I have been working on a paper tentatively titled “The Smithian and Humean Traditions in Monetary Theory.” One section of the paper is on the price-specie-flow mechanism, about which I wrote last month in my previous post. This section develops the arguments of the previous post at greater length and draws on a number of earlier posts that I’ve written about PSFM as well (e.g., here and here )provides more detailed criticisms of both PSFM and sterilization and provides some further historical evidence to support some of the theoretical arguments. I will be grateful for any comments and feedback.

The tortured intellectual history of the price-specie-flow mechanism (PSFM) received its still classic exposition in a Hume (1752) essay, which has remained a staple of the theory of international adjustment under the gold standard, or any international system of fixed exchange rates. Regrettably, the two-and-a-half-century life span of PSFM provides no ground for optimism about the prospects for progress in what some are pleased to call without irony economic science.

PSFM describes how, under a gold standard, national price levels tend to be equalized, with deviations between the national price levels in any two countries inducing gold to be shipped from the country with higher prices to the one with lower prices until prices are equalized. Premised on a version of the quantity theory of money in which (1) the price level in each country on the gold standard is determined by the quantity of money in that country, and (2) money consists entirely in gold coin or bullion, Hume elegantly articulated a model of disturbance and equilibration after an exogenous change in the gold stock in one country.

Viewing banks as inflationary engines of financial disorder, Hume disregarded banks and the convertible monetary liabilities of banks in his account of PSFM, leaving to others the task of describing the international adjustment process under a gold standard with fractional-reserve banking. The task of devising an institutional framework, within which PSFM could operate, for a system of fractional-reserve banking proved to be problematic and ultimately unsuccessful.

For three-quarters of a century, PSFM served a purely theoretical function. During the Bullionist debates of the first two decades of the nineteenth century, triggered by the suspension of the convertibility of the pound sterling into gold in 1797, PSFM served as a theoretical benchmark not a guide for policy, it being generally assumed that, when convertibility was resumed, international monetary equilibrium would be restored automatically.

However, the 1821 resumption was followed by severe and recurring monetary disorders, leading some economists, who formed what became known as the Currency School, to view PSFM as a normative criterion for ensuring smooth adjustment to international gold flows. That criterion, the Currency Principle, stated that the total currency in circulation in Britain should increase or decrease by exactly as much as the amount of gold flowing into or out of Britain.[1]

The Currency Principle was codified by the Bank Charter Act of 1844. To mimic the Humean mechanism, it restricted, but did not suppress, the right of note-issuing banks in England and Wales, which were allowed to continue issuing notes, at current, but no higher, levels, without holding equivalent gold reserves. Scottish and Irish note-issuing banks were allowed to continue issuing notes, but could increase their note issue only if matched by increased holdings of gold or government debt. In England and Wales, the note issue could increase only if gold was exchanged for Bank of England notes, so that a 100-percent marginal gold reserve requirement was imposed on additional banknotes.

Opposition to the Bank Charter Act was led by the Banking School, notably John Fullarton and Thomas Tooke. Rejecting the Humean quantity-theoretic underpinnings of the Currency School and the Bank Charter Act, the Banking School rejected the quantitative limits of the Bank Charter Act as both unnecessary and counterproductive, because banks, obligated to redeem their liabilities directly or indirectly in gold, issue liabilities only insofar as they expect those liabilities to be willingly held by the public, or, if not, are capable of redeeming any liabilities no longer willingly held. Rather than the Humean view that banks issue banknotes or create deposits without constraint, the Banking School held Smith’s view that banks issue money in a form more convenient to hold and to transact with than metallic money, so that bank money allows an equivalent amount of gold to be shifted from monetary to real (non-monetary) uses, providing a net social savings. For a small open economy, the diversion (and likely export) of gold bullion from monetary to non-monetary uses has negligible effect on prices (which are internationally, not locally, determined).

The quarter century following enactment of the Bank Charter Act showed that the Act had not eliminated monetary disturbances, the government having been compelled to suspend the Act in 1847, 1857 and 1866 to prevent incipient crises from causing financial collapse. Indeed, it was precisely the fear that liquidity might not be forthcoming that precipitated increased demands for liquidity that the Act made it impossible to accommodate. Suspending the Act was sufficient to end the crises with limited intervention by the Bank. [check articles on the crises of 1847, 1857 and 1866.]

It may seem surprising, but the disappointing results of the Bank Charter Act provided little vindication to the Banking School. It led only to a partial, uneasy, and not entirely coherent, accommodation between PSFM doctrine and the reality of a monetary system in which the money stock consists mostly of banknotes and bank deposits issued by fractional-reserve banks. But despite the failure of the Bank Charter Act, PSFM achieved almost canonical status, continuing, albeit with some notable exceptions, to serve as the textbook model of the gold standard.

The requirement that gold flows induce equal changes in the quantity of money within a country into (or from) which gold is flowing was replaced by an admonition that gold flows lead to “appropriate” changes in the central-bank discount rate or an alternative monetary instrument to cause the quantity of money to change in the same direction as the gold flow. While such vague maxims, sometimes described as “the rules of the game,” gave only directional guidance about how to respond to change in gold reserves, their hortatory character, and avoidance of quantitative guidance, allowed monetary authorities latitude to avoid the self-inflicted crises that had resulted from the quantitative limits of the Bank Charter Act.

Nevertheless, the myth of vague “rules” relating the quantity of money in a country to changes in gold reserves, whose observance ensured the smooth functioning of the international gold standard before its collapse at the start of World War I, enshrined PSFM as the theoretical paradigm for international monetary adjustment under the gold standard.

That paradigm was misconceived in four ways that can be briefly summarized.

- Contrary to PSFM, changes in the quantity of money in a gold-standard country cannot change local prices proportionately, because prices of tradable goods in that country are constrained by arbitrage to equal the prices of those goods in other countries.

- Contrary to PSFM, changes in local gold reserves are not necessarily caused either by non-monetary disturbances such as shifts in the terms of trade between countries or by local monetary disturbances (e.g. overissue by local banks) that must be reversed or counteracted by central-bank policy.

- Contrary to PSFM, changes in the national price levels of gold-standard countries were uncorrelated with gold flows, and changes in national price levels were positively, not negatively, correlated.

- Local banks and monetary authorities exhibit their own demands for gold reserves, demands exhibited by choice (i.e., independent of legally required gold holdings) or by law (i.e., by legally requirement to hold gold reserves equal to some fraction of banknotes issued by banks or monetary authorities). Such changes in gold reserves may be caused by changes in the local demands for gold by local banks and the monetary authorities in one or more countries.

Many of the misconceptions underlying PSFM were identified by Fullarton’s refutation of the Currency School. In articulating the classical Law of Reflux, he established the logical independence of the quantity convertible money in a country from by the quantity of gold reserves held by the monetary authority. The gold reserves held by individual banks, or their deposits with the Bank of England, are not the raw material from which banks create money, either banknotes or deposits. Rather, it is their creation of banknotes or deposits when extending credit to customers that generates a derived demand to hold liquid assets (i.e., gold) to allow them to accommodate the demands of customers and other banks to redeem banknotes and deposits. Causality runs from creating banknotes and deposits to holding reserves, not vice versa.

The misconceptions inherent in PSFM and the resulting misunderstanding of gold flows under the gold standard led to a further misconception known as sterilization: the idea that central banks, violating the obligations imposed by “the rules of the game,” do not allow, or deliberately prevent, local money stocks from changing as their gold holdings change. The misconception is the presumption that gold inflows ought necessarily cause increases in local money stocks. The mechanisms causing local money stocks to change are entirely different from those causing gold flows. And insofar as those mechanisms are related, causality flows from the local money stock to gold reserves, not vice versa.

Gold flows also result when monetary authorities transform their own asset holdings into gold. Notable examples of such transformations occurred in the 1870s when a number of countries abandoned their de jure bimetallic (and de facto silver) standards to the gold standard. Monetary authorities in those countries transformed silver holdings into gold, driving the value of gold up and silver down. Similarly, but with more catastrophic consequences, the Bank of France, in 1928 after France restored the gold standard, began redeeming holdings of foreign-exchange reserves (financial claims on the United States or Britain, payable in gold) into gold. Following the French example, other countries rejoining the gold standard redeemed foreign exchange for gold, causing gold appreciation and deflation that led to the Great Depression.

Rereading the memoirs of this splendid translation . . . has impressed me with important subtleties that I missed when I read the memoirs in a language not my own and in which I am far from completely fluent. Had I fully appreciated those subtleties when Anna Schwartz and I were writing our A Monetary History of the United States, we would likely have assessed responsibility for the international character of the Great Depression somewhat differently. We attributed responsibility for the initiation of a worldwide contraction to the United States and I would not alter that judgment now. However, we also remarked, “The international effects were severe and the transmission rapid, not only because the gold-exchange standard had rendered the international financial system more vulnerable to disturbances, but also because the United States did not follow gold-standard rules.” Were I writing that sentence today, I would say “because the United States and France did not follow gold-standard rules.”

I pause to note for the record Friedman’s assertion that the United States and France did not follow “gold-standard rules.” Warming up to the idea, he then accused them of sterilization.

Benjamin Strong and Emile Moreau were admirable characters of personal force and integrity. But . . .the common policies they followed were misguided and contributed to the severity and rapidity of transmission of the U.S. shock to the international community. We stressed that the U.S. “did not permit the inflow of gold to expand the U.S. money stock. We not only sterilized it, we went much further. Our money stock moved perversely, going down as the gold stock went up” from 1929 to 1931.

Strong and Moreau tried to reconcile two ultimately incompatible objectives: fixed exchange rates and internal price stability. Thanks to the level at which Britain returned to gold in 1925, the U.S. dollar was undervalued, and thanks to the level at which France returned to gold at the end of 1926, so was the French franc. Both countries as a result experienced substantial gold inflows. Gold-standard rules called for letting the stock of money rise in response to the gold inflows and for price inflation in the U.S. and France, and deflation in Britain, to end the over-and under-valuations. But both Strong and Moreau were determined to prevent inflation and accordingly both sterilized the gold inflows, preventing them from providing the required increase in the quantity of money.

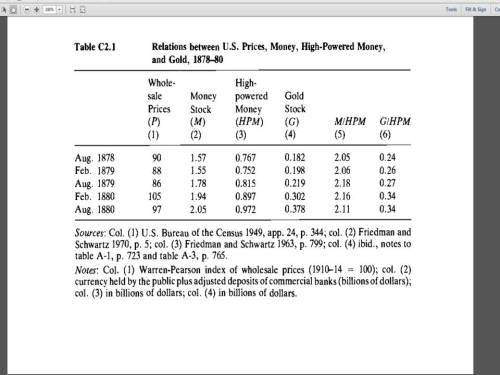

Friedman’s discussion of sterilization is at odds with basic theory. Working with a naïve version of PSFM, he imagines that gold flows passively respond to trade balances independent of monetary forces, and that the monetary authority under a gold standard is supposed to ensure that the domestic money stock varies roughly in proportion to its gold reserves. Ignoring the international deflationary dynamic, he asserts that the US money stock perversely declined from 1929 to 1931, while its gold stock increased. With a faltering banking system, the public shifted from holding demand deposits to currency. Gold reserves were legally required against currency, but not against demand deposits, so the shift from deposits to currency entailed an increase gold reserves. To be sure the increased US demand for gold added to upward pressure on value of gold, and to worldwide deflationary pressure. But US gold holdings rose by only $150 million from December 1929 to December 1931 compared with an increase of $1.06 billion in French gold holdings over the same period. Gold accumulation by the US and its direct contribution to world deflation during the first two years of the Depression was small relative to that of France.

Friedman also erred in stating “the common policies they followed were misguided and contributed to the severity and rapidity of transmission of the U.S. shock to the international community.” The shock to the international community clearly originated not in the US but in France. The Fed could have absorbed and mitigated the shock by allowing a substantial outflow of its huge gold reserves, but instead amplified the shock by raising interest rates to nearly unprecedented levels, causing gold to flow into the US.

After correctly noting the incompatibility between fixed exchange rates and internal price stability, Friedman contradicts himself by asserting that, in seeking to stabilize their internal price levels, Strong and Moreau violated the gold-standard “rules,” as if it were rules, not arbitrage, that constrain national price to converge toward a common level under a gold standard.

Friedman’s assertion that, after 1925, the dollar was undervalued and sterling overvalued was not wrong. But he misunderstood the consequences of currency undervaluation and overvaluation under the gold standard, a confusion stemming from the underlying misconception, derived from PSFM, that foreign exchange rates adjust to balance trade flows, so that, in equilibrium, no country runs a trade deficit or trade surplus.

Thus, in Friedman’s view, dollar undervaluation and sterling overvaluation implied a US trade surplus and British trade deficit, causing gold to flow from Britain to the US. Under gold-standard “rules,” the US money stock and US prices were supposed to rise and the British money stock and British prices were supposed to fall until undervaluation and overvaluation were eliminated. Friedman therefore blamed sterilization of gold inflows by the Fed for preventing the necessary increase in the US money stock and price level to restore equilibrium. But, in fact, from 1925 through 1928, prices in the US were roughly stable and prices in Britain fell slightly. Violating gold-standard “rules” did not prevent the US and British price levels from converging, a convergence driven by market forces, not “rules.”

The stance of monetary policy in a gold-standard country had minimal effect on either the quantity of money or the price level in that country, which were mainly determined by the internationally determined value of gold. What the stance of national monetary policy determines under the gold standard is whether the quantity of money in the country adjusts to the quantity demanded by a process of domestic monetary creation or withdrawal or by the inflow or outflow of gold. Sufficiently tight domestic monetary policy restricting the quantify of domestic money causes a compensatory gold inflow increasing the domestic money stock, while sufficiently easy money causes a compensatory outflow of gold reducing the domestic money stock. Tightness or ease of domestic monetary policy under the gold standard mainly affected gold and foreign-exchange reserves, and, only minimally, the quantity of domestic money and the domestic price level.

However, the combined effects of many countries simultaneously tightening monetary policy in a deliberate, or even inadvertent, attempt to accumulate — or at least prevent the loss — of gold reserves could indeed drive up the international value of gold through a deflationary process affecting prices in all gold-standard countries. Friedman, even while admitting that, in his Monetary History, he had understated the effect of the Bank of France on the Great Depression, referred only the overvaluation of sterling and undervaluation of the dollar and franc as causes of the Great Depression, remaining oblivious to the deflationary effects of gold accumulation and appreciation.

It was thus nonsensical for Friedman to argue that the mistake of the Bank of France during the Great Depression was not to increase the quantity of francs in proportion to the increase of its gold reserves. The problem was not that the quantity of francs was too low; it was that the Bank of France prevented the French public from collectively increasing the quantity of francs that they held except by importing gold.

Unlike Friedman, F. A. Hayek actually defended the policy of the Bank of France, and denied that the Bank of France had violated “the rules of the game” after nearly quadrupling its gold reserves between 1928 and 1932. Under his interpretation of those “rules,” because the Bank of France increased the quantity of banknotes after the 1928 restoration of convertibility by about as much as its gold reserves increased, it had fully complied with the “rules.” Hayek’s defense was incoherent; under its legal obligation to convert gold into francs at the official conversion rate, the Bank of France had no choice but to increase the quantity of francs by as much as its gold reserves increased.

That eminent economists like Hayek and Friedman could defend, or criticize, the conduct of the Bank of France during the Great Depression, because the Bank either did, or did not, follow “the rules of the game” under which the gold standard operated, shows the uselessness and irrelevance of the “rules of the game” as a guide to policy. For that reason alone, the failure of empirical studies to find evidence that “the rules of the game” were followed during the heyday of the gold standard is unsurprising. But the deeper reason for that lack of evidence is that PSFM, whose implementation “the rules of the game” were supposed to guarantee, was based on a misunderstanding of the international-adjustment mechanism under either the gold standard or any fixed-exchange-rates system.

Despite the grip of PSFM over most of the profession, a few economists did show a deeper understanding of the adjustment mechanism. The idea that the price level in terms of gold directly constrained the movements of national price levels across countries was indeed recognized by writers as diverse as Keynes, Mises, and Hawtrey who all pointed out that the prices of internationally traded commodities were constrained by arbitrage and that the free movement of capital across countries would limit discrepancies in interest rates across countries attached to the gold standard, observations that had already been made by Smith, Thornton, Ricardo, Fullarton and Mill in the classical period. But, until the Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments became popular in the 1970s, only Hawtrey consistently and systematically deduced the implications of those insights in analyzing both the Great Depression and the Bretton Woods system of fixed, but adjustable, exchange rates following World War II.

The inconsistencies and internal contradictions of PSFM were sometimes recognized, but usually overlooked, by business-cycle theorists when focusing on the disturbing influence of central banks, perpetuating mistakes of the Humean Currency School doctrine that attributed cyclical disturbances to the misbehavior of local banking systems that were inherently disposed to overissue their liabilities.