.” Obviously, it was necessary to understand the micro level (just as it was necessary to understand the chemicals that made up the aardvark) to have any chance of understand the macro, but that was not, in itself, enough.

As an aisde, it’s worth noting that the denial or disregard of the possibility of any emergent properties by New Classical economists (of which what came to be known as New Keynesian economics is really a mildly schismatic offshoot) is nicely illustrated by the un-self-conscious alacrity with which the representative-agent approach was adopted as a modeling strategy in the first few generations of New Classical models. That New Classical theorists now insist that representative agency is not an essential to New Classical modeling is true, but the methodologically reductive nature of New Classical macroeconomics, in which all macroeconomic theories must be derived under the axiom of individually maximizing behavior except insofar as specific “frictions” are introduced by explicit assumption, is essential. (See here, here, and here)

The counterrevolutionaries, starting with Keynes’s old rival Friedrich Hayek . . . took aim directly at this notion that national economies are anything more than the sum of their parts. Politically, Skidelsky notes, this was due to a hostility to the very idea of statecraft (and, in a broader sense, of any collective good). National economies could indeed be reduced to the aggregate effect of millions of individual decisions, and, therefore, every element of macroeconomics had to be systematically “micro-founded.”

Hayek’s role in the microfoundations movement is important, but his position was more sophisticated and less methodologically doctrinaire than that of the New Classical macroeconomists, if for no other reason than that Hayek didn’t believe that macroeconomics should, or could, be derived from general-equilibrium theory. His criticism, like that of economists like Clower and Leijonhufvud, of Keynesian macroeconomics for being insufficiently grounded in microeconomic principles, was aimed at finding microeconomic arguments that could explain and embellish and modify the propositions of Keynesian macroeconomic theory. That is the sort of scientific – not methodological — reductivism that Hayek’s friend Karl Popper advocated: a theoretical and empirical challenge of reducing a higher level theory to its more fundamental foundations, e.g., when physicists and chemists search for theoretical breakthroughs that allow the propositions of chemistry to be reduced to more fundamental propositions of physics. The attempt to reduce chemistry to underlying physical principles is very different from a methodological rejection of all chemistry that cannot be derived from underlying deep physical theories.

There is probably more than a grain of truth in Graeber’s belief that there was a political and ideological subtext in the demand for microfoundations by New Classical macroeconomists, but the success of the microfoundations program was also the result of philosophically unsophisticated methodological error. How to apportion the share of blame going to mistaken methodology, professional and academic opportunism, and a hidden political agenda is a question worthy of further investigation. The easy part is to identify the mistaken methodology, which Graeber does. As for the rest, Graeber simply asserts bad faith, but with little evidence.

In Graeber’s comprehensive condemnation of modern economics, the efficient market hypothesis, being closely related to the rational-expectations hypothesis so central to New Classical economics, is not spared either. Here again, though I share and sympathize with his disdain for EMH, Graeber can’t resist exaggeration.

In other words, we were obliged to pretend that markets could not, by definition, be wrong—if in the 1980s the land on which the Imperial compound in Tokyo was built, for example, was valued higher than that of all the land in New York City, then that would have to be because that was what it was actually worth. If there are deviations, they are purely random, “stochastic” and therefore unpredictable, temporary, and, ultimately, insignificant.

Of course, no one is obliged to pretend that markets could not be wrong — and certainly not by a definition. The EMH simply asserts that the price of an asset reflects all the publicly available information. But what EMH asserts is certainly not true in many or even most cases, because people with non-public information (or with superior capacity to process public information) may affect asset prices, and such people may profit at the expense of those less knowledgeable or less competent in anticipating price changes. Moreover, those advantages may result from (largely wasted) resources devoted to acquiring and processing information, and it is those people who make fortunes betting on the future course of asset prices.

Graeber then quotes Skidelsky approvingly:

There is a paradox here. On the one hand, the theory says that there is no point in trying to profit from speculation, because shares are always correctly priced and their movements cannot be predicted. But on the other hand, if investors did not try to profit, the market would not be efficient because there would be no self-correcting mechanism. . .

Secondly, if shares are always correctly priced, bubbles and crises cannot be generated by the market….

This attitude leached into policy: “government officials, starting with [Fed Chairman] Alan Greenspan, were unwilling to burst the bubble precisely because they were unwilling to even judge that it was a bubble.” The EMH made the identification of bubbles impossible because it ruled them out a priori.

So the apparent paradox that concerns Skidelsky and Graeber dissolves upon (only a modest amount of) further reflection. Proper understanding and revision of the EMH makes it clear that bubbles can occur. But that doesn’t mean that bursting bubbles is a job that can be safely delegated to any agency, including the Fed.

Moreover, the housing bubble peaked in early 2006, two and a half years before the financial crisis in September 2008. The financial crisis was not unrelated to the housing bubble, which undoubtedly added to the fragility of the financial system and its vulnerability to macroeconomic shocks, but the main cause of the crisis was Fed policy that was unnecessarily focused on a temporary blip in commodity prices persuading the Fed not to loosen policy in 2008 during a worsening recession. That was a scenario similar to the one in 1929 when concern about an apparent stock-market bubble caused the Fed to repeatedly tighten money, raising interest rates, thereby causing a downturn and crash of asset prices triggering the Great Depression.

Graeber and Skidelsky correctly identify some of the problems besetting macroeconomics, but their indiscriminate attack on all economic theory is unlikely to improve the situation. A pity, because a focused and sophisticated critique of economics than they have served up has never been more urgently needed than it is now to enable economists to perform the modest service to mankind of which they might be capable.