I have been writing recently about two great papers by McCloskey and Zecher (“How the Gold Standard Really Worked” and “The Success of Purchasing Power Parity”) on the gold standard and the price-specie-flow mechanism (PSFM). This post, for the time being at any rate, will be the last in the series. My main topic in this post is the four-month burst of inflation in the US from April through July of 1933, an episode that largely escaped the notice of Friedman and Schwartz in their Monetary History of the US, an omission criticized by McCloskey and Zecher in their purchasing-power-parity paper. (I will mention parenthetically that the 1933 inflation was noticed and its importance understood by R. G. Hawtrey in the second (1933) edition of his book Trade Depression and the Way Out and by Scott Sumner in his 2015 book The Midas Paradox. Both Hawtrey and Sumner emphasize the importance of the aborted 1933 recovery as have Jalil and Rua in an important recent paper.) In his published comment on the purchasing-power-parity paper, Friedman (pp. 157-62) responded to the critique by McCloskey and Zecher, and I will look carefully at that response below. But before discussing Friedman’s take on the 1933 inflation, I want to make four general comments about the two McCloskey and Zecher papers.

My first comment concerns an assertion made in a couple of places in which they interpret balance-of-payments surpluses or deficits under a fixed-exchange-rate regime as the mechanism by which excess demands for (supplies of) money in one country are accommodated by way of a balance-of-payments surpluses (deficits). Thus, given a fixed exchange rate between country A and country B, if the quantity of money in country A is less than the amount that the public in country A want to hold, the amount of money held in country A will be increased as the public, seeking to add to their cash holdings, collectively spend less than their income, thereby generating an export surplus relative to country B, and inducing a net inflow of country B’s currency into country A to be converted into country A’s currency at the fixed exchange rate. The argument is correct, but it glosses over a subtle point: excess supplies of, and excess demands for, money in this context are not absolute, but comparative. Money flows into whichever country has the relatively larger excess demand for money. Both countries may have an absolute excess supply of money, but the country with the comparatively smaller excess supply of money will nevertheless experience a balance-of-payments surplus and an inflow of cash.

My second comment is that although McCloskey and Zecher are correct to emphasize that the quantity of money in a country operating with a fixed exchange is endogenous, they fail to mention explicitly that, apart from the balance-of-payments mechanism under fixed exchange rates, the quantity of domestically produced inside money is endogenous, because there is a domestic market mechanism that adjusts the amount of inside money supplied by banks to the amount of inside money demanded by the public. Thus, under a fixed-exchange-rate regime, the quantity of inside money and the quantity of outside money are both endogenously determined, the quantity of inside money being determined by domestic forces, and the quantity of outside money determined by international forces operating through the balance-of-payments mechanism.

Which brings me to my third comment. McCloskey and Zecher have a two-stage argument. The first stage is that commodity arbitrage effectively constrains the prices of tradable goods in all countries linked by international trade. Not all commodities are tradable, and even tradable goods may be subject to varying limits — based on varying ratios of transportation costs to value — on the amount of price dispersion consistent with the arbitrage constraint. The second stage of their argument is that insofar as the prices of tradable goods are constrained by arbitrage, the rest of the price system is also effectively constrained, because economic forces constrain all relative prices to move toward their equilibrium values. So if the nominal prices of tradable goods are fixed by arbitrage, the tendency of relative prices between non-tradables and tradables to revert to their equilibrium values must constrain the nominal prices of non-tradable goods to move in the same direction as tradable-goods prices are moving. I don’t disagree with this argument in principle, but it’s subject to at least two qualifications.

First, monetary policy can alter spending patterns; if the monetary authority wishes, it can accumulate the inflow of foreign exchange that results when there is a domestic excess demand for money rather than allow the foreign-exchange inflow to increase the domestic money stock. If domestic money mostly consists of inside money supplied by private banks, preventing an increase in the quantity of inside money may require increasing the legal reserve requirements to which banks are subject. By not allowing the domestic money stock to increase in response to a foreign-exchange inflow, the central bank effectively limits domestic spending, thereby reducing the equilibrium ratio between the prices of non-tradables and tradables. A monetary policy that raises the relative price of tradables to non-tradables was called exchange-rate protection by the eminent Australian economist Max Corden. Although term “currency manipulation” is chronically misused to refer to any exchange-rate depreciation, the term is applicable to the special case in which exchange-rate depreciation is combined with a tight monetary policy thereby sustaining a reduced exchange rate.

Second, Although McCloskey and Zecher are correct that equilibrating forces normally cause the prices of non-tradables to move in the direction toward which arbitrage is forcing the prices of tradables to move, such equilibrating processes need not always operate powerfully. Suppose, to go back to David Hume’s classic thought experiment, the world is on a gold standard and the amount of gold in Britain is doubled while the amount of gold everywhere else is halved, so that the total world stock of gold is unchanged, just redistributed from the rest of the world to Britain. Under the PSFM view of the world, prices instantaneously double in Britain and fall by half in the rest of the world, and it only by seeking bargains in the rest of the world that Britain gradually exports gold to import goods from the rest of the world. Prices gradually fall in Britain and rise in the rest of the world; eventually (and as a first approximation) prices and the distribution of gold revert back to where they were originally. Alternatively, in the arbitrage view of the world, the prices of tradables don’t change, because in the world market for tradables, neither the amount of output nor the amount of gold has changed, so why should the price of tradables change? But if prices of tradables don’t change, does that mean that the prices of non-tradables won’t change? McCloskey and Zecher argue that if arbitrage prevents the prices of tradables from changing, the equilibrium relationship between the prices of tradables and non-tradables will also prevent the prices of non-tradables from changing.

I agree that the equilibrium relationship between the prices of tradables and non-tradables imposes some constraint on the movement of the prices of non-tradables, but the equilibrium relationship between the prices of tradables and non-tradables is not necessarily a constant. If people in Britain suddenly have more gold in their pockets, and they can buy all the tradable goods they want at unchanged prices, they may well increase their demand for non-tradables, causing the prices of British non-tradables to rise relative to the prices of tradables. The terms of trade will shift in Britain’s favor. Nevertheless, it would be very surprising if the price of non-tradables were to double, even momentarily, as the Humean PSFM argument suggests. Just because arbitrage does not strictly constrain the price of non-tradables does not mean that the appropriate default assumption is that the prices of non-tradables would rise by as much as suggested by a naïve quantity-theoretic PSFM extrapolation. Thus, the way to think of the common international price level under a fixed-exchange-rate regime is that the national price levels are linked by arbitrage, so that movements in national price levels are highly — but not necessarily perfectly — correlated.

My fourth comment is terminological. As Robert Lipsey (pp. 151-56) observes in his published comment about the McCloskey-Zecher paper on purchasing power parity (PPP), when the authors talk about PPP, they usually have in mind the narrower concept of the law of one price which says that commodity arbitrage keeps the prices of the same goods at different locations from deviating by more than the cost of transportation. Thus, a localized increase in the quantity of money at any location cannot force up the price of that commodity at that location by an amount exceeding the cost of transporting that commodity from the lowest cost alternative source of supply of that commodity. The quantity theory of money cannot operate outside the limits imposed by commodity arbitrage. That is the fundamental mistake underlying the PSFM.

PPP is a weaker proposition than the law of one price, refering to the relationship between exchange rates and price indices. If domestic price indices in two locations with different currencies rise by different amounts, PPP says that the expected change in the exchange rate between the two currencies is proportional to relative change in the price indices. But PPP is only an approximate relationship, while the law of one price is, within the constraints of transportation costs, an exact relationship. If all goods are tradable and transportation costs are zero, prices of all commodities sold in both locations will be equal. However, the price indices for the two location will not have the same composition, goods not being produced or consumed in the same proportions in the two locations. Thus, even if all goods sold in both locations sell at the same prices the price indices for the two locations need not change by the same proportions. If the price of a commodity exported by country A goes up relative to the price of the good exported by country B, the exchange rate between the two countries will change even if the law of one price is always satisfied. As I argued in part II of this series on PSFM, it was this terms-of-trade effect that accounted for the divergence between American and British price indices in the aftermath of the US resumption of gold convertibility in 1879. The law of one price can hold even if PPP doesn’t.

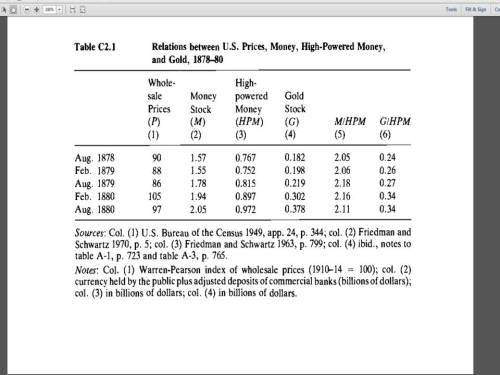

With those introductory comments out of the way, let’s now examine the treatment of the 1933 inflation in the Monetary History. The remarkable thing about the account of the 1933 inflation given by Friedman and Schwartz is that they treat it as if it were a non-event. Although industrial production increased by over 45% in a four-month period, accompanied by a 14% rise in wholesale prices, Friedman and Schwartz say almost nothing about the episode. Any mention of the episode is incidental to their description of the longer cyclical movements described in Chapter 9 of the Monetary History entitled “Cyclical Changes, 1933-41.” On p. 493, they observe: “the most notable feature of the revival after 1933 was not its rapidity but its incompleteness,” failing to mention that the increase of over 45% in industrial production from April to July was the largest increase industrial production over any four-month period (or even any 12-month period) in American history. In the next paragraph, Friedman and Schwartz continue:

The revival was initially erratic and uneven. Reopening of the banks was followed by rapid spurt in personal income and industrial production. The spurt was intensified by production in anticipation of the codes to be established under the National Industrial Recovery Act (passed June 16, 1933), which were expected to raise wage rates and prices, and did. (pp. 493-95)

Friedman and Schwartz don’t say anything about the suspension of convertibility by FDR and the devaluation of the dollar, all of which caused wholesale prices to rise immediately and substantially (14% in four months). It is implausible to think that the huge increase in industrial production and in wholesale prices was caused by the anticipation of increased wages and production quotas that would take place only after the NIRA was implemented, i.e., not before August. The reopening of the banks may have had some effect, but it is hard to believe that the effect would have accounted for more than a small fraction of the total increase or that it would have had a continuing effect over a four-month period. In discussing the behavior of prices, Friedman and Schwartz, write matter-of-factly:

Like production, wholesale prices first spurted in early 1933, partly for the same reason – in anticipation of the NIRA codes – partly under the stimulus of depreciation in the foreign exchange value of the dollar. (p. 496)

This statement is troubling for two reasons: 1) it seems to suggest that anticipation of the NIRA codes was at least as important as dollar depreciation in accounting for the rise in wholesale prices; 2) it implies that depreciation of the dollar was no more important than anticipation of the NIRA codes in accounting for the increase in industrial production. Finally, Friedman and Schwartz assess the behavior of prices and output over the entire 1933-37 expansion.

What accounts for the greater rise in wholesale prices in 1933-37, despite a probably higher fraction of the labor force unemployed and of physical capacity unutilized than in the two earlier expansions [i.e., 1879-82, 1897-1900]? One factor, already mentioned, was devaluation with its differential effect on wholesale prices. Another was almost surely the explicit measures to raise prices and wages undertaken with government encouragement and assistance, notably, NIRA, the Guffey Coal Act, the agricultural price-support program, and National Labor Relations Act. The first two were declared unconstitutional and lapsed, but they had some effect while in operation; the third was partly negated by Court decisions and then revised, but was effective throughout the expansion; the fourth, along with the general climate of opinion it reflected, became most important toward the end of the expansion.

There has been much discussion in recent years of a wage-price spiral or price-wage spiral as an explanation of post-World War II price movements. We have grave doubts that autonomous changes in wages and prices played an important role in that period. There seems to us a much stronger case for a wage-price or price-wage spiral interpretation of 1933-37 – indeed this is the only period in the near-century we cover for which such an explanation seems clearly justified. During those years there were autonomous forces raising wages and prices. (p. 498)

McCloskey and Zecher explain the implausibility of the idea that the 1933 burst of inflation (mostly concentrated in the April-July period) that largely occurred before NIRA was passed and almost completely occurred before the NIRA was implemented could be attributed to the NIRA.

The chief factual difficulties with the notion that the official cartels sanctioned by the NRA codes caused a rise in the general price level is that most of the NRA codes were not enacted until after the price rise. Ante hoc ergo non propter hoc. Look at the plot of wholesale prices of 1933 in figure 2.3 (retail prices, including such nontradables as housing, show a similar pattern). Most of the rise occurs in May, June, and July of 1933, but the NIRA was not even passed until June. A law passed, furthermore, is not a law enforced. However eager most businessmen must have been to cooperate with a government intent on forming monopolies, the formation took time. . . .

By September 1933, apparently before the approval of most NRA codes — and, judging from the late coming of compulsion, before the effective approval of agricultural codes-three-quarters of the total rise in wholesale prices and more of the total rise in retail food prices from March 1933 to the average of 1934 was complete. On the face of it, at least, the NRA is a poor candidate for a cause of the price rise. It came too late.

What came in time was the depreciation of the dollar, a conscious policy of the Roosevelt administration from the beginning. . . . There was certainly no contemporaneous price rise abroad to explain the 28-percent rise in American wholesale prices (and in retail food prices) between April 1933 and the high point in September 1934. In fact, in twenty-five countries the average rise was only 2.2 percent, with the American rise far and away the largest.

It would appear, in short, that the economic history of 1933 cannot be understood with a model closed to direct arbitrage. The inflation was no gradual working out of price-specie flow; less was it an inflation of aggregate demand. It happened quickly, well before most other New Deal policies (and in particular the NRA) could take effect, and it happened about when and to the extent that the dollar was devalued. By the standard of success in explaining major events, parity here works. (pp. 141-43)

In commenting on the McCloskey-Zecher paper, Friedman responds to their criticism of account of the 1933 inflation presented in the Monetary History. He quibbles about the figure in which McCloskey and Zecher showed that US wholesale prices were highly correlated with the dollar/sterling exchange rate after FDR suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold in April, complaining that chart leaves the impression that the percentage increase in wholesale prices was as large as the 50% decrease in the dollar/sterling exchange rate, when in fact it was less than a third as large. A fair point, but merely tangential to the main issue: explaining the increase in wholesale prices. The depreciation in the dollar can explain the increase in wholesale prices even if the increase in wholesale prices is not as great as the depreciation of the dollar. Friedman continues:

In any event, as McCloskey and Zecher note, we pointed out in A Monetary History that there was a direct effect of devaluation on prices. However, the existence of a direct effect on wholesale prices is not incompatible with the existence of many other prices, as Moe Abramovitz has remarked, such as non-tradable-goods prices, that did not respond immediately or responded to different forces. An index of rents paid plotted against the exchange rate would not give the same result. An index of wages would not give the same result. (p. 161)

In saying that the Monetary History acknowledged that there was a direct effect of devaluation on prices, Friedman is being disingenuous; by implication at least, the Monetary History suggests that the importance of the NIRA for rising prices and output even in the April to July 1933 period was not inferior to the effect of devaluation on prices and output. Though (belatedly) acknowledging the primary importance of devaluation on wholesale prices, Friedman continues to suggest that factors other than devaluation could have accounted for the rise in wholesale prices — but (tellingly) without referring to the NIRA. Friedman then changes the subject to absence of devaluation effects on the prices of non-tradable goods and on wages. Thus, he is left with no substantial cause to explain the sudden rise in US wholesale prices between April and July 1933 other than the depreciation of the dollar, not the operation of PSFM. Friedman and Schwartz could easily have consulted Hawtrey’s definitive contemporaneous account of the 1933 inflation, but did not do so, referring only once to Hawtrey in the Monetary History (p. 99) in connection with changes by the Bank of England in Bank rate in 1881-82.

Having been almost uniformly critical of Friedman, I would conclude with a word on his behalf. In the context of Great Depression, I think there are good reasons to think that devaluation would not necessarily have had a significant effect on wages and the prices of non-tradables. At the bottom of a downturn, it’s likely that relative prices are far from their equilibrium values. So if we think of devaluation as a mechanism for recovery and restoring an economy to the neighborhood of equilibrium, we would not expect to see prices and wages rising uniformly. So if, for the sake of argument, we posit that real wages were in some sense too high at the bottom of the recession, we would not necessarily expect that a devaluation would cause wages (or the prices of non-tradables) to rise proportionately with wholesale prices largely determined in international markets. Friedman actually notes that the divergence between the increase of wholesale prices and the increase in the implicit price deflator in 1933-37 recovery was larger than in the 1879-82 or the 1897-99 recoveries. The magnitude of the necessary relative price adjustment in the 1933-37 episode may have been substantially greater than it was in either of the two earlier episodes.