UPDATE: My concluding paragraph was inadverently deleted from my post, so even if you’ve already read the post, you may want to go back and read my concluding paragraph.

Last December, Nathan Tankus wrote an essay for his substack site defending Arthur Burns and his record as Fed Chairman in the 1970s when inflation rose to double digits, setting the stage for Volcker’s shock therapy in 1981-82. Tankus believes that Burns has been blamed unfairly for the supposedly dreadful performance of the economy in the 1970s, a decade that probably ranks second for dreadfulness, after the 1930s, in the economic history of the 20th century. Nathan is not the first commentator or blogger I’ve seen over the past 10 years or so to offer a revisionist, favorable, take on Burns’s tenure at the Fed. Here are links to my earlier posts on Burns revisionism (link, link, link)

Nathan properly criticizes the treatment of the 1970s in journalistic mentions to that fraught decade. The decade endured a lot of unpleasantness along with the chronically high inflation that remains its most memorable feature, but it was also a decade of considerable economic growth, and, despite three recessions and rising unemployment, a huge increase in total US employment.

Nathan believes that Burns has been denigrated unfairly as a weak Fed Chairman who either ignored the inflationary forces, or succumbed, despite his conservative, anti-inflationary, political inclinations, to Nixon’s entreaties and pressure tactics, and deployed monetary policy to assist Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign. Although the latter charge has at least some validity – it’s no accident that the literature on political business cycles, especially a seminal 1975 paper on that topic by William Nordhaus, a future Nobel laureate, was inspired by the Burns-Nixon episode – it’s not the whole story.

But, what is more important than Burns being cajoled or coerced by Nixon to speed the recovery from the 1969-70 recession, is that Burns was the victim of his own conceptual error in supposing that, if the incomes policy that he favored were adtoped, monetary expansion by the Fed wouldn’t lead to the inflationary consequences that they ultimately did have. Burns’s conceptual failure — whether willful or thoughtless — was to overlook the relationship between aggregate income and inflation. Although his confusion about that critical relationship was then widely, though not universally, held, his failure seems obvious, almost banal. But there were then only a few able to both identify and explain the failure and draw the appropriate policy implications. (In an earlier post about Burns, I’ve discussed Ralph Hawtrey’s final book published in 1966, but likely never noticed by Burns, in which the confusions were clearly dispelled and the appropriate policy implications clearly delineated.)

Nathan attributes the deterioration of Burns’s reputation to the influence of Milton Friedman, who wrote his doctoral dissertation under Burns at Columbia. Friedman, to be sure, was sharply critical of Burns’s performance at the Fed, but the acerbity of Friedman’s criticism also reflects his outrage that Burns had betrayed conservative, or “free-market”, principles by helping to persuade Nixon to adopt wage-and-price controls in 1971. Though I share Friedman’s disapproval of Burns’s role in the adoption of wage-and-price controls, Burns’s monetary-policy can be assessed independently of how one views the merits of the wage-and-price controls sought by Burns.

Here’s how Nathan describes Burns:

The actual Burns was – in his time – a well respected Monetary Policy “Hawk” who believed deeply in restrictive austerity. This was nearly universally acknowledged during his tenure, and then for a few years after. A New York Times article from 1978 about Burns’s successor, George Miller illustrates this well. Entitled “Miller Fights Inflation In Arthur Burns’s Style”, the article argues that Miller tightened monetary policy far more aggressively than the Carter administration expected and spoke in conservative, inflation focused and austere terms. In other words, he was a clone of Arthur Burns.

The reason this has been forgotten is the total victory of one influential dissenter: Milton Friedman. Milton Friedman, in real time, pilloried his former mentor as a money supply expanding inflationist. That view deserves its own piece sometime (spoiler: it’s mostly wrong.)

Given Friedman’s dictum — “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” – it’s no surprise that Friedman blamed the Federal Reserve and Burns for inflation. While confidently asserting on the one hand that changes in the quantity of money cause corresponding changes in prices, Friedman, on the other hand, invoked unexplained long and variable lags between changes in the quantity of money and changes in prices to parry evidence that the supposed correlations were less than clear-cut. So, Friedman’s narrow focus on the quantity of money rather than on total spending – increaes in the quantity of money being as much an effect as a cause of increased nominal spending and income — actually undercut his critique of Fed policy. In what follows I will therefore not discuss the quantity of money, which was, in Friedman’s mind, the key variable that had to be controlled to reduce or stop inflation. Instead, I focus on the behavior of total nominal spending (aka aggregate demand) and total nominal income, which is what monetary policy (perhaps in conjunction with fiscal policy) has some useful capacity to control.

Upon becoming Fed Chairman early in 1970, Burns continued the monetary tightening initiated by his predecessor in 1969 when inflation had risen to 6%. Although the recession caused by that tightening had started only two months before Burns succeeded Martin, inflation hardly declined, notwithstanding a steady rise in unemployment from the 3.4% rate inherited by Nixon in January 1969, at the start of his Presidency, to 4.2% when Burns became Chairman, and to 6.1% at the end of 1970.

The minimal impact of recession on inflation was troubling to Burns, reinforcing his doubts about the efficacy of conventional monetary and fiscal policy tools in an economy that seemed no longer to operate as supposed by textbook theory. It wasn’t long before Burn, in Congressional testimony (5/18/1970) voiced doubts about the efficacy of monetary policy in restraining inflation.

Another deficiency in the formulation of stabilization policies in the United States has been our tendency to rely too heavily on monetary restriction as a device to curb inflation…. severely restrictive monetary policies distort the structure of production. General monetary controls… have highly uneven effects on different sectors of the economy. On the one hand, monetary restraint has relatively slight impact on consumer spending or on the investments of large businesses. On the other hand, the homebuilding industry, State and local construction, real estate firms, and other small businesses are likely to be seriously handicapped in their operations. When restrictive monetary policies are pursued vigorously over a prolonged period, these sectors may be so adversely affected that the consequences become socially and economically intolerable.

We are in the transitional period of cost-push inflation, and we therefore need to adjust our policies to the special character of the inflationary pressures that we are now experiencing. An effort to offset, through monetary and fiscal restraints, all of the upward push that rising costs are now exerting on prices would be most unwise. Such an effort would restrict aggregate demand so severely as to increase greatly the risks of a very serious business recession. . . . There may be a useful… role for an incomes policy to play in shortening the period between suppression of excess demand and restoration of reasonable price stability.

Quoted by R. Hetzel in “Arthur Burns and Inflation” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Winter 1998

The cost-push view of inflation that Burns articulated was not a new one for Burns. He had discussed it in a 1967 lecture at a seminar organized by the American Enterprise Institute concerning the wage-price guideposts, which had been invoked during the Eisenhower administration when he was CEA Chairman, and were continued in the Kennedy-Johnson administrations, to discourage labor and business from “excessive” increases in wages and prices.

The seminar consisted of two lectures, one by Burns (presumably offering a “conservative” or Republican view) and another by Paul Samuelson (offering a “liberal” or Democratic view), followed by the responses each to the other, and finally by questions from an audience of economists drawn from Washington-area universities, think-tanks and government agencies, and the responses of Burns and Samuelson. Transcripts of the lectures and the follow-up discusions were included in a volume published by AEI.

Inflation had become a contentious political issue in 1967, Republicans blaming the Johnson Administration for the highest inflation since the early 1950s. Though Burns, while voicing mild criticism of how the guideposts were administered and skepticism about their overall effect on inflation, neither rejected them on principle nor dismissed them as ineffective.

So, Burns did not arrive at the Fed as an ideological opponent of government intervention in the decisions of business and organized labor. Had Milton Friedman participated in the AEI seminar, he would have voiced implacable opposition to the guideposts as ineffective in practice and an arbitrary — extra-legal and therefore especially obnoxious — exercise of government power over the private sector. Burns’s conservatism, unlike Friedman’s, was the conventional Republican pro-business attitude, and, as Nathan himself notes, business wasn’t at all averse to government assistance in resisting union wage demands.

That doesn’t mean that Burns’s views hadn’t changed since 1967 when he voiced tepid support for guideposts as benchmarks for business and labor in setting prices and negotiating labor contracts. But the failure of monetary tightening and a deepening recession to cause more than a minimal slowdown in inflation seems to have shattered Burns’s shaky confidence that monetary policy could control inflation.

Unlike the preceding recessions in which increased (but still low) inflation quickly led to monetary tightening, the 1969-70 recession began only after inflation had risen steadily for five years from less than 2% in 1965 to 6% in 1969. It’s actually not surprising — it, at least, shouldn’t have been — that, after rising steadily for five years and becoming ingrained in public expectations, inflation would become less responsive to monetary tightening and recession than it had been before becoming ingrained in expectations. Nevertheless, the failure of a recession induced by monetary tightening to curtail inflation seems to have been considered by Burns proof that inflation is not a purely monetary phenomenon.

The further lesson drawn by Burns from the minimal decline in inflation after a year of monetary tightening followed by a recession and rising unemployment was that persistent inflation reflects the power of big business and big labor to keep raising prices and wages regardless of market conditions. The latter lesson became the basis of his approach to the inflation problem. Inflation control had to reckon with the new reality that, even if restrictive monetary and fiscal policies were adopted, it was big business and big labor that controlled pricing and inflation.

While the rationale that Burns offered for an incomes policy differed little from the rationale for the wage-price guideposts to which Burns had earlier paid lip-service, in articulating the old rationale, perhaps to provide the appearance of novelty, Burns found it useful to package the rationale in a new terminology — the vague British catchphrase “incomes policy” covering both informal wage-price guideposts and mandatory wage-price controls. The phrase helped him justify shifting monetary policy from restraint to stimulus, even though inflation was still unacceptably high, by asserting that responsibility for controlling inflation was merely being transferred, not abandoned, to another government entity with the legal power and authority to exercise that control.

It’s also noteworthy that both Burns’s diagnosis of inflation and the treatment that he recommended were remarkably similar to the diagnosis and treatment advanced in a 1967 best-selling book, The New Industrial State, by the famed Harvard economist and former adviser to President Kennedy, J. K. Galbraith.

Despite their very different political views and affiliations, Burns and Galbraith, both influenced by the Institutionalist School of economics, were skeptical of the standard neoclassical textbook paradigm. Galbraith argued that big corporations make their plans based on the prices and wages that they can impose on their smaller suppliers and smaller customers (especially, in Galbraith’s view, through the skillful deployment of modern advertising techniques) while negotiating pricing terms with labor unions and other large suppliers and with their large customers. (For more on Galbraith see this post.)

Though more sympathetic to big business and less sympathetic to big labor than Galbraith, Burns, by 1970, seems to have fully internalized, whether deliberately or inadvertently, the Galbrathian view of inflation.

Aside from his likely sincere belief that conventional anti-inflationary monetary and fiscal policy were no longer effective in an economy dominated by big business and big labor, Burns had other more political motivations for shifting his policy preferences toward direct controls over wages and prices. A full account of his thinking would require closer attention to the documentary record than I have undertaken, but, Burns was undoubtedly under pressure from Nixon to avoid a recession in the 1972 election year like the one precipitated by the Fed in 1960 when the Fed moved to suppress a minor uptick in inflation following its possibly excessive monetary stimulus after the 1957-58 recession. Burns had warned Nixon in 1960 that a looming recession might hurt his chances in the upcoming election, and Nixon thereafter blamed his 1960 loss on the Fed and on the failure of the Eisenhower adminisration to increase spending to promote recovery. Moreover, the disastrous (for Republicans) losses in the 1958 midterm elections were widely attributed to the 1957-58 recession. Substantial GOP losses in the 1970 midterms, plainly attributable to the 1970 recession, further increased Nixon’s anxiety and his pressure on Burns to hasten a recovery through monetary expansion to ensure Nixon’s reelection.

But it’s worth taking note of a subtle difference between the rationale for wage-price guideposts and the rationale for an incomes policy. While wage-price guideposts were aimed solely at individual decisions about wages and prices, the idea of an incomes policy had a macroeconomic aspect: reconciling the income demands of labor and business in a way that ensured consistency between the flow of aggregate income and low inflation. According to Burns, reconciling those diverse and conflicting income demands with low inflation required an incomes policy to prevent unrestrained individual demands for increased wages and prices from expanding the flow of income so much that inflation would be the necessary result.

What Burns and most other advocates of incomes policies overlooked is that incomes are generated from the spending decisions of households, business firms and the government. Those spending decisions are influenced by the monetary- and fiscal-policy choices of the monetary and fiscal authorities. Any combination of monetary- and fiscal-policy choices entails corresponding flows of total spending and total income. For any inflation target, there is a set of monetary- and fiscal-policy combinations that entails flows of total spending and total income consistent with that target.

Burns’s fallacy (and that of most incomes-policy supporters) was to disregard the relationship between total spending and monetary- and fiscal-policy choices. The limits on wage increases imposed by an incomes policy can be maintained only if a monetary- and fiscal-policy combination consistent with those limits is chosen. Burns’s fallacy is commonly known as the fallacy of composition: the idea that what is true for one individual in a group must be true for the group as a whole. For example, one spectator watching a ball game can get a better view of the game by standing up, but if all spectators stand up together, none of them gets a better view.

Wage increases for one worker or for workers in one firm can be limited to the percentage specified by the incomes policy, but the wage increases for all workers can’t be limited to the percentage specified by the incomes policy unless the chosen monetary- and fiscal-policy combination is consistent with that percentage.

If aggregate nominal spending and income exceed the nominal income consistent with the inflation target, only two outcomes are possible. The first, and more likely, outcome is that the demand for labor associated with the actual increase in aggregate demand will overwhelm the prescribed limit on wage increases. If it’s in the interest of workers to receive wage increases exceeding the permitted increase — and it surely is — and if it’s also in the interest of employers trying to increase output because demand for their output increases by more than expected, making it profitable to hire additional workers at increased wages, it’s hard to imagine that wages wouldn’t increase by more than the incomes policy allows. Indeed, since price increases are typically allowed only if costs increase, there’s an added incentive for firms to agree to wage increases to make price increases allowable.

Second, even if the limits on wage increases were not exceeded, those limits imply an income transfer from workers to employers. The implicit income redistribution might involve some reduction in total spending and in aggregate demand, but, ultimately, as long as the total spending and total income associated with the chosen monetary- and fiscal-policy combination exceeds the total income consistent with the inflation target, excess demands for goods will either cause domestic prices to rise or induce increased imports at increased prices, thereby depreciating the domestic currency and raising the prices of imported final goods and raw materials. Those increased prices and costs will be a further source of inflationary pressure on prices and on wages, thereby increasing inflation above the target or forcing the chosen monetary- and fiscal-policy combination to be tightened to prevent further currency depreciation.

To recapitulate, Burns actually had the glimmering of an insight into the problem of reducing inflation in an economy in which most economic agents make plans and decisions based on their inflationary expectations. When people make plans and commitments in expectation of persistent future inflation, reducing, much less stopping, inflation is hard, because doing so must disappoint their expectations, rendering the plans and commitments based on those expectations costly, or even impossible, to fulfill. The promise of an incomes policy is that, by gradually reducing inflation and facilitating the implementation of the fiscal and monetary policies necessary to reduce inflation, it can reduce expectations of inflation, thereby reducing the cost of reducing inflation by monetary and fiscal restraint.

But instead of understanding that an incomes policy aimed at reducing inflation by limiting the increases in wages and prices to percentages consistent with reduced inflation could succeed only if monetary and fiscal policies were also amed at slowing the growth of total spending and total income to rates consistent with the inflation target, Burns conducted a monetary policy with little attention to its consistency with explicit or implicit inflation targets. The failure to reduce the growth of aggregate spending and income rendered the incomes policy unfeasible, thereby ensuring the incomes policy aiming to reduce inflation would fail. The failure to grasp the impossibility of controlling wage-and-pricing decisions at the micro level without controlling aggregate spending and income at the macro level was the fatal conceptual mistake that guaranteed Burns’s failure as Fed Chairman. Perhaps Burns’s failure was tragic, but failure it was.

Let’s now look at the results of Burns’s monetary policies. The chart below shows the annual rates of change in nominal GDP and real GDP from Q1-1968 to Q1-1980

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?graph_id=1249697#

To give Burns his due, the freeze and the cost-of-living council that replaced it 90 days afterwards was a splendid political success, igniting an immediate stock-market boom and increasing Nixon’s popularity with both Democrats and Republicans notwithstanding Nixon’s repudiation of his repeated pledges never to impose wage-and-price controls. Burns continued — though erratically — the monetary easing that he began at the end of 1970, providing sufficient stimulus to reduce unemployment, which had barely budged from the peak rate of 6.1% in December 1970 to 6.0% in September 1971. While the decline in the unemployment rate was modest, to 5.6% in October 1972, the last official report before the election, total US employment between June 1970 (when US employment was at its cyclical trough) and October 1972 increased by 5%, reflecting both cyclical recovery and the beginning of an influx of babyboomers and women into the labor force.

The monetary stimulus provided by the Fed between the end of the recession in November 1970 and October 1972 can be inferred from the increase in total spending and income (as measured by nominal GDP) from Q1-1971 and Q3-1972. In that 7-quarter period, total spending and income increased by 18.6% (corresponding to an annual rate of 10.6%). Because the economy in Q4-1970 was still in a recession, nominal spending and income could increase at a faster rate during the recovery while inflation was declining than would have been consistent with the inflation target if maintained permanently.

But as the expansion continued, with employment and output expanding rapidly, the monetary stimulus should have been gradually withdrawn to slow the growth of total spending and income to a rate consistent with a low inflation target. But rather than taper off monetary stimulus, the Fed actually allowed total spending and income growth to accelerate in the next three quarters (Q4-1972 through Q2-1973) to an annual rate of 12.7%.

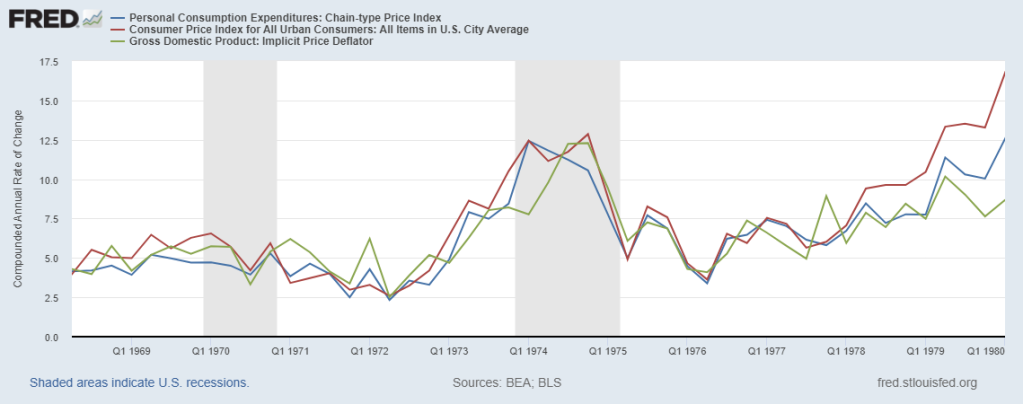

Inflation, which at first had shown only minimal signs of increasing as output and employment expanded rapidly before the 1972 election, not surprisingly began to accelerate rapidly in the first half of 1973. (The chart below provides three broadly consistent measures of inflation (Consumer Price Index, Personal Consumption Expenditures, and GDP implicit price deflator at quarterly intervals). The chart shows that all three measures show inflation rising rapidly in the first hals of 1973, with inflation in Q2-1973 in a range between 6.3% and 8.6%.

Burns rejected criticisms that the Fed was responsible for resurgent inflation, citing a variety of special factors like rising commodity prices as the cause of rising inflation. But, having allowed the growth of total spending and income to accelerate from Q4-1972 and Q2-1973, in violation of the rationale for the incomes policy that he had recommended, Burns had no credible defense of the Fed’s monetary policy.

With inflation approaching double digit levels – the highest in over 20 years – Burns and the Fed had already begun to raise interest rates in the first half of 1973, but not until the third quarter did rates rise enough to slow the growth of total spending and income. A belated tightening was, of course, in order, but, as if to compensate for its tardiness, the Fed, as it has so often been wont to do, tightened too aggressively, causing the growth of total spending to decline from 11% in Q2 1973 to less than 5% in Q3 1973, a slowdown that caused real GDP to fall, and the unemployment rate, having just reached its lowest point (4.6%) since April 1970, a rate not matched again for two decades, to start rising.

Perhaps surprised by the depth of the third-quarter slowdown, the Fed eased policy somewhat in the fourth quarter until war broke out between Egypt, Syria and Israel, soon followed by a cutback in overall oil production by OPEC and a selective boycott by Arab oil producers of countries, like the US, considered supportive of Israel. With oil prices quadrupling over the next few months, the cutback in oil production triggered a classic inflationary supply shock.

It’s now widely, though not universally, understood that the optimal policy response to a negative supply shock is not to tighten monetary policy, but to allow the price level to increase permanently and inflation to increase transitorily, with no attempt to reverse th price-level and inflation effects. But, given the Fed’s failure to prevent inflation from accelerating in the first half of 1973, the knee-jerk reaction of Burns and the Fed was to tighten monetary policy again after the brief relaxation in Q4-1973, as if previous mistakes could be rectified by another in the opposite direction.

The result was, by some measures, the deepest recession since 1937-38 with unemployment rising rapidly to 9% by May 1975. Because of the negative supply shock, most measures of inflation, despite monetary tightening, were above 10% for almost all of 1974. While the reduction in nominal GDP growth during the recession was only to 8%, which, under normal conditions, would have been excessive, the appropriate target for NGDP growth, given the severity of the supply shock that was causing both labor and capital to be idled, would, at least initially, have been closer to the pre-recession rate of 12.7% than to 8%. The monetary response to a supply shock should take into account that, at least during the contraction and even in the early stages of a recovery, monetary expansion, by encouraging the reemployment of resources, thereby moderating the decline in output, can actually be disinflationary.

I pause here to observe that inflation need not increase just because unemployment is falling. That is an inference often mistakenly drawn from the Phillips Curve relationship between unemployment and inflation. It is a naive and vulgar misunderstanding of the Phillips Curve to assume that dcelining unemployment is always and everywhere inflationary. The kernel of truth in that inference is that monetary expansion tends to be inflationary when the economy operates at close to full employment without sufficient slack to allow output to increase in proportion to an increase in aggregate spending. However, when the economy is operating with slack and is far from full employment, the inference is invalid and counter-productive.

Burns eventually did loosen monetary policy to promote recovery in the second half of 1975, output expanding rapidly even as inflation declined to the mid-single digits while unemployment fell from 9% in May 1975 to 7.7% in October 1976. But, just as it did after the 1972 Presidential election, growth of NGDP actually increased after the 1976 Presidential election.

In the seven quarters from Q1-1975 through Q3-1976, nominal GDP grew at an average annual rate of 10.2%, with inflation fallng from a 7.7% to 9.4% range in Q1-1975 to a 5.3% to 6.5% range in Q3-1976; in the four quarters from Q4-1976 through Q3-1977, nominal GDP grew at an average rate of 10.9%, with inflation remaining roughly unchanged (in the 5% to 6.2% range). Burns may have been trying to accommodate the desires of the Carter Administration to promote a rapid reduction in unemployment as Carter had promised as a Presidential candidate. Unemployment in March 1977 stood at 7.4% no less than it was in May 1976. While the unemployment rate was concerning, unemployment rates in the 1970s reflected the influx of baby boomers and women lacking work experience into work force, which tended to increase measured unemployment despite rapid job growth. Between May 1976 and March 1977, for example, an average of over 200,000 new jobs a month were filled despite an unchanged unemployment rate.

As it became evident, towards the end of 1977 that Burns would not be reappointed Chairman, and someone else more amentable to providing further monetary stimulus would replace him, the dollar started falling in foreign-exchange markets, almost 7% between September 1977 and March 1978, a depreciation that provoked a countervailing monetary tightening and an increase in interest rates by the Fed. The depreciation and the tightening were reflected in reduced NGDP growth and increased inflation in Q4 1977 and Q1 1978 just as Burns was being replaced by his successor G. William Miller in March 1978.

So, a retrospective on Burns’s record as Fed Chairman provides no support for a revisionist rehabilitation of that record. Not only did Burns lack a coherent theoretical understanding of the effects of monetary policy on macroeconomic performance, which, to be fair, didn’t set him apart from his predecessors or successors, but he allowed himself to be beguiled by the idea of an incomes policy as an alternative to monetary policy as a way to control inflation. Had he properly understood the rationale of an incomes policy, he would have realized that it could serve a useful function only insofar as it supplemented, not replaced, a monetary policy aiming to reduce the growth of aggregate demand to a rate consistent with reducing inflation. Instead, Burns viewed the incomes policy as a means to eliminate the upward pressure of wage increases on costs, increases that, for the most part, merely compensated workers for real-wage reductions resulting from previous unanticipated inflation. But the cause of the cost-push phenomenon that was so concerning to Burns is aggregate-demand growth, which either raises prices or encourages output increases that make it profitable for businesses to incur those increased costs. Burns’s failure to grasp these causal relationships led him to a series of incoherent policy decisions that gravely damaged the US economy.