I want to begin this post by saying that I’m flattered by, and grateful to, Frances Coppola for the first line of her blog post yesterday. But – and I note that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery – I fear I have to take issue with her over competitive devaluation.

Frances quotes at length from a quotation from Hawtrey’s Trade Depression and the Way Out that I used in a post I wrote almost four years ago. Hawtrey explained why competitive devaluation in the 1930s was – and in my view still is – not a problem (except under extreme assumptions, which I will discuss at the end of this post). Indeed, I called competitive devaluation a free lunch, providing her with a title for her post. Here’s the passage that Frances quotes:

This competitive depreciation is an entirely imaginary danger. The benefit that a country derives from the depreciation of its currency is in the rise of its price level relative to its wage level, and does not depend on its competitive advantage. If other countries depreciate their currencies, its competitive advantage is destroyed, but the advantage of the price level remains both to it and to them. They in turn may carry the depreciation further, and gain a competitive advantage. But this race in depreciation reaches a natural limit when the fall in wages and in the prices of manufactured goods in terms of gold has gone so far in all the countries concerned as to regain the normal relation with the prices of primary products. When that occurs, the depression is over, and industry is everywhere remunerative and fully employed. Any countries that lag behind in the race will suffer from unemployment in their manufacturing industry. But the remedy lies in their own hands; all they have to do is to depreciate their currencies to the extent necessary to make the price level remunerative to their industry. Their tardiness does not benefit their competitors, once these latter are employed up to capacity. Indeed, if the countries that hang back are an important part of the world’s economic system, the result must be to leave the disparity of price levels partly uncorrected, with undesirable consequences to everybody. . . .

The picture of an endless competition in currency depreciation is completely misleading. The race of depreciation is towards a definite goal; it is a competitive return to equilibrium. The situation is like that of a fishing fleet threatened with a storm; no harm is done if their return to a harbor of refuge is “competitive.” Let them race; the sooner they get there the better. (pp. 154-57)

Here’s Frances’s take on Hawtrey and me:

The highlight “in terms of gold” is mine, because it is the key to why Glasner is wrong. Hawtrey was right in his time, but his thinking does not apply now. We do not value today’s currencies in terms of gold. We value them in terms of each other. And in such a system, competitive devaluation is by definition beggar-my-neighbour.

Let me explain. Hawtrey defines currency values in relation to gold, and advertises the benefit of devaluing in relation to gold. The fact that gold is the standard means there is no direct relationship between my currency and yours. I may devalue my currency relative to gold, but you do not have to: my currency will be worth less compared to yours, but if the medium of account is gold, this does not matter since yours will still be worth the same amount in terms of gold. Assuming that the world price of gold remains stable, devaluation therefore principally affects the DOMESTIC price level. As Hawtrey says, there may additionally be some external competitive advantage, but this is not the principal effect and it does not really matter if other countries also devalue. It is adjusting the relationship of domestic wages and prices in terms of gold that matters, since this eventually forces down the price of finished goods and therefore supports domestic demand.

Conversely, in a floating fiat currency system such as we have now, if I devalue my currency relative to yours, your currency rises relative to mine. There may be a domestic inflationary effect due to import price rises, but we do not value domestic wages or the prices of finished goods in terms of other currencies, so there can be no relative adjustment of wages to prices such as Hawtrey envisages. Devaluing the currency DOES NOT support domestic demand in a floating fiat currency system. It only rebalances the external position by making imports relatively more expensive and exports relatively cheaper.

This difference is crucial. In a gold standard system, devaluing the currency is a monetary adjustment to support domestic demand. In a floating fiat currency system, itis an external adjustment to improve competitiveness relative to other countries.

Actually, Frances did not quote the entire passage from Hawtrey that I reproduced in my post, and Frances would have done well to quote from, and to think carefully about, what Hawtrey said in the paragraphs preceding the ones she quoted. Here they are:

When Great Britain left the gold standard, deflationary measure were everywhere resorted to. Not only did the Bank of England raise its rate, but the tremendous withdrawals of gold from the United States involved an increase of rediscounts and a rise of rates there, and the gold that reached Europe was immobilized or hoarded. . . .

The consequence was that the fall in the price level continued. The British price level rose in the first few weeks after the suspension of the gold standard, but then accompanied the gold price level in its downward trend. This fall of prices calls for no other explanation than the deflationary measures which had been imposed. Indeed what does demand explanation is the moderation of the fall, which was on the whole not so steep after September 1931 as before.

Yet when the commercial and financial world saw that gold prices were falling rather than sterling prices rising, they evolved the purely empirical conclusion that a depreciation of the pound had no effect in raising the price level, but that it caused the price level in terms of gold and of those currencies in relation to which the pound depreciated to fall.

For any such conclusion there was no foundation. Whenever the gold price level tended to fall, the tendency would make itself felt in a fall in the pound concurrently with the fall in commodities. But it would be quite unwarrantable to infer that the fall in the pound was the cause of the fall in commodities.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that the depreciation of any currency, by reducing the cost of manufacture in the country concerned in terms of gold, tends to lower the gold prices of manufactured goods. . . .

But that is quite a different thing from lowering the price level. For the fall in manufacturing costs results in a greater demand for manufactured goods, and therefore the derivative demand for primary products is increased. While the prices of finished goods fall, the prices of primary products rise. Whether the price level as a whole would rise or fall it is not possible to say a priori, but the tendency is toward correcting the disparity between the price levels of finished products and primary products. That is a step towards equilibrium. And there is on the whole an increase of productive activity. The competition of the country which depreciates its currency will result in some reduction of output from the manufacturing industry of other countries. But this reduction will be less than the increase in the country’s output, for if there were no net increase in the world’s output there would be no fall of prices.

So Hawtrey was refuting precisely the argument raised by Frances. Because the value of gold was not stable after Britain left the gold standard and depreciated its currency, the deflationary effect in other countries was mistakenly attributed to the British depreciation. But Hawtrey points out that this reasoning was backwards. The fall in prices in the rest of the world was caused by deflationary measures that were increasing the demand for gold and causing prices in terms of gold to continue to fall, as they had been since 1929. It was the fall in prices in terms of gold that was causing the pound to depreciate, not the other way around

Frances identifies an important difference between an international system of fiat currencies in which currency values are determined in relationship to each other in foreign exchange markets and a gold standard in which currency values are determined relative to gold. However, she seems to be suggesting that currency values in a fiat money system affect only the prices of imports and exports. But that can’t be so, because if the prices of imports and exports are affected, then the prices of the goods that compete with imports and exports must also be affected. And if the prices of tradable goods are affected, then the prices of non-tradables will also — though probably with a lag — eventually be affected as well. Of course, insofar as relative prices before the change in currency values were not in equilibrium, one can’t predict that all prices will adjust proportionately after the change.

To make the point in more abstract terms, the principle of purchasing power parity (PPP) operates under both a gold standard and a fiat money standard, and one can’t just assume that the gold standard has some special property that allows PPP to hold, while PPP is somehow disabled under a fiat currency system. Absent an explanation of why PPP doesn’t hold in a floating fiat currency system, the assertion that devaluing a currency (i.e., driving down the exchange value of one currency relative to other currencies) “is an external adjustment to improve competitiveness relative to other countries” is baseless.

I would also add a semantic point about this part of Frances’s argument:

We do not value today’s currencies in terms of gold. We value them in terms of each other. And in such a system, competitive devaluation is by definition beggar-my-neighbour.

Unfortunately, Frances falls into the common trap of believing that a definition actually tell us something about the real word, when in fact a definition tell us no more than what meaning is supposed to be attached to a word. The real world is invariant with respect to our definitions; our definitions convey no information about reality. So for Frances to say – apparently with the feeling that she is thereby proving her point – that competitive devaluation is by definition beggar-my-neighbour is completely uninformative about happens in the world; she is merely informing us about how she chooses to define the words she is using.

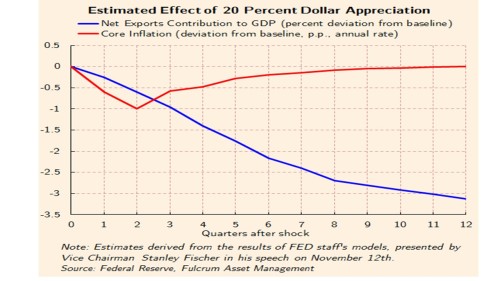

Frances goes on to refer to this graph taken from Gavyn Davies in the Financial Times, concerning a speech made by Stanley Fischer about research done by Fed staff economists showing that the 20% appreciation in the dollar over the past 18 months has reduced the rate of US inflation by as much as 1% and is projected to cause US GDP in three years to be about 3% lower than it would have been without dollar appreciation.

Frances focuses on these two comments by Gavyn. First:

Importantly, the impact of the higher exchange rate does not reverse itself, at least in the time horizon of this simulation – it is a permanent hit to the level of GDP, assuming that monetary policy is not eased in the meantime.

And then:

According to the model, the annual growth rate should have dropped by about 0.5-1.0 per cent by now, and this effect should increase somewhat further by the end of this year.

Then, Frances continues:

But of course this assumes that the US does not ease monetary policy further. Suppose that it does?

The hit to net exports shown on the above graph is caused by imports becoming relatively cheaper and exports relatively more expensive as other countries devalue. If the US eased monetary policy in order to devalue the dollar support nominal GDP, the relative prices of imports and exports would rebalance – to the detriment of those countries attempting to export to the US.

What Frances overlooks is that by easing monetary policy to support nominal GDP, the US, aside from moderating or reversing the increase in its real exchange rate, would have raised total US aggregate demand, causing US income and employment to increase as well. Increased US income and employment would have increased US demand for imports (and for the products of American exporters), thereby reducing US net exports and increasing aggregate demand in the rest of the world. That was Hawtrey’s argument why competitive devaluation causes an increase in total world demand. Francis continues with a description of the predicament of the countries affected by US currency devaluation:

They have three choices: they respond with further devaluation of their own currencies to support exports, they impose import tariffs to support their own balance of trade, or they accept the deflationary shock themselves. The first is the feared “competitive devaluation” – exporting deflation to other countries through manipulation of the currency; the second, if widely practised, results in a general contraction of global trade, to everyone’s detriment; and you would think that no government would willingly accept the third.

But, as Hawtrey showed, competitive devaluation is not a problem. Depreciating your currency cushions the fall in nominal income and aggregate demand. If aggregate demand is kept stable, then the increased output, income, and employment associated with a falling exchange rate will spill over into a demand for the exports of other countries and an increase in the home demand for exportable home products. So it’s a win-win situation.

However, the Fed has permitted passive monetary tightening over the last eighteen months, and in December 2015 embarked on active monetary tightening in the form of interest rate rises. Davies questions the rationale for this, given the extraordinary rise in the dollar REER and the growing evidence that the US economy is weakening. I share his concern.

And I share his concern, too. So what are we even arguing about? Equally troubling is how passive tightening has reduced US demand for imports and for US exportable products, so passive tightening has negative indirect effects on aggregate demand in the rest of the world.

Although currency depreciation generally tends to increase the home demand for imports and for exportables, there are in fact conditions when the general rule that competitive devaluation is expansionary for all countries may be violated. In a number of previous posts (e.g., this, this, this, this and this) about currency manipulation, I have explained that when currency depreciation is undertaken along with a contractionary monetary policy, the terms-of-trade effect predominates without any countervailing effect on aggregate demand. If a country depreciates its exchange rate by intervening in foreign-exchange markets, buying foreign currencies with its own currency, thereby raising the value of foreign currencies relative to its own currency, it is also increasing the quantity of the domestic currency in the hands of the public. Increasing the quantity of domestic currency tends to raise domestic prices, thereby reversing, though probably with a lag, the effect on the currency’s real exchange rate. To prevent the real-exchange rate from returning to its previous level, the monetary authority must sterilize the issue of domestic currency with which it purchased foreign currencies. This can be done by open-market sales of assets by the cental bank, or by imposing increased reserve requirements on banks, thereby forcing banks to hold the new currency that had been created to depreciate the home currency.

This sort of currency manipulation, or exchange-rate protection, as Max Corden referred to it in his classic paper (reprinted here), is very different from conventional currency depreciation brought about by monetary expansion. The combination of currency depreciation and tight money creates an ongoing shortage of cash, so that the desired additional cash balances can be obtained only by way of reduced expenditures and a consequent export surplus. Since World War II, Japan, Germany, Taiwan, South Korea, and China are among the countries that have used currency undervaluation and tight money as a mechanism for exchange-rate protectionism in promoting industrialization. But exchange rate protection is possible not only under a fiat currency system. Currency manipulation was also possible under the gold standard, as happened when the France restored the gold standard in 1928, and pegged the franc to the dollar at a lower exchange rate than the franc had reached prior to the restoration of convertibility. That depreciation was accompanied by increased reserve requirements on French banknotes, providing the Bank of France with a continuing inflow of foreign exchange reserves with which it was able to pursue its insane policy of accumulating gold, thereby precipitating, with a major assist from the high-interest rate policy of the Fed, the deflation that turned into the Great Depression.

Does anyone remember whether Coppola believes that aggressive QE can increase inflation expectations and employment?

I suspect Coppola might believe in a variant of MMT. I know she used to work with John Aziz.

LikeLike

TravisV,

I’m fairly sure Frances Coppola has he same jaundiced view of conventional QE that most of us have. As to whether she backs a “variant on MMT”, one element of MMT is that in a recession, the state should simply print money and spend it (and/or cut taxes), which is no more than Keynes suggested in the early 1930s.

At the debate in the European Parliament yesterday organised by Positive Money, she pointed to a few possible problems with the latter “print and spend” idea, but didn’t basically object to it.

LikeLike

Hawtrey goes off the rails in the first three sentences quoted above. That’s:

“This competitive depreciation is an entirely imaginary danger. The benefit that a country derives from the depreciation of its currency is in the rise of its price level relative to its wage level, and does not depend on its competitive advantage. If other countries depreciate their currencies, its competitive advantage is destroyed, but the advantage of the price level remains both to it and to them.”

So why does the “rise of its price level” occur? It’s because (e.g. in the case of the UK) the price of imported goods rises in terms of pounds. But if all other countries then do a “competitive devaluation”, then the price of those goods in terms of pounds revers to its original level. So, contrary to Hawtrey’s claims, the “advantage of the price level” DOES NOT remain.

LikeLike

Ralph, The rise in the price level indeed comes from an increase in the price of imports, but not only from an increase in the price of imports. The central bank depreciates its currency through purchases of the foreign currency with its own currency. Do you believe that the increase in the quantity of domestic currency has no effect on domestic prices?

LikeLike

“However, she seems to be suggesting that currency values in a fiat money system …”

And what you wrote after that suggests that the two systems do not result in the kind of fundamentally different reaction that Coppola so strongly states, and that she is mistaken on that. The gold system is not unique in that particular way.

That’s reassuring, because that was my impression, and I agree with your logic.

LikeLike

I agree completely. The final result is an increase in global demand. This is the Question mark.

On the contrary, in gold standard, if some countries decide to stay in, and other to exit, there is the possibility of no increase in global demand, if only in the second group at the cost of “Begar my neighborhood” of the first group.

LikeLike

David, Re your Feb 18th 9.18 comment just above, if the Bank of England for example prints pounds and purchases dollars, those dollars are the property of the BoE. I.e. those dollars do not get into the private sector.

Clearly an “increase in the quantity of domestic currency” would raise demand if the extra money WAS IN THE HANDS of the private sector. But it isn’t. So I don’t see an effect there. Or perhaps I’ve missed something.

Anyway, thanks for raising this topic. It’s complicated and I’m half way to a nervous breakdown trying to get my head round it…:-)

LikeLike

The gold reference is a red herring. Hawtrey was correct that two impacts of devaluation one external and one internal. The external is cancelled out if other countries devalue but that leaves internal. If internal devaluation impact is relative to wages then never reach full employment as Hawtrey suggests because no one can afford the goods. There could though be secondary impacts of price and wage inflation, plus redistribution by reducing debts and cash/bond assets.

LikeLike

JKH, I think that Coppola’s point is simply that two currencies cannot simultaneously devalue in terms of the other while under a gold standard two currencies can simultaneously devalue in terms of gold. That is a trivial, but true, point. But she seems to think it has more trivial implications.

Miguel, I think even countries remaining on the gold standard could benefit from the expansion of countries leaving the gold standard. But that benefit might be more than offset by the deflationary effects of the expectation that the countries still on the gold standard would eventually go off the gold standard.

Ralph, But under your scenario, it is the pound which is being devalued and the quantity of pounds outside the central bank is increasing.

Jason E, The internal devaluation effect may reduce the real wage age rate, but aggregate labor income tends to rise because of the increase in employment.

LikeLike

David,

agreed

although I think it remains possible for two non-gold-linked currencies to simultaneously devalue against a (global) “CPI standard”.

i.e. both currencies buy that much less when such a measure of inflation increases in an unexpected way

pointing to the idea that this is still one way in which the gold standard is not so unique

(Nick Rowe wrote an interesting post on this a few years back, which you’ve probably seen)

LikeLike

I suspect that Frances is coming into this with an eye towards the negative rate policies in Sweden and Switzerland which to my eye pretty much exactly fit the description you gave in your exception section (likely contractionary monetary policy coupled with depreciation). I’m thinking of Izzy Kaminska’s writing here. Genuinely curious, David and JKH, do you agree?

LikeLike

I believe FC’s rejoinder has surfed the same fallacy once again.

But on a different tack, allocating criticism more evenly, I would take issue with your description here:

“If a country depreciates its exchange rate by intervening in foreign-exchange markets, buying foreign currencies with its own currency, thereby raising the value of foreign currencies relative to its own currency, it is also increasing the quantity of the domestic currency in the hands of the public. Increasing the quantity of domestic currency tends to raise domestic prices, thereby reversing, though probably with a lag, the effect on the currency’s real exchange rate. To prevent the real-exchange rate from returning to its previous level, the monetary authority must sterilize the issue of domestic currency with which it purchased foreign currencies. This can be done by open-market sales of assets by the central bank, or by imposing increased reserve requirements on banks, thereby forcing banks to hold the new currency that had been created to depreciate the home currency.”

I believe that’s a standard textbook description, more or less.

But in fact, the central bank has no choice in the matter. The bank must ensure that an interest rate is paid on the resulting liability configuration in order to provide support for the target rate payable on bank reserves. You’ve pointed out two operational methods of achieving that, but again, there is no option not to do this one way or the other. In addition, dealing with this “resulting liability configuration” includes as possibilities the standard response of government debt issuance (which drains the bank reserves created) and the not-so-standard response of leaving excess bank reserves in place and paying a target interest rate on them.

So I think the priority operational response is the short term interest rate control one – not so much something “to prevent the real-exchange rate from returning to its previous level, the monetary authority must sterilize the issue of domestic currency with which it purchased foreign currencies.” I think the FX response, whatever it is, is a by-product of the interest rate one. There is no alternative to the interest rate response, other than for the central bank to abandon short term interest rate management, which is non-viable as policy.

LikeLike

JKH, 1st sentence: “surfed” or “suffered?” 😀

LikeLike

David,

The heading to this set piece is:

“Competitive Devaluation Plus Monetary Expansion Does Create a Free Lunch”

The heading to Frances Coppola’s response is “Competitive Devaluation is not a Free Lunch”.

Firstly, your heading includes the words “Plus Monetary Expansion” while Frances’s does not. Do you think you are both talking about the same thing?

Secondly, how does this monetary expansion come about? Is it deliberate CB policy? If it is, then is the net positive effect on all concerned not due to the devaluation but the monetary expansion? It would seem that, without monetary expansion, competitive devaluation turns into competitive deflation, which seems to have been the 1930s experience?

The Hawtrey extracts say that the British leaving gold was accompanied by BoE tightening which caused the price level to fall. So how was the British leaving gold of benefit to them given subsequent competitive devaluations?

Hawtrey elsewhere says that the primary benefit is to raise the price level relative to wages. What about the income effect of falling real wage incomes?

Hawtrey also talks of a competitive return to equilibrium. What was out of equilibrium?

One of the problems in reading your various set pieces and posts and Hawtrey’s extracts is that it is sometimes difficult to discern whether devaluation in general is being discussed or whether the experience of Britain going off gold and the actions of the BoE are being discussed.

LikeLike

Tom,

Either or both.

LikeLike

“if the Bank of England for example prints pounds and purchases dollars, those dollars are the property of the BoE. I.e. those dollars do not get into the private sector.”

No but the Pounds do via “external” injection. Someone bought those Pounds. What happened to them?

LikeLike