In my previous post , I discussed Keynes’s perplexing and problematic criticism of the Fisher equation in chapter 11 of the General Theory, perplexing because it is difficult to understand what Keynes is trying to say in the passage, and problematic because it is not only inconsistent with Keynes’s reasoning in earlier writings in which he essentially reproduced Fisher’s argument, it is also inconsistent with Keynes’s reasoning in chapter 17 of the General Theory in his exposition of own rates of interest and their equilibrium relationship. Scott Sumner honored me with a whole post on his blog which he entitled “Glasner on Keynes and the Fisher Effect,” quite a nice little ego boost.

After paraphrasing some of what I had written in his own terminology, Scott quoted me in responding to a dismissive comment that Krugman recently made about Milton Friedman, of whom Scott tends to be highly protective. Here’s the passage I am referring to.

PPS. Paul Krugman recently wrote the following:

Just stabilize the money supply, declared Milton Friedman, and we don’t need any of this Keynesian stuff (even though Friedman, when pressured into providing an underlying framework, basically acknowledged that he believed in IS-LM).

Actually Friedman hated IS-LM. I don’t doubt that one could write down a set of equilibria in the money market and goods market, as a function of interest rates and real output, for almost any model. But does this sound like a guy who “believed in” the IS-LM model as a useful way of thinking about macro policy?

Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy.

It turns out that IS-LM curves will look very different if one moves away from the interest rate transmission mechanism of the Keynesians. Again, here’s David:

Before closing, I will just make two side comments. First, my interpretation of Keynes’s take on the Fisher equation is similar to that of Allin Cottrell in his 1994 paper “Keynes and the Keynesians on the Fisher Effect.” Second, I would point out that the Keynesian analysis violates the standard neoclassical assumption that, in a two-factor production function, the factors are complementary, which implies that an increase in employment raises the MEC schedule. The IS curve is not downward-sloping, but upward sloping. This is point, as I have explained previously (here and here), was made a long time ago by Earl Thompson, and it has been made recently by Nick Rowe and Miles Kimball.I hope in a future post to work out in more detail the relationship between the Keynesian and the Fisherian analyses of real and nominal interest rates.

Please do. Krugman reads Glasner’s blog, and if David keeps posting on this stuff then Krugman will eventually realize that hearing a few wisecracks from older Keynesians about various non-Keynesian traditions doesn’t make one an expert on the history of monetary thought.

I wrote a comment on Scott’s blog responding to this post in which, after thanking him for mentioning me in the same breath as Keynes and Fisher, I observed that I didn’t find Krugman’s characterization of Friedman as someone who basically believed in IS-LM as being in any way implausible.

Then, about Friedman, I don’t think he believed in IS-LM, but it’s not as if he had an alternative macromodel. He didn’t have a macromodel, so he was stuck with something like an IS-LM model by default, as was made painfully clear by his attempt to spell out his framework for monetary analysis in the early 1970s. Basically he just tinkered with the IS-LM to allow the price level to be determined, rather than leaving it undetermined as in the original Hicksian formulation. Of course in his policy analysis and historical work he was not constained by any formal macromodel, so he followed his instincts which were often reliable, but sometimes not so.

So I am afraid that my take may on Friedman may be a little closer to Krugman’s than to yours. But the real point is that IS-LM is just a framework that can be adjusted to suit the purposes of the modeler. For Friedman the important thing was to deny that that there is a liquidity trap, and introduce an explicit money-supply-money-demand relation to determine the absolute price level. It’s not just Krugman who says that, it’s also Don Patinkin and Harry Johnson. Whether Krugman knows the history of thought, I don’t know, but surely Patinkin and Johnson did.

Scott responded:

I’m afraid I strongly disagree regarding Friedman. The IS-LM “model” is much more than just the IS-LM graph, or even an assumption about the interest elasticity of money demand. For instance, suppose a shift in LM also causes IS to shift. Is that still the IS-LM model? If so, then I’d say it should be called the “IS-LM tautology” as literally anything would be possible.

When I read Friedman’s work it comes across as a sort of sustained assault on IS-LM type thinking.

To which I replied:

I think that if you look at Friedman’s responses to his critics the volume Milton Friedman’s Monetary Framework: A Debate with his Critics, he said explicitly that he didn’t think that the main differences among Keynesians and Monetarists were about theory, but about empirical estimates of the relevant elasticities. So I think that in this argument Friedman’s on my side.

And finally Scott:

This would probably be easier if you provided some examples of monetary ideas that are in conflict with IS-LM. Or indeed any ideas that are in conflict with IS-LM. I worry that people are interpreting IS-LM too broadly.

For instance, do Keynesians “believe” in MV=PY? Obviously yes. Do they think it’s useful? No.

Everyone agrees there are a set of points where the money market is in equilibrium. People don’t agree on whether easy money raises interest rates or lowers interest rates. In my view the term “believing in IS-LM” implies a belief that easy money lowers rates, which boosts investment, which boosts RGDP. (At least when not at the zero bound.) Friedman may agree that easy money boosts RGDP, but may not agree on the transmission mechanism.

People used IS-LM to argue against the Friedman and Schwartz view that tight money caused the Depression. They’d say; “How could tight money have caused the Depression? Interest rates fell sharply in 1930?”

I think that Friedman meant that economists agreed on some of the theoretical building blocks of IS-LM, but not on how the entire picture fit together.

Oddly, your critique of Keynes reminds me a lot of Friedman’s critiques of Keynes.

Actually, this was not the first time that I provoked a negative response by writing critically about Friedman. Almost a year and a half ago, I wrote a post (“Was Milton Friedman a Closet Keynesian?”) which drew some critical comments from such reliably supportive commenters as Marcus Nunes, W. Peden, and Luis Arroyo. I guess Scott must have been otherwise occupied, because I didn’t hear a word from him. Here’s what I said:

Commenting on a supremely silly and embarrassingly uninformed (no, Ms. Shlaes, A Monetary History of the United States was not Friedman’s first great work, Essays in Positive Economics, Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, A Theory of the Consumption Function, A Program for Monetary Stability, and Capitalism and Freedom were all published before A Monetary History of the US was published) column by Amity Shlaes, accusing Ben Bernanke of betraying the teachings of Milton Friedman, teachings that Bernanke had once promised would guide the Fed for ever more, Paul Krugman turned the tables and accused Friedman of having been a crypto-Keynesian.

The truth, although nobody on the right will ever admit it, is that Friedman was basically a Keynesian — or, if you like, a Hicksian. His framework was just IS-LM coupled with an assertion that the LM curve was close enough to vertical — and money demand sufficiently stable — that steady growth in the money supply would do the job of economic stabilization. These were empirical propositions, not basic differences in analysis; and if they turn out to be wrong (as they have), monetarism dissolves back into Keynesianism.

Krugman is being unkind, but he is at least partly right. In his famous introduction to Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, which he called “The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement,” Friedman gave the game away when he called the quantity theory of money a theory of the demand for money, an almost shockingly absurd characterization of what anyone had ever thought the quantity theory of money was. At best one might have said that the quantity theory of money was a non-theory of the demand for money, but Friedman somehow got it into his head that he could get away with repackaging the Cambridge theory of the demand for money — the basis on which Keynes built his theory of liquidity preference — and calling that theory the quantity theory of money, while ascribing it not to Cambridge, but to a largely imaginary oral tradition at the University of Chicago. Friedman was eventually called on this bit of scholarly legerdemain by his old friend from graduate school at Chicago Don Patinkin, and, subsequently, in an increasingly vitriolic series of essays and lectures by his then Chicago colleague Harry Johnson. Friedman never repeated his references to the Chicago oral tradition in his later writings about the quantity theory. . . . But the simple fact is that Friedman was never able to set down a monetary or a macroeconomic model that wasn’t grounded in the conventional macroeconomics of his time.

As further evidence of Friedman’s very conventional theoretical conception of monetary theory, I could also cite Friedman’s famous (or, if you prefer, infamous) comment (often mistakenly attributed to Richard Nixon) “we are all Keynesians now” and the not so famous second half of the comment “and none of us are Keynesians anymore.” That was simply Friedman’s way of signaling his basic assent to the neoclassical synthesis which was built on the foundation of Hicksian IS-LM model augmented with a real balance effect and the assumption that prices and wages are sticky in the short run and flexible in the long run. So Friedman meant that we are all Keynesians now in the sense that the IS-LM model derived by Hicks from the General Theory was more or less universally accepted, but that none of us are Keynesians anymore in the sense that this framework was reconciled with the supposed neoclassical principle of the monetary neutrality of a unique full-employment equilibrium that can, in principle, be achieved by market forces, a principle that Keynes claimed to have disproved.

But to be fair, I should also observe that missing from Krugman’s take down of Friedman was any mention that in the original HIcksian IS-LM model, the price level was left undetermined, so that as late as 1970, most Keynesians were still in denial that inflation was a monetary phenomenon, arguing instead that inflation was essentially a cost-push phenomenon determined by the rate of increase in wages. Control of inflation was thus not primarily under the control of the central bank, but required some sort of “incomes policy” (wage-price guidelines, guideposts, controls or what have you) which opened the door for Nixon to cynically outflank his Democratic (Keynesian) opponents by coopting their proposals for price controls when he imposed a wage-price freeze (almost 42 years ago on August 15, 1971) to his everlasting shame and discredit.

Scott asked me to list some monetary ideas that I believe are in conflict with IS-LM. I have done so in my earlier posts (here, here, here and here) on Earl Thompson’s paper “A Reformulation of Macroeconomic Theory” (not that I am totally satisfied with Thompson’s model either, but that’s a topic for another post). Three of the main messages from Thompson’s work are that IS-LM mischaracterizes the monetary sector, because in a modern monetary economy the money supply is endogenous, not exogenous as Keynes and Friedman assumed. Second, the IS curve (or something corresponding to it) is not negatively sloped as Keynesians generally assume, but upward-sloping. I don’t think Friedman ever said a word about an upward-sloping IS curve. Third, the IS-LM model is essentially a one-period model which makes it difficult to carry out a dynamic analysis that incorporates expectations into that framework. Analysis of inflation, expectations, and the distinction between nominal and real interest rates requires a richer model than the HIcksian IS-LM apparatus. But Friedman didn’t scrap IS-LM, he expanded it to accommodate expectations, inflation, and the distinction between real and nominal interest rates.

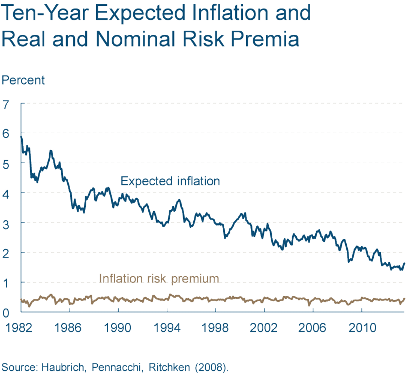

Scott’s complaint about IS-LM seems to be that it implies that easy money reduces interest rates and that tight money raises rates, but, in reality, it’s the opposite. But I don’t think that you need a macro-model to understand that low inflation implies low interest rates and that high inflation implies high interest rates. There is nothing in IS-LM that contradicts that insight; it just requires augmenting the model with a term for expectations. But there’s nothing in the model that prevents you from seeing the distinction between real and nominal interest rates. Similarly, there is nothing in MV = PY that prevented Friedman from seeing that increasing the quantity of money by 3% a year was not likely to stabilize the economy. If you are committed to a particular result, you can always torture a model in such a way that the desired result can be deduced from it. Friedman did it to MV = PY to get his 3% rule; Keynesians (or some of them) did it to IS-LM to argue that low interest rates always indicate easy money (and it’s not only Keynesians who do that, as Scott knows only too well). So what? Those are examples of the universal tendency to forget that there is an identification problem. I blame the modeler, not the model.

OK, so why am I not a fan of Friedman’s? Here are some reasons. But before I list them, I will state for the record that he was a great economist, and deserved the professional accolades that he received in his long and amazingly productive career. I just don’t think that he was that great a monetary theorist, but his accomplishments far exceeded his contributions to monetary theory. The accomplishments mainly stemmed from his great understanding of price theory, and his skill in applying it to economic problems, and his great skill as a mathematical statistician.

1 His knowledge of the history of monetary theory was very inadequate. He had an inordinately high opinion of Lloyd Mints’s History of Banking Theory which was obsessed with proving that the real bills doctrine was a fallacy, uncritically adopting its pro-currency-school and anti-banking-school bias.

2 He covered up his lack of knowledge of the history of monetary theory by inventing a non-existent Chicago oral tradition and using it as a disguise for his repackaging the Cambridge theory of the demand for money and aspects of the Keynesian theory of liquidity preference as the quantity theory of money, while deliberately obfuscating the role of the interest rate as the opportunity cost of holding money.

3 His theory of international monetary adjustment was a naïve version of the Humean Price-Specie-Flow mechanism, ignoring the tendency of commodity arbitrage to equalize price levels under the gold standard even without gold shipments, thereby misinterpreting the significance of gold shipments under the gold standard.

4 In trying to find a respectable alternative to Keynesian theory, he completely ignored all pre-Keynesian monetary theories other than what he regarded as the discredited Austrian theory, overlooking or suppressing the fact that Hawtrey and Cassel had 40 years before he published the Monetary History of the United States provided (before the fact) a monetary explanation for the Great Depression, which he claimed to have discovered. And in every important respect, Friedman’s explanation was inferior to and retrogression from Hawtrey and Cassel explanation.

5 For example, his theory provided no explanation for the beginning of the downturn in 1929, treating it as if it were simply routine business-cycle downturn, while ignoring the international dimensions, and especially the critical role played by the insane Bank of France.

6 His 3% rule was predicated on the implicit assumption that the demand for money (or velocity of circulation) is highly stable, a proposition for which there was, at best, weak empirical support. Moreover, it was completely at variance with experience during the nineteenth century when the model for his 3% rule — Peel’s Bank Charter Act of 1844 — had to be suspended three times in the next 22 years as a result of financial crises largely induced, as Walter Bagehot explained, by the restriction on creation of banknotes imposed by the Bank Charter Act. However, despite its obvious shortcomings, the 3% rule did serve as an ideological shield with which Friedman could defend his libertarian credentials against criticism for his opposition to the gold standard (so beloved of libertarians) and to free banking (the theory of which Friedman did not comprehend until late in his career).

7 Despite his professed libertarianism, he was an intellectual bully who abused underlings (students and junior professors) who dared to disagree with him, as documented in Perry Mehrling’s biography of Fischer Black, and confirmed to me by others who attended his lectures. Black was made so uncomfortable by Friedman that Black fled Chicago to seek refuge among the Keynesians at MIT.