In my talk last week at the Mercatus Conference on Monetary Rules for a Post-Crisis World, I discussed how monetary rules and the thinking about monetary rules have developed over time. The point that I started with was that monetary rules become necessary only when the medium of exchange has a value that exceeds the cost of producing the medium of exchange. You don’t need a monetary rule if money is a commodity; people just trade stuff for stuff; it’s not barter, because everyone accepts one real commodity, making that commodity the medium of exchange. But there’s no special rule governing the monetary system beyond the rules that govern all forms of exchange. the first monetary rule came along only when something worth more than its cost of production was used as money. This might have happened when people accepted minted coins at face value, even though the coins were not full-bodied. But that situation was not a stable equilibrium, because eventually Gresham’s Law kicks in, and the bad money drives out the good, so that the value of coins drops to their metallic value rather than their face value. So no real monetary rule was operating to control the value of coinage in situations where the coinage was debased.

So the idea of an actual monetary rule to govern the operation of a monetary system only emerged when banks started to issue banknotes. Banknotes having a negligible cost of production, a value in excess of that negligible cost could be imparted to those essentially worthless banknotes only by banks undertaking a commitment — a legally binding obligation — to make those banknotes redeemable (convertible) for a fixed weight of gold or silver or some other valuable material whose supply was not under the control of the bank itself. This convertibility commitment can be thought of as a kind of rule, but convertibility was not originally undertaken as a policy rule; it was undertaken simply as a business expedient; it was the means by which banks could create a demand for the banknotes that they wanted to issue to borrowers so that they could engage in the profitable business of financial intermediation.

It was in 1797, during the early stages of the British-French wars after the French Revolution, when, the rumor of a French invasion having led to a run on Bank of England notes, the British government prohibited the Bank of England from redeeming its banknotes for gold, and made banknotes issued by the Bank of England legal tender. The subsequent premium on gold in Continental commodity markets in terms of sterling – what was called the high price of bullion – led to a series of debates which engaged some of the finest economic minds in Great Britain – notably David Ricardo and Henry Thornton – over the causes and consequences of the high price of bullion and, if a remedy was in fact required, the appropriate policy steps to be taken to administer that remedy.

There is a vast literature on the many-sided Bullionist debates as they are now called, but my only concern here is with the final outcome of the debates, which was the appointment of a Parliamentary Commission, which included none other than the great Henry Thornton, himself, and two less renowned colleagues, William Huskisson and Francis Horner, who collaborated to write a report published in 1811 recommending the speedy restoration of convertibility of Bank of England notes. The British government and Parliament were unwilling to follow the recommendation while war with France was ongoing, however, there was a broad consensus in favor of the restoration of convertibility once the war was over.

After Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815, the process of restoring convertibility was begun with the intention of restoring the pre-1797 conversion rate between banknotes and gold. Parliament in fact enacted a statute defining the pound sterling as a fixed weight of gold. By 1819, the value of sterling had risen to its prewar level, and in 1821 the legal obligation of the Bank of England to convert its notes into gold was reinstituted. So the first self-consciously adopted monetary rule was the Parliamentary decision to restore the convertibility of banknotes issued by the Bank of England into a fixed weight of gold.

However, the widely held expectations that the restoration of convertibility of banknotes issued by the Bank of England into gold would produce a stable monetary regime and a stable economy were quickly disappointed, financial crises and depressions occurring in 1825 and again in 1836. To explain the occurrence of these unexpected financial crises and periods of severe economic distress, a group of monetary theorists advanced a theory based on David Hume’s discussion of the price-specie-flow mechanism in his essay “Of the Balance of Trade,” in which he explained the automatic tendency toward equilibrium in the balance of trade and stocks of gold and precious metals among nations. Hume carried out his argument in terms of a fully metallic (gold) currency, and, in other works, Hume decried the tendency of banks to issue banknotes to excess, thereby causing inflation and economic disturbances.

So the conclusion drawn by these monetary theorists was that the Humean adjustment process would work smoothly only if gold shipments into Britain or out of Britain would result in a reduction or increase in the quantity of banknotes exactly equal to the amount of gold flowing into or out of Britain. It was the failure of the Bank of England and the other British banks to follow the Currency Principle – the idea that the total amount of currency in the country should change by exactly the same amount as the total quantity of gold reserves in the country – that had caused the economic crises and disturbances marking the two decades since the resumption of convertibility in 1821.

Those advancing this theory of economic fluctuations and financial crises were known as the Currency School and they succeeded in persuading Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister to support legislation to require the Bank of England and the other British Banks to abide by the Currency Principle. This was done by capping the note issue of all banks other than the Bank of England at existing levels and allowing the Bank of England to increase its issue of banknotes only upon deposit of a corresponding quantity of gold bullion. The result was in effect to impose a 100% marginal reserve requirement on the entire British banking system. Opposition to the Currency School largely emanated from what came to be known as the Banking School, whose most profound theorist was John Fullarton who formulated the law of reflux, which focused attention on the endogenous nature of the issue of banknotes by commercial banks. According to Fullarton and the Banking School, the issue of banknotes by the banking system was not a destabilizing and disequilibrating disturbance, but a response to the liquidity demands of traders and dealers. Once these liquidity demands were satisfied, the excess banknotes, returning to the banks in the ordinary course of business, would be retired from circulation unless there was a further demand for liquidity from some other source.

The Humean analysis, abstracting from any notion of a demand for liquidity, was therefore no guide to the appropriate behavior of the quantity of banknotes. Imposing a 100% marginal reserve requirement on the supply of banknotes would make it costly for traders and dealers to satisfy their demands for liquidity in times of financial stress; rather than eliminate monetary disturbances, the statutory enactment of the Currency Principle would be an added source of financial disturbance and disorder.

With the support of Robert Peel and his government, the arguments of the Currency School prevailed, and the Bank Charter Act was enacted in 1844. In 1847, despite the hopes of its supporters that an era of financial tranquility would follow, a new financial crisis occurred, and the crisis was not quelled until the government suspended the Bank Charter Act, thereby enabling the Bank of England to lend to dealers and traders to satisfy their demands for liquidity. Again in 1857 and in 1866, crises occurred which could not be brought under control before the government suspended the Bank Charter Act.

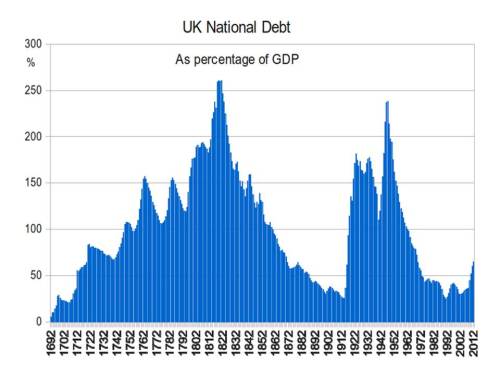

So British monetary history in the first half of the nineteenth century provides us with two paradigms of monetary rules. The first is a price rule in which the value of a monetary instrument is maintained at a level above its cost of production by way of a convertibility commitment. Given the convertibility commitment, the actual quantity of the monetary instrument that is issued is whatever quantity the public wishes to hold. That, at any rate, was the theory of the gold standard. There were – and are – at least two basic problems with that theory. First, making the value of money equal to the value of gold does not imply that the value of money will be stable unless the value of gold is stable, and there is no necessary reason why the value of gold should be stable. Second, the behavior of a banking system may be such that the banking system will itself destabilize the value of gold, e.g., in periods of distress when the public loses confidence in the solvency of banks and banks simultaneously increase their demands for gold. The resulting increase in the monetary demand for gold drives up the value of gold, triggering a vicious cycle in which the attempt by each to increase his own liquidity impairs the solvency of all.

The second rule is a quantity rule in which the gold standard is forced to operate in a way that prevents the money supply from adjusting freely to variations in the demand for money. Such a rule makes sense only if one ignores or denies the possibility that the demand for money can change suddenly and unpredictably. The quantity rule is neither necessary nor sufficient for the gold standard or any monetary standard to operate. In fact, it is an implicit assertion that the gold standard or any metallic standard cannot operate, the operation of profit-seeking private banks and their creation of banknotes and deposits being inconsistent with the maintenance of a gold standard. But this is really a demand for abolition of the gold standard in which banknotes and deposits draw their value from a convertibility commitment and its replacement by a pure gold currency in which there is no distinction between gold and banknotes or deposits, banknotes and deposits being nothing more than a receipt for an equivalent physical amount of gold held in reserve. That is the monetary system that the Currency School aimed at achieving. However, imposing the 100% reserve requirement only on banknotes, they left deposits unconstrained, thereby paving the way for a gradual revolution in the banking practices of Great Britain between 1844 and about 1870, so that by 1870 the bulk of cash held in Great Britain was held in the form of deposits not banknotes and the bulk of business transactions in Britain were carried out by check not banknotes.

So Milton Friedman was working entirely within the Currency School monetary tradition, formulating a monetary rule in terms of a fixed quantity rather than a fixed price. And, in ultimately rejecting the gold standard, Friedman was merely following the logic of the Currency School to its logical conclusion, because what ultimately matters is the quantity rule not the price rule. For the Currency School, the price rule was redundant, a fifth wheel; the real work was done by the 100% marginal reserve requirement. Friedman therefore saw the gold standard as an unnecessary and even dangerous distraction from the ultimate goal of keeping the quantity of money under strict legal control.

It is in the larger context of Friedman’s position on 100% reserve banking, of which he remained an advocate until he shifted to the k-percent rule in the early 1960s, that his anomalous description of the classical gold standard of late nineteenth century till World War I as a pseudo-gold standard can be understood. What Friedman described as a real gold standard was a system in which only physical gold and banknotes and deposits representing corresponding holdings of physical gold circulate as media of exchange. But this is not a gold standard that has ever existed, so what Friedman called a real gold standard was actually just the gold standard of his hyperactive imagination.