J. R. Hicks, who introduced the concept of intertemporal equilibrium to English-speaking economists in Value and Capital, was an admirer of Carl Menger, one of the three original Marginal Revolutionaries, crediting Menger in particular for having created an economic theory in time (see his “Time in Economics” in Collected Essays on Economic Theory, vol. II). The goal of grounding economic theory in time inspired many of Hicks’s theoretical contributions, including his exposition of intertemporal equilibrium in Value and Capital which was based on the idea of temporary equilibrium.

Recognizing that (full) intertemporal equilibrium requires all current markets to clear and all agents to share correct expectations of the future prices on which their plans depend, Hicks used temporary equilibrium to describe a sequence of intermediate positions of an economy moving toward or away from (full) intertemporal equilibrium. This was done by positing discrete weekly time periods in which economic activity–production, consumption, buying and selling–occurs during the week at equilibrium prices, prices being set on Monday followed by economic activity at Monday’s prices until start of a new week. This modeling strategy allowed Hicks to embed a quasi-static supply and demand analysis within his intertemporal equilibrium model, the week serving as a time period short enough to allow a conditions, including agents’ expectations, to be plausibly held constant until the following week. Demarcating a short period in which conditions remain constant simplifies the analysis by allowing changes conditions to change once a week. A static weekly analysis is transformed into a dynamic analysis by way of goods and assets held from week to week and by recognizing that agents’ plans to buy and sell depend not only on current prices but on expected future prices.

Weekly price determination assumes that all desired purchases and sales, at Monday’s prices, can be executed, i.e., that markets clear. But market-clearing in temporary equilibrium, involves an ambiguity not present in static equilibrium in which agents’ decision depend only on current prices. Unlike a static model. in which changes in demand and supply are permanent, and no intertemporal substitution occurs, intertemporal substitution both in supply and in demand do occur in a temporary-equilibrium model, so that transitory changes in the demand for, and supply of, goods and assets held from week to week do occur. Distinguishing between desired and undesired (unplanned, involuntary) inventory changes is difficult without knowledge of agents’ plans and the expectations on which their plans depend. Because Monday prices may differ from the prices that agents had expected, some agents may be unable to execute their prior plans to buy and sell.

Some agents may make only minor plan adjustments; others may have to make significant adjustments, and some even scrapping plans that became unviable. The disappointment of expectations likely also causes some or all previously held expectations to be revised. The interaction between expected and realized prices in a temporary-equilibrium model clearly resembles how, according to Menger, the current values of higher-order goods are imputed from the expected prices of the lower-order goods into which those higher-order goods will be transformed.

Hicks never fully developed his temporary equilibrium method (See DeVroey, 2006, “The Temporary Equilibrium Method: Hicks against Hicks”), eventually replacing the market-clearing assumption of what he called a flex-price model for a fix-price disequilibrium model. Hicks had two objections to his temporary-equilibrium method: a) that changes in industrial organization, e.g., the vertical integration of large industrial firms into distribution and retailing, rendered flex-price models increasingly irrelevant to modern economies, and b) that in many markets (especially the labor market) a week is too short for the adjustments necessary for markets to clear. Hicks’s dissatisfaction with temporary equilibrium was reinforced by the apparent inconsistency between flex-price models and the Keynesian model to which, despite his criticisms, he remained attached.

DeVroey rejected Hicks’s second reason for dissatisfaction with his creation, showing it to involve a confusions between logical time (i.e., a sequence of temporal events of unspecified duration) and real time (i.e, the temporal duration of those events). The temporary-equilibrium model pertains to both logical and real time. The function of “Mondays” was to telescope flexible market-clearing price adjustments into a discrete logical time period wherein all the information relevant to price determination is brought to bear. Calling that period a “day” serves no purpose other than to impart the fictitious appearance of realism to an artifact. Whether price determination is telescoped into an instant or a day does not matter.

As for the first reason, DeVroey observed that Hicks’s judgment that flex-price models became irrelevant owing to changes in industrial organization are neither empirically compelling, the stickiness of some prices having always been recognized, nor theoretically necessary. The temporary equilibrium analysis was not meant to be a realistic description of price determination, but as a framework for understanding how a competitive economic system responds to displacements from equilibrium. Hicks seemed to conclude that the assumption of market-clearing rendered temporary-equilibrium models unable to account for high unemployment and other stylized facts related to macroeconomic cycles. But, as noted above, market-clearing in temporary equilibrium does preclude unplanned (aka involuntary) inventory accumulation and unplanned intertemporal labor substitution (aka involuntary unemployment).

Hicks’s seeming confusion about his own idea is hard to understand. In criticizing temporary equilibrium as an explanation of how a competitive economic system operates, he lost sight of the distinction that he had made between disequilibrium as markets failing to clear at a given time and disequilibrium as the absence of intertemporal equilibrium in which mutually consistent optimized plans can be executed by independent agents.

But beyond DeVroey’s criticisms of Hicks’s reasons for dissatisfaction with his temporary-equilibrium model, a more serious problem with Hicks’s own understanding of the temporary-equilibrium model is that he treated agents’ expectations as exogenous parameters within the model rather than as equilibrating variables. Here is how Hicks described the parametric nature of agents’ price expectations.

The effect of actual prices on price expectations is capable of further analysis; but even here we can give no simple rule. Even if autonomous variations are left out of account, there are still two things to consider: the influence of present prices and influence of past prices. These act in very different ways, and so it makes a great deal of difference which influence is the stronger.

Since past prices are past, they are, with respect to the current situation, simply data; if their influence is completely dominant, price-expectations can be treated as data too. This is the case we began by considering; the change in the current price does not disturb price-expectations, it is treated as quite temporary. But as soon as past prices cease to be completely dominant, we have to allow for some influence of current prices on expectations. Even so, that influence may have some various degrees of intensity, and work in various different ways.

It does not seem possible to carry general economic analysis of this matter any further; all we can do here is to list a number of possible cases. A list will be more useful if it is systematic; let us therefore introduce a measure for the reaction we are studying. If we neglect the possibility that a change in the current price of X may affect to a different extent the price of X expected to rule at different future dates, and if we also neglect the possibility that it may affect the expected future prices of other commodities or factors (both of which are serious omissions), then we may classify cases according to the elasticity of expectations. (Value and Capital. 2d ed., pp. 204-05).

When Hicks wrote Value and Capital, and for more than three decades thereafter, treating expectations as exogenous variables was routine, except when economists indulged the admittedly fanciful assumption of perfect foresight. It was not until the rational-expectations revolution that expectations came to be viewed as equilibrating. In almost all of Milton Friedman’s theorizing about expectations, for example, his assumption was that expectations are adaptive, Even in his famous explication of the natural-rate hypothesis, Friedman (1968: “The Role of Monetary Policy”) assumed that expectations are adaptive to prior experience, which corresponds to the elasticity of expectations being less than unity. Hicks failed to understand that expectations are formed endogenously by agents, not parametrically by the model, and that endogenous process may sometimes bring the system closer to, and sometimes further from, equilibrium.

Consider Hicks’s analysis of a change in the price of one commodity, given a fixed interest rate, an endogenous money supply and unit-elastic price expectations, .

Suppose that the rate of interest . . . is taken as given, while the price of one commodity (X) rises by 5 per cent. If the system is to be perfectly stable, this rise should induce an excess supply of X, however many . . . repercussions through other markets we allow for. Now what are the changes in prices which will restore equality between supply and demand in the markets for other commodities? If we consider some other markets only, we get results which do not differ very much from those to which we have been accustomed; the stability of the system survives these tests without difficulty. But when we consider the repercussions on all other markets . . . then we seem to move into a different world. Equilibrium can only be restored in the other commodity markets if the prices of the other commodities are unchanged, and the price ratios between all current prices and all expected prices are unchanged (since elasticities of expectations are unity), and (ex hypothesi) rates of interest are unchanged—then there is no opportunity for substitution anywhere. The demands and supplies for all goods and services will be unchanged. Being equal before, they will be equal still. It is a general proportional rise in prices which restores equilibrium in the other commodity markets; but it fails to produce an excess supply over demand in the market for the first commodity X. So far as the commodity markets taken alone are concerned, the system behaves like Wicksell’s system. It is in ‘neutral equilibrium’; that is to say, it can be in equilibrium at any level of money prices. [Hicks’s footnote here is as follows: The reader will have noticed that this argument depends upon the assumption that the system of relative prices is uniquely determined. I do not feel many qualms about this assumption myself. If it is not justified anything may happen.]

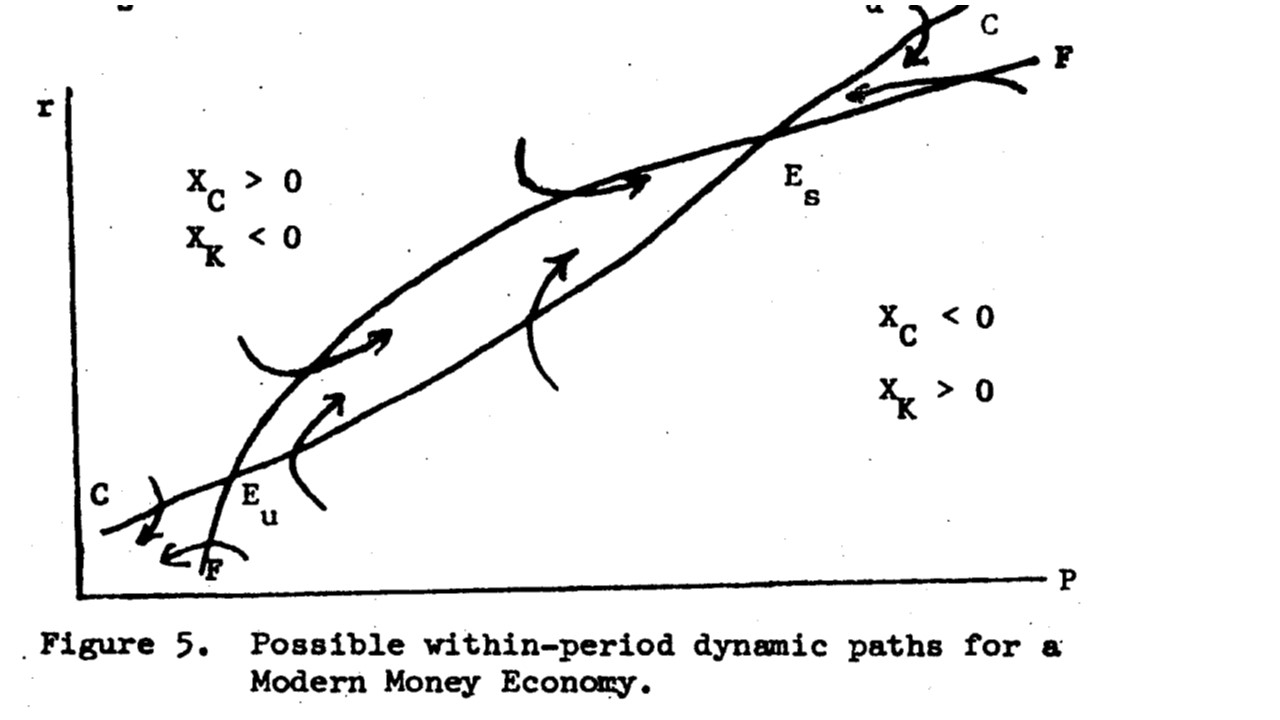

If elasticities of expectations are generally greater than unity, so that people interpret a change in prices, not merely as an indication that they will go on changing in the same direction, then a rise in all prices by so much per cent (with constant rate of interest) will make demands generally greater than supplies, so that the rise in prices will continue. A system with elasticities of expectations greater than unity, and constant rate of interest, is definitely unstable.

Technically, then, the case where elasticities of expectations ae equal to unity marks the dividing line between stability and instability. But its own stability is of a very questionable sort. A slight disturbance will be sufficient to make it pass over into instability.1 (Id., pp. 254-55).

Of course, to view price expectations as equilibrating variables does not imply that price expectations do equilibrate; it means that expectations adjust endogenously as agents obtain new information and that, if agents’ expectations are correct, intertemporal equilibrium will result. Current prices are also equilibrating variables, but, contrary to the rational-expectations postulate, expectations are only potentially, not necessarily, equilibrating. Whether expectations equilibrate or disequilibrate is an empirical question that does not admit of an a priori answer.

Hicks was correct that, owing to the variability of expectations, the outcomes of a temporary-equilibrium model are indeterminate and that unstable outcomes tend to follow from unstable expectations. What he did not do was identify the role of disappointed expectations in the coordination failures that cause severe macroeconomic downturns. Disappointed expectations likely lead to or coincide with monetary disturbances, but contrary to Clower (1965: “The Keynesian Counterrevolution: A Theoretical Appraisal”), monetary exchange is not the only, or even the primary, cause of disruptive expectational disappointments.

In the complex trading networks unerlying modern economies susceptible to macroeconomic disturbances, credit is an essential element of commercial relationships. Most commerce is conducted by way of credit; only small amounts of legal commerce is by immediate transfer of legal-tender cash or currency. In the imaginary world described by the ADM model, no credit is needed or used, because transactions are validated by the Walrasian auctioneer before trading starts.

But in the real world, trades are not validated in advance, agents relying instead on the credit-worthiness of counterparties. Establishing the creditworthiness of counterparties is costly, so specialists (financial intermediaries) emerge to guage traders’ creditworthiness. It is the possibility of expectational disappointment, which are excluded a priori from the ADM general-equilibrium model, that creates both a demand for, and a supply of, credit money, not vice versa. At times, this had been done directly, but it is overwhelmingly done by intermediaries whose credit worthiness is well and widely recognized. Intermediaries exchange their highly credible debt for the less well or less widely recognized debts of individual agents. The debt of some these financial intermediaries may then circulate as generally acceptable media of exchange.

But what constitutes creditworthiness depends on the expectations of those that judge the creditworthiness of an individual or a firm. The creditworthiness of agents depends on the value of assets that they hold, their liabilities, and their expected income streams and cash flows. Loss of income or depreciation of assets reduces agents’ creditworthiness.

Expectational disappointments always impair the creditworthiness of agents whose expectations have been disappointed, their expected income streams having been reduced or their assets depreciated. Insofar as financial intermediaries have accepted the liabilities of individuals or businesses suffering expectational disappointment, those financial intermediaries may find that their own creditworthiness has been impaired. Because the foundation of the profitability of a financial intermediary is its creditworthiness in the eyes of the general public, the impairment of creditworthiness is a potentially catastrophic event for a financial intermediary.

The interconnectedness of economic and especially financial networks implies that impairments of creditworthiness in any substantial part of an economic system may be transmitted quickly to other parts of the system. Such expectational shocks are common, but, under some circumstances, the shocks may not only be transmitted, they may be amplified, leading to a systemic crisis.

Because expectational disappointments and disturbances are ruled out by hypothesis in the ADM model, we cannot hope to gain insight into such events from the standard ADM model. It was precisely Hicks’s temporary equilibrium model that provided the tools for such an analysis, but, unfortunately those tools remain underemployed.

——————————————————————————————————————–

1 To be clear, the assumption of unit elasticity of expectations means that agents conclude that any observed price change is permanent. If agents believe that an observed price change is permanent, they must conclude that, to restore equilibrium relative prices, all other prices must change proportionately. Hicks therefore posited that, rather than use their understanding, given their information, of the causes of the price change, agents automatically extrapolate any observed price change to all other prices. Such mechanistic expectations are hard to rationalize, but Hicks’s reasoning entails that inference.