In my previous post, I tried to explain how to think about own rates of interest. Unfortunately, I made a careless error in calculating the own rate of interest in the simple example I constructed to capture the essence of Sraffa’s own-rate argument against Hayek’s notion of the natural rate of interest. But sometimes these little slip-ups can be educational, so I am going to try to turn my conceptual misstep to advantage in working through and amplifying the example I presented last time.

But before I reproduce the passage from Sraffa’s review that will serve as our basic text in this post as it did in the previous post, I want to clarify another point. The own rate of interest for a commodity may be calculated in terms of any standard of value. If I borrow wheat and promise to repay in wheat, the wheat own rate of interest may be calculated in terms of wheat or in terms of any other standard; all of those rates are own rates, but each is expressed in terms of a different standard.

Lend me 100 bushels of wheat today, and I will pay you back 102 bushels next year. The own rate of interest for wheat in terms of wheat would be 2%. Alternatively, I could borrow $100 of wheat today and promise to pay back $102 of wheat next year. The own rate of interest for wheat in terms of wheat and the own rate of interest for wheat in terms of dollars would be equal if and only if the forward dollar price of wheat is the same as the current dollar price of wheat. The commodity or asset in terms of which a price is quoted or in terms of which we measure the own rate is known as the numeraire. (If all that Sraffa was trying to say in criticizing Hayek was that there are many equivalent ways of expressing own interest rates, he was making a trivial point. Perhaps Hayek didn’t understand that trivial point, in which case the rough treatment he got from Sraffa was not undeserved. But it seems clear that Sraffa was trying — unsuccessfully — to make a more substantive point than that.)

In principle, there is a separate own rate of interest for every commodity and for every numeraire. If there are n commodities, there are n potential numeraires, and n own rates can be expressed in terms of each numeraire. So there are n-squared own rates. Each own rate can be thought of as equilibrating the demand for loans made in terms of a given commodity and a given numeraire. But arbitrage constraints tightly link all these separate own rates together. If it were cheaper to borrow in terms of one commodity than another, or in terms of one numeraire than another, borrowers would switch to the commodity and numeraire with the lowest cost of borrowing, and if it were more profitable to lend in terms of one commodity, or in terms of one numeraire, than another, lenders would switch to lending in terms of the commodity or numeraire with the highest return.

Thus, competition tends to equalize own rates across all commodities and across all numeraires. Of course, perfect arbitrage requires the existence of forward markets in which to contract today for the purchase or sale of a commodity at a future date. When forward markets don’t exist, some traders may anticipate advantages to borrowing or lending in terms of particular commodities based on their expectations of future prices for those commodities. The arbitrage constraint on the variation of interest rates was discovered and explained by Irving Fisher in his great work Appreciation and Interest.

It is clear that if the unit of length were changed and its change were foreknown, contracts would be modified accordingly. Suppose a yard were defined (as once it probably was) to be the length of the king’s girdle, and suppose the king to be a child. Everybody would then know that the “yard” would increase with age and a merchant who should agree to deliver 1000 “yards” ten years hence, would make his terms correspond to his expectations. To alter the mode of measurement does not alter the actual quantities involved but merely the numbers by which they are represented. (p. 1)

We thus see that the farmer who contracts a mortgage in gold is, if the interest is properly adjusted, no worse and no better off than if his contract were in a “wheat” standard or a “multiple” standard. (p. 16)

I pause to make a subtle, but, I think, an important, point. Although the relationship between the spot and the forward price of any commodity tightly constrains the own rate for that commodity, the spot/forward relationship does not determine the own rate of interest for that commodity. There is always some “real” rate reflecting a rate of intertemporal exchange that is consistent with intertemporal equilibrium. Given such an intertemporal rate of exchange — a real rate of interest — the spot/forward relationship for a commodity in terms of a numeraire pins down the own rate for that commodity in terms of that numeraire.

OK with that introduction out of the way, let’s go back to my previous post in which I wrote the following:

Sraffa correctly noted that arbitrage would force the terms of such a loan (i.e., the own rate of interest) to equal the ratio of the current forward price of the commodity to its current spot price, buying spot and selling forward being essentially equivalent to borrowing and repaying.

That statement now seems quite wrong to me. Sraffa did not assert that arbitrage would force the own rate of interest to equal the ratio of the spot and forward prices. He merely noted that in a stationary equilibrium with equality between all spot and forward prices, all own interest rates would be equal. I criticized him for failing to note that in a stationary equilibrium all own rates would be zero. The conclusion that all own rates would be zero in a stationary equilibrium might in fact be valid, but if it is, it is not as obviously valid as I suggested, and my criticism of Sraffa and Ludwig von Mises for not drawing what seemed to me an obvious inference was not justified. To conclude that own rates are zero in a stationary equilibrium, you would, at a minimum, have to show that there is at least one commodity which could be carried from one period to the next at a non-negative profit. Sraffa may have come close to suggesting such an assumption in the passage in which he explains how borrowing to buy cotton spot and immediately selling cotton forward can be viewed as the equivalent of contracting a loan in terms of cotton, but he did not make that assumption explicitly. In any event, I mistakenly interpreted him to be saying that the ratio of the spot and forward prices is the same as the own interest rate, which is neither true nor what Sraffa meant.

And now let’s finally go back to the key quotation of Sraffa’s that I tried unsuccessfully to parse in my previous post.

Suppose there is a change in the distribution of demand between various commodities; immediately some will rise in price, and others will fall; the market will expect that, after a certain time, the supply of the former will increase, and the supply of the latter fall, and accordingly the forward price, for the date on which equilibrium is expected to be restored, will be below the spot price in the case of the former and above it in the case of the latter; in other words, the rate of interest on the former will be higher than on the latter. (“Dr. Hayek on Money and Capital,” p. 50)

In my previous post I tried to flesh out Sraffa’s example by supposing that, in the stationary equilibrium before the demand shift, tomatoes and cucumbers were both selling for a dollar each. In a stationary equilibrium, tomato and cucumber prices would remain, indefinitely into the future, at a dollar each. A shift in demand from tomatoes to cucumbers upsets the equilibrium, causing the price of tomatoes to fall to, say, $.90 and the price of cucumbers to rise to, say, $1.10. But Sraffa also argued that the prices of tomatoes and cucumbers would diverge only temporarily from their equilibrium values, implicitly assuming that the long-run supply curves of both tomatoes and cucumbers are horizontal at a price of $1 per unit.

I misunderstood Sraffa to be saying that the ratio of the future price and the spot price of tomatoes equals one plus the own rate on tomatoes. I therefore incorrectly calculated the own rate on tomatoes as 1/.9 minus one or 11.1%. There were two mistakes. First, I incorrectly inferred that equality of all spot and forward prices implies that the real rate must be zero, and second, as Nick Edmunds pointed out in his comment, a forward price exceeding the spot price would actually be reflected in an own rate less than the zero real rate that I had been posited. To calculate the own rate on tomatoes, I ought to have taken the ratio of spot price to the forward price — (.9/1) — and subtracted one plus the real rate. If the real rate is zero, then the implied own rate is .9 minus 1, or -10%.

To see where this comes from, we can take the simple algebra from Fisher (pp. 8-9). Let i be the interest rate calculated in terms of one commodity and one numeraire, and j be the rate of interest calculated in terms of a different commodity in that numeraire. Further, let a be the rate at which the second commodity appreciates relative to the first commodity. We have the following relationship derived from the arbitrage condition.

(1 + i) = (1 + j)(1 + a)

Now in our case, we are trying to calculate the own rate on tomatoes given that tomatoes are expected (an expectation reflected in the forward price of tomatoes) to appreciate by 10% from $.90 to $1.00 over the term of the loan. To keep the analysis simple, assume that i is zero. Although I concede that a positive real rate may be consistent with the stationary equilibrium that I, following Sraffa, have assumed, a zero real rate is certainly not an implausible assumption, and no important conclusions of this discussion hinge on assuming that i is zero.

To apply Fisher’s framework to Sraffa’s example, we need only substitute the ratio of the forward price of tomatoes to the spot price — [p(fwd)/p(spot)] — for the appreciation factor (1 + a).

So, in place of the previous equation, I can now substitute the following equivalent equation:

(1 + i) = (1 + j) [p(fwd)/p(spot)].

Rearranging, we get:

[p(spot)/p(fwd)] (1 + i) = (1 + j).

If i = 0, the following equation results:

[p(spot)/p(fwd)] = (1 + j).

In other words:

j = [p(spot)/p(fwd)] – 1.

If the ratio of the spot to the forward price is .9, then the own rate on tomatoes, j, equals -10%.

My assertion in the previous post that the own rate on cucumbers would be negative by the amount of expected depreciation (from $1.10 to $1) in the next period was also backwards. The own rate on cucumbers would have to exceed the zero equilibrium real rate by as much as cucumbers would depreciate at the time of repayment. So, for cucumbers, j would equal 11%.

Just to elaborate further, let’s assume that there is a third commodity, onions, and that, in the initial equilibrium, the unit prices of onions, tomatoes and cucumbers are equal. If the demand shift from tomatoes to cucumbers does not affect the demand for onions, then, even after the shift in demand, the price of onions will remain one dollar per onion.

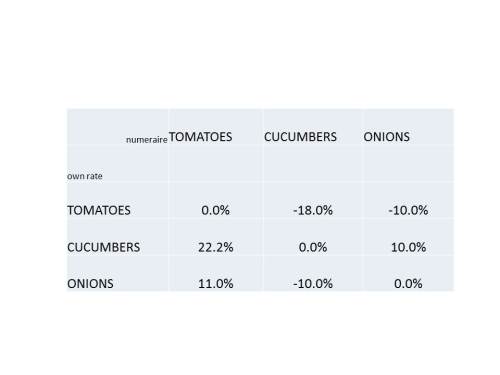

The table below shows prices and own rates for tomatoes, cucumbers and onions for each possible choice of numeraire. If prices are quoted in tomatoes, the price of tomatoes is fixed at 1. Given a zero real rate, the own rate on tomatoes in period is zero. What about the own rate on cucumbers? In period 0, with no change in prices expected, the own rate on cucumbers is also zero. However in period 1, after the price of cucumbers has risen to 1.22 tomatoes, the own rate on cucumbers must reflect the expected reduction in the price of a cucumber in terms of tomatoes from 1.22 tomatoes in period 1 to 1 tomato in period 2, a price reduction of 22% percent in terms of tomatoes, implying a cucumber own rate of 22% in terms of tomatoes. Similarly, the onion own rate in terms of tomatoes would be 11% percent reflecting a forward price for onions in terms of tomatoes 11% below the spot price for onions in terms of tomatoes. If prices were quoted in terms of cucumbers, the cucumber own rate would be zero, and because the prices of tomatoes and onions would be expected to rise in terms of cucumbers, the tomato and onion own rates would be negative (-18.2% for tomatoes and -10% for onions). And if prices were quoted in terms of onions, the onion own rate would be zero, while the tomato own rate, given the expected appreciation of tomatoes in terms of onions, would be negative (-10%), and the cucumber own rate, given the expected depreciation of cucumbers in terms of onions, would be positive (10%).

The next table, summarizing the first one, is a 3 by 3 matrix showing each of the nine possible combinations of numeraires and corresponding own rates.

Thus, although the own rates of the different commodities differ, and although the commodity own rates differ depending on the choice of numeraire, the cost of borrowing (and the return to lending) is equal regardless of which commodity and which numeraire is chosen. As I stated in my previous post, Sraffa believed that, by showing that own rates can diverge, he showed that Hayek’s concept of a natural rate of interest was a nonsense notion. However, the differences in own rates, as Fisher had already showed 36 years earlier, are purely nominal. The underlying real rate, under Sraffa’s own analysis, is independent of the own rates.

Moreover, as I pointed out in my previous post, though the point was made in the context of a confused exposition of own rates, whenever the own rate for a commodity is negative, there is an incentive to hold it now for sale in the next period at a higher price it would fetch in the current period. It is therefore only possible to observe negative own rates on commodities that are costly to store. Only if the cost of holding a commodity is greater than its expected appreciation would it not be profitable to withhold the commodity from sale this period and to sell instead in the following period. The rate of appreciation of a commodity cannot exceed the cost of storing it (as a percentage of its price).

What do I conclude from all this? That neither Sraffa nor Hayek adequately understood Fisher. Sraffa seems to have argued that there would be multiple real own rates of interest in disequilibrium — or at least his discussion of own rates seem to suggest that that is what he thought — while Hayek failed to see that there could be multiple nominal own rates. Fisher provided a definitive exposition of the distinction between real and nominal rates that encompasses both own rates and money rates of interest.

A. C. Pigou, the great and devoted student of Alfred Marshall, and ultimately his successor at Cambridge, is supposed to have said “It’s all in Marshall.” Well, one could also say “it’s all in Fisher.” Keynes, despite going out of his way in Chapter 12 of the General Theory to criticize Fisher’s distinction between the real and nominal rates of interest, actually vindicated Fisher’s distinction in his exposition of own rates in Chapter 17 of the GT, providing a valuable extension of Fisher’s analysis, but apparently failing to see the connection between his discussion and Fisher’s, and instead crediting Sraffa for introducing the own-rate analysis, even as he undermined Sraffa’s ambiguous suggestion that real own rates could differ. Go figure.