The week before last, Noah Smith wrote a post “The Neo-Fisherite Rebellion” discussing, rather sympathetically I thought, the contrarian school of monetary thought emerging from the Great American Heartland, according to which, notwithstanding everything monetary economists since Henry Thornton have taught, high interest rates are inflationary and low interest rates deflationary. This view of the relationship between interest rates and inflation was advanced (but later retracted) by Narayana Kocherlakota, President of the Minneapolis Fed in a 2010 lecture, and was embraced and expounded with increased steadfastness by Stephen Williamson of Washington University in St. Louis and the St. Louis Fed in at least one working paper and in a series of posts over the past five or six months (e.g. here, here and here). And John Cochrane of the University of Chicago has picked up on the idea as well in two recent blog posts (here and here). Others seem to be joining the upstart school as well.

The new argument seems simple: given the Fisher equation, in which the nominal interest rate equals the real interest rate plus the (expected) rate of inflation, a central bank can meet its inflation target by setting a fixed nominal interest rate target consistent with its inflation target and keeping it there. Once the central bank sets its target, the long-run neutrality of money, implying that the real interest rate is independent of the nominal targets set by the central bank, ensures that inflation expectations must converge on rates consistent with the nominal interest rate target and the independently determined real interest rate (i.e., the real yield curve), so that the actual and expected rates of inflation adjust to ensure that the Fisher equation is satisfied. If the promise of the central bank to maintain a particular nominal rate over time is believed, the promise will induce a rate of inflation consistent with the nominal interest-rate target and the exogenous real rate.

The novelty of this way of thinking about monetary policy is that monetary theorists have generally assumed that the actual adjustment of the price level or inflation rate depends on whether the target interest rate is greater or less than the real rate plus the expected rate. When the target rate is greater than the real rate plus expected inflation, inflation goes down, and when it is less than the real rate plus expected inflation, inflation goes up. In the conventional treatment, the expected rate of inflation is momentarily fixed, and the (expected) real rate variable. In the Neo-Fisherite school, the (expected) real rate is fixed, and the expected inflation rate is variable. (Just as an aside, I would observe that the idea that expectations about the real rate of interest and the inflation rate cannot occur simultaneously in the short run is not derived from the limited cognitive capacity of economic agents; it can only be derived from the limited intellectual capacity of economic theorists.)

The heretical views expressed by Williamson and Cochrane and earlier by Kocherlakota have understandably elicited scorn and derision from conventional monetary theorists, whether Keynesian, New Keynesian, Monetarist or Market Monetarist. (Williamson having appropriated for himself the New Monetarist label, I regrettably could not preserve an appropriate symmetry in my list of labels for monetary theorists.) As a matter of fact, I wrote a post last December challenging Williamson’s reasoning in arguing that QE had caused a decline in inflation, though in his initial foray into uncharted territory, Williamson was actually making a narrower argument than the more general thesis that he has more recently expounded.

Although deep down, I have no great sympathy for Williamson’s argument, the counterarguments I have seen leave me feeling a bit, shall we say, underwhelmed. That’s not to say that I am becoming a convert to New Monetarism, but I am feeling that we have reached a point at which certain underlying gaps in monetary theory can’t be concealed any longer. To explain what I mean by that remark, let me start by reviewing the historical context in which the ruling doctrine governing central-bank operations via adjustments in the central-bank lending rate evolved. The primary (though historically not the first) source of the doctrine is Henry Thornton in his classic volume The Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain.

Even though Thornton focused on the policy of the Bank of England during the Napoleonic Wars, when Bank of England notes, not gold, were legal tender, his discussion was still in the context of a monetary system in which paper money was generally convertible into either gold or silver. Inconvertible banknotes – aka fiat money — were the exception not the rule. Gold and silver were what Nick Rowe would call alpha money. All other moneys were evaluated in terms of gold and silver, not in terms of a general price level (not yet a widely accepted concept). Even though Bank of England notes became an alternative alpha money during the restriction period of inconvertibility, that situation was generally viewed as temporary, the restoration of convertibility being expected after the war. The value of the paper pound was tracked by the sterling price of gold on the Hamburg exchange. Thus, Ricardo’s first published work was entitled The High Price of Bullion, in which he blamed the high sterling price of bullion at Hamburg on an overissue of banknotes by the Bank of England.

But to get back to Thornton, who was far more concerned with the mechanics of monetary policy than Ricardo, his great contribution was to show that the Bank of England could control the amount of lending (and money creation) by adjusting the interest rate charged to borrowers. If banknotes were depreciating relative to gold, the Bank of England could increase the value of their notes by raising the rate of interest charged on loans.

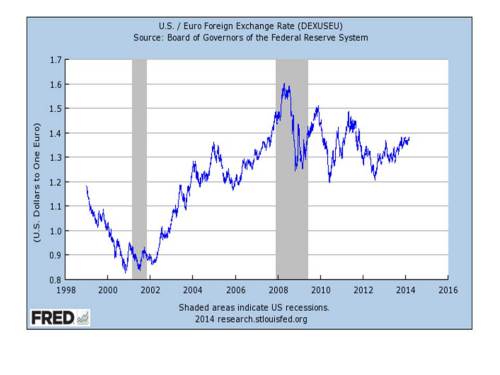

The point is that if you are a central banker and are trying to target the exchange rate of your currency with respect to an alpha currency, you can do so by adjusting the interest rate that you charge borrowers. Raising the interest rate will cause the exchange value of your currency to rise and reducing the interest rate will cause the exchange value to fall. And if you are operating under strict convertibility, so that you are committed to keep the exchange rate between your currency and an alpha currency at a specified par value, raising that interest rate will cause you to accumulate reserves payable in terms of the alpha currency, and reducing that interest rate will cause you to emit reserves payable in terms of the alpha currency.

So the idea that an increase in the central-bank interest rate tends to increase the exchange value of its currency, or, under a fixed-exchange rate regime, an increase in the foreign exchange reserves of the bank, has a history at least two centuries old, though the doctrine has not exactly been free of misunderstanding or confusion in the course of those two centuries. One of those misunderstandings was about the effect of a change in the central-bank interest rate, under a fixed-exchange rate regime. In fact, as long as the central bank is maintaining a fixed exchange rate between its currency and an alpha currency, changes in the central-bank interest rate don’t affect (at least as a first approximation) either the domestic money supply or the domestic price level; all that changes in the central-bank interest rate can accomplish is to change the bank’s holdings of alpha-currency reserves.

It seems to me that this long well-documented historical association between changes in the central-bank interest rates and the exchange value of currencies and the level of private spending is the basis for the widespread theoretical presumption that raising the central-bank interest rate target is deflationary and reducing it is inflationary. However, the old central-bank doctrine of the Bank Rate was conceived in a world in which gold and silver were the alpha moneys, and central banks – even central banks operating with inconvertible currencies – were beta banks, because the value of a central-bank currency was still reckoned, like the value of inconvertible Bank of England notes in the Napoleonic Wars, in terms of gold and silver.

In the Neo-Fisherite world, central banks rarely peg exchange rates against each other, and there is no longer any outside standard of value to which central banks even nominally commit themselves. In a world without the metallic standard of value in which the conventional theory of central banking developed, do the propositions about the effects of central-bank interest-rate setting still obtain? I am not so sure that they do, not with the analytical tools that we normally deploy when thinking about the effects of central-bank policies. Why not? Because, in a Neo-Fisherite world in which all central banks are alpha banks, I am not so sure that we really know what determines the value of this thing called fiat money. And if we don’t really know what determines the value of a fiat money, how can we really be sure that interest-rate policy works the same way in a Neo-Fisherite world that it used to work when the value of money was determined in relation to a metallic standard? (Just to avoid misunderstanding, I am not – repeat NOT — arguing for restoring the gold standard.)

Why do I say that we don’t know what determines the value of fiat money in a Neo-Fisherite world? Well, consider this. Almost three weeks ago I wrote a post in which I suggested that Bitcoins could be a massive bubble. My explanation for why Bitcoins could be a bubble is that they provide no real (i.e., non-monetary) service, so that their value is totally contingent on, and derived from (or so it seems to me, though I admit that my understanding of Bitcoins is partial and imperfect), the expectation of a positive future resale value. However, it seems certain that the resale value of Bitcoins must eventually fall to zero, so that backward induction implies that Bitcoins, inasmuch as they provide no real service, cannot retain a positive value in the present. On this reasoning, any observed value of a Bitcoin seems inexplicable except as an irrational bubble phenomenon.

Most of the comments I received about that post challenged the relevance of the backward-induction argument. The challenges were mainly of two types: a) the end state, when everyone will certainly stop accepting a Bitcoin in exchange, is very, very far into the future and its date is unknown, and b) the backward-induction argument applies equally to every fiat currency, so my own reasoning, according to my critics, implies that the value of every fiat currency is just as much a bubble phenomenon as the value of a Bitcoin.

My response to the first objection is that even if the strict logic of the backward-induction argument is inconclusive, because of the long and uncertain duration of the time elapse between now and the end state, the argument nevertheless suggests that the value of a Bitcoin is potentially very unsteady and vulnerable to sudden collapse. Those are not generally thought to be desirable attributes in a medium of exchange.

My response to the second objection is that fiat currencies are actually quite different from Bitcoins, because fiat currencies are accepted by governments in discharging the tax liabilities due to them. The discharge of a tax liability is a real (i.e. non-monetary) service, creating a distinct non-monetary demand for fiat currencies, thereby ensuring that fiat currencies retain value, even apart from being accepted as a medium of exchange.

That, at any rate, is my view, which I first heard from Earl Thompson (see his unpublished paper, “A Reformulation of Macroeconomic Theory” pp. 23-25 for a derivation of the value of fiat money when tax liability is a fixed proportion of income). Some other pretty good economists have also held that view, like Abba Lerner, P. H. Wicksteed, and Adam Smith. Georg Friedrich Knapp also held that view, and, in his day, he was certainly well known, but I am unable to pass judgment on whether he was or wasn’t a good economist. But I do know that his views about money were famously misrepresented and caricatured by Ludwig von Mises. However, there are other good economists (Hal Varian for one), apparently unaware of, or untroubled by, the backward induction argument, who don’t think that acceptability in discharging tax liability is required to explain the value of fiat money.

Nor do I think that Thompson’s tax-acceptability theory of the value of money can stand entirely on its own, because it implies a kind of saw-tooth time profile of the price level, so that a fiat currency, earning no liquidity premium, would actually be appreciating between peak tax collection dates, and depreciating immediately following those dates, a pattern not obviously consistent with observed price data, though I do recall that Thompson used to claim that there is a lot of evidence that prices fall just before peak tax-collection dates. I don’t think that anyone has ever tried to combine the tax-acceptability theory with the empirical premise that currency (or base money) does in fact provide significant liquidity services. That, it seems to me, would be a worthwhile endeavor for any eager young researcher to undertake.

What does all of this have to do with the Neo-Fisherite Rebellion? Well, if we don’t have a satisfactory theory of the value of fiat money at hand, which is what another very smart economist Fischer Black – who, to my knowledge never mentioned the tax-liability theory — thought, then the only explanation of the value of fiat money is that, like the value of a Bitcoin, it is whatever people expect it to be. And the rate of inflation is equally inexplicable, being just whatever it is expected to be. So in a Neo-Fisherite world, if the central bank announces that it is reducing its interest-rate target, the effect of the announcement depends entirely on what “the market” reads into the announcement. And that is exactly what Fischer Black believed. See his paper “Active and Passive Monetary Policy in a Neoclassical Model.”

I don’t say that Williamson and his Neo-Fisherite colleagues are correct. Nor have they, to my knowledge, related their arguments to Fischer Black’s work. What I do say (indeed this is a problem I raised almost three years ago in one of my first posts on this blog) is that existing monetary theories of the price level are unable to rule out his result, because the behavior of the price level and inflation seems to depend, more than anything else, on expectations. And it is far from clear to me that there are any fundamentals in which these expectations can be grounded. If you impose the rational expectations assumption, which is almost certainly wrong empirically, maybe you can argue that the central bank provides a focal point for expectations to converge on. The problem, of course, is that in the real world, expectations are all over the place, there being no fundamentals to force the convergence of expectations to a stable equilibrium value.

In other words, it’s just a mess, a bloody mess, and I do not like it, not one little bit.