While searching for material on the close and multi-faceted relationship between Keynes and Hawtrey which I am now studying and writing about, I came across a remarkable juxtaposition of two reviews in the British economics journal Economica, published by the London School of Economics. Economica was, after the Economic Journal published at Cambridge (and edited for many years by Keynes), probably the most important economics journal published in Britain in the early 1930s. Having just arrived in Britain in 1931 to a spectacularly successful debut with his four lectures at LSE, which were soon published as Prices and Production, and having accepted the offer of a professorship at LSE, Hayek began an intense period of teaching and publishing, almost immediately becoming the chief rival of Keynes. The rivalry had been more or less officially inaugurated when Hayek published the first of his two-part review-essay of Keynes’s recently published Treatise on Money in the August 1931 issue of Economica, followed by Keynes’s ill-tempered reply and Hayek’s rejoinder in the November 1931 issue, with the second part of Hayek’s review appearing in the February 1932 issue.

But interestingly in the same February issue containing the second installment of Hayek’s lengthy review essay, Hayek also published a short (2 pages, 3 paragraphs) review of Hawtrey’s Trade Depression and the Way Out immediately following Hawtrey’s review of Hayek’s Prices and Production in the same issue. So not only was Hayek engaging in controversy with Keynes, he was arguing with Hawtrey as well. The points at issue were similar in the two exchanges, but there may well be more to learn from the lower-key, less polemical, exchange between Hayek and Hawtrey than from the overheated exchange between Hayek and Keynes.

So here is my summary (in reverse order) of the two reviews:

Hayek on Trade Depression and the Way Out.

Hayek, in his usual polite fashion, begins by praising Hawtrey’s theoretical eminence and skill as a clear expositor of his position. (“the rare clarity and painstaking precision of his theoretical exposition and his very exceptional knowledge of facts making anything that comes from his pen well worth reading.”) However, noting that Hawtrey’s book was aimed at a popular rather than a professional audience, Hayek accuses Hawtrey of oversimplification in attributing the depression to a lack of monetary stimulus.

Hayek proceeds in his second paragraph to explain what he means by oversimplification. Hayek agrees that the origin of the depression was monetary, but he disputes Hawtrey’s belief that the deflationary shocks were crucial.

[Hawtrey’s] insistence upon the relation between “consumers’ income” and “consumers’ outlay” as the only relevant factor prevents him from seeing the highly important effects of monetary causes upon the capitalistic structure of production and leads him along the paths of the “purchasing power theorists” who see the source of all evil in the insufficiency of demand for consumers goods. . . . Against all empirical evidence, he insists that “the first symptom of contracting demand is a decline in sales to the consumer or final purchaser.” In fact, of course, depression has always begun with a decline in demand, not for consumers’ goods but for capital goods, and the one marked phenomenon of the present depression was that the demand for consumers’ goods was very well maintained for a long while after the crisis occurred.

Hayek’s comment seems to me to misinterpret Hawtrey slightly. Hawtrey wrote “a decline in sales to the consumer or final purchaser,” which could refer to a decline in the sales of capital equipment as well as the sales of consumption goods, so Hawtrey’s assertion was not necessarily inconsistent with Hayek’s representation about the stability of consumption expenditure immediately following a cyclical downturn. It would also not be hard to modify Hawtrey’s statement slightly; in an accelerator model, with which Hawtrey was certainly familiar, investment depends on the growth of consumption expenditures, so that a leveling off of consumption, rather than an actual downturn in consumption, would suffice to trigger the downturn in investment which, according to Hayek, was a generally accepted stylized fact characterizing the cyclical downturn.

Hayek continues:

[W]hat Mr. Hawtrey, in common with many other English economists [I wonder whom Hayek could be thinking of], lacks is an adequate basic theory of the factors which affect [the] capitalistic structure of production.

Because of Hawtrey’s preoccupation with the movements of the overall price level, Hayek accuses Hawtrey of attributing the depression solely “to a process of deflation” for which the remedy is credit expansion by the central banks. [Sound familiar?]

[Hawtrey] seems to extend [blame for the depression] on the policy of the Bank of England even to the period before 1929, though according to his own criterion – the rise in the prices of the original factors of production [i.e., wages] – it is clear that, in that period, the trouble was too much credit expansion. “In 1929,” Mr. Hawtrey writes, “when productive activity was at its highest in the United States, wages were 120 percent higher than in 1913, while commodity prices were only 50 percent higher.” Even if we take into account the fact that the greater part of this rise in wages took place before 1921, it is clear that we had much more credit expansion before 1929 than would have been necessary to maintain the world-wage-level. It is not difficult to imagine what would have been the consequences if, during that period, the Bank of England had followed Mr. Hawtrey’s advice and had shown still less reluctance to let go. But perhaps, this would have exposed the dangers of such frankly inflationist advice quicker than will now be the case.

A remarkable passage indeed! To accuse Hawtrey of toleration of inflation, he insinuates that the 50% rise in wages from 1913 to 1929, was at least in part attributable to the inflationary policies Hawtrey was advocating. In fact, I believe that it is clear, though I don’t have easy access to the best data source C. H. Feinstein’s “Changes in Nominal Wages, the Cost of Living, and Real Wages in the United Kingdom over Two Centuries, 1780-1990,” in Labour’s Reward edited by P. Schoillers and V. Zamagni (1995). From 1922 to 1929 the overall trend of nominal wages in Britain was actually negative. Hayek’s reference to “frankly inflationist advice” was not just wrong, but wrong-headed.

Hawtrey on Prices and Production

Hawtrey spends the first two or three pages or so of his review giving a summary of Hayek’s theory, explaining the underlying connection between Hayek and the Bohm-Bawerkian theory of production as a process in time, with the length of time from beginning to end of the production process being a function of the rate of interest. Thus, reducing the rate of interest leads to a lengthening of the production process (average period of production). Credit expansion financed by bank lending is the key cyclical variable, lengthening the period of production, but only temporarily.

The lengthening of the period of production can only take place as long as inflation is increasing, but inflation cannot increase indefinitely. When inflation stops increasing, the period of production starts to contract. Hawtrey explains:

Some intermediate products (“non-specific”) can readily be transferred from one process to another, but others (“specific”) cannot. These latter will no longer be needed. Those who have been using them, and still more those who have producing them, will be thrown out of employment. And here is the “explanation of how it comes about at certain times that some of the existing resources cannot be used.” . . .

The originating cause of the disturbance would therefore be the artificially enhanced demand for producers’ goods arising when the creation of credit in favour of producers supplements the normal flow savings out of income. It is only because the latter cannot last for ever that the reaction which results in under-employment occurs.

But Hawtrey observes that only a small part of the annual capital outlay is applied to lengthening the period of production, capital outlay being devoted mostly to increasing output within the existing period of production, or to enhancing productivity through the addition of new plant and equipment embodying technical progress and new inventions. Thus, most capital spending, even when financed by credit creation, is not associated with any alteration in the period of production. Hawtrey would later introduce the terms capital widening and capital deepening to describe investments that do not affect the period of production and those that do affect it. Nor, in general, are capital-deepening investments the most likely to be adopted in response to a change in the rate of interest.

Similarly, If the rate of interest were to rise, making the most roundabout processes unprofitable, it does not follow that such processes will have to be scrapped.

A piece of equipment may have been installed, of which the yield, in terms of labour saved, is 4 percent on its cost. If the market rate of interest rises to 5 percent, it would no longer be profitable to install a similar piece. But that does not mean that, once installed, it will be left idle. The yield of 4 percent is better than nothing. . . .

When the scrapping of plant is hastened on account of the discovery of some technically improved process, there is a loss not only of interest but of the residue of depreciation allowance that would otherwise have accumulated during its life of usefulness. It is only when the new process promises a very suitable gain in efficiency that premature scrapping is worthwhile. A mere rise in the rate of interest could never have that effect.

But though a rise in the rate of interest is not likely to cause the scrapping of plant, it may prevent the installation of new plant of the kind affected. Those who produce such plant would be thrown out of employment, and it is this effect which is, I think, the main part of Dr. Hayek’s explanation of trade depressions.

But what is the possible magnitude of the effect? The transition from activity to depression is accompanied by a rise in the rate of interest. But the rise in the long-term rate is very slight, and moreover, once depression has set in, the long-term rate is usually lower than ever.

Changes are in any case perpetually occurring in the character of the plant and instrumental goods produced for use in industry. Such changes are apt to throw out of employment any highly specialized capital and labour engaged in the production of plant which becomes obsolete. But among the causes of obsolescence a rise in the rate of interest is certainly one of the least important and over short periods it may safely be said to be quite negligible.

Hawtrey goes on to question Hayek’s implicit assumption that the effects of the depression were an inevitable result of stopping the expansion of credit, an assumption that Hayek disavowed much later, but it was not unreasonable for Hawtrey to challenge Hayek on this point.

It is remarkable that Dr. Hayek does not entertain the possibility of a contraction of credit; he is content to deal with the cessation of further expansion. He maintains that at a time of depression a credit expansion cannot provide a remedy, because if the proportion between the demand for consumers’ goods and the demand for producers’ goods “is distorted by the creation of artificial demand, it must mean that part of the available resources is again led into a wrong direction and a definite and lasting adjustment is again postponed.” But if credit being contracted, the proportion is being distorted by an artificial restriction of demand.

The expansion of credit is assumed to start by chance, or at any rate no cause is suggested. It is maintained because the rise of prices offers temporary extra profits to entrepreneurs. A contraction of credit might equally well be assumed to start, and then to be maintained because the fall of prices inflicts temporary losses on entrepreneurs, and deters them from borrowing. Is not this to be corrected by credit expansion?

Dr. Hayek recognizes no cause of under-employment of the factors of production except a change in the structure of production, a “shortening of the period.” He does not consider the possibility that if, through a credit contraction or for any other reason, less money altogether is spent on intermediate products (capital goods), the factors of production engaged in producing these products will be under-employed.

Hawtrey then discusses the tension between Hayek’s recognition that the sense in which the quantity of money should be kept constant is the maintenance of a constant stream of money expenditure, so that in fact an ideal monetary policy would adjust the quantity of money to compensate for changes in velocity. Nevertheless, Hayek did not feel that it was within the capacity of monetary policy to adjust the quantity of money in such a way as to keep total monetary expenditure constant over the course of the business cycle.

Here are the concluding two paragraphs of Hawtrey’s review:

In conclusion, I feel bound to say that Dr. Hayek has spoiled an original piece of work which might have been an important contribution to monetary theory, by entangling his argument with the intolerably cumbersome theory of capital derived from Jevons and Bohm-Bawerk. This theory, when it was enunciated, was a noteworthy new departure in the metaphysics of political economy. But it is singularly ill-adapted for use in monetary theory, or indeed in any practical treatment of the capital market.

The result has been to make Dr. Hayek’s work so difficult and obscure that it is impossible to understand his little book of 112 pages except at the cost of many hours of hard work. And at the end we are left with the impression, not only that this is not a necessary consequence of the difficulty of the subject, but that he himself has been led by so ill-chosen a method of analysis to conclusions which he would hardly have accepted if given a more straightforward form of expression.

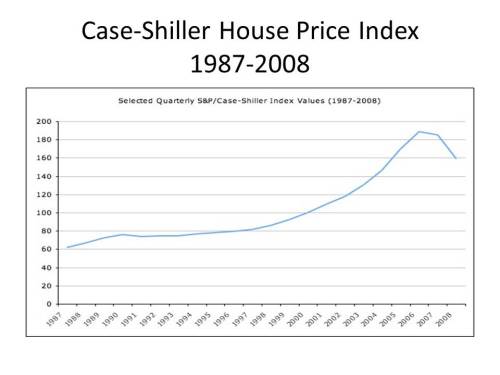

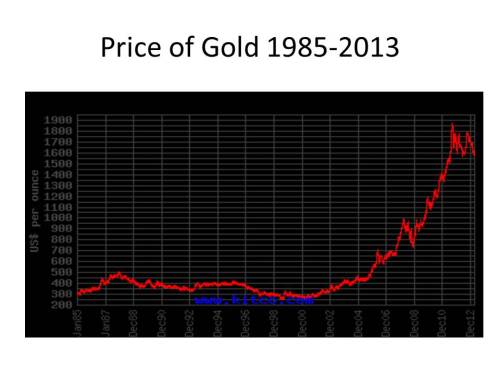

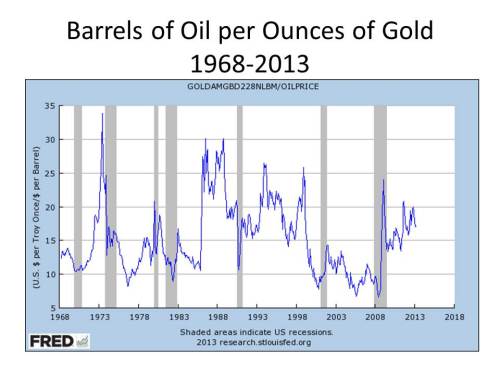

Do Mr. Tamny and his buddies at the Wall Street Journal really expect people to buy this nonsense? This is what happens to your brain when you are obsessed with gold. If you think that the US and the world economies have been on a wild ride these past five years, imagine what it would have been like if the US or the world price level had been fluctuating as the relative price of gold in terms of oil has been fluctuating over the same time period. And don’t even think about what would have happened over the past 45 years under Mr. Tamny’s ideal, constant, gold-based monetary standard.

Do Mr. Tamny and his buddies at the Wall Street Journal really expect people to buy this nonsense? This is what happens to your brain when you are obsessed with gold. If you think that the US and the world economies have been on a wild ride these past five years, imagine what it would have been like if the US or the world price level had been fluctuating as the relative price of gold in terms of oil has been fluctuating over the same time period. And don’t even think about what would have happened over the past 45 years under Mr. Tamny’s ideal, constant, gold-based monetary standard.