A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a post chiding John Taylor for his habitual verbal carelessness. As if that were not enough, Taylor, in a recent talk at the IMF, appearing on a panel on monetary policy with former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and the former head of the South African central bank, Gill Marcus, extends his trail of errors into new terrain: historical misstatement. Tony Yates and Paul Krugman have already subjected Taylor’s talk to well-deserved criticism for its conceptual confusion, but I want to focus on the outright historical errors Taylor blithely makes in his talk, a talk noteworthy, apart from its conceptual confusion and historical misstatements, for the incessant repetition of the meaningless epithet “rules-based,” as if he were a latter-day Homeric rhapsodist incanting a sacred text.

Taylor starts by offering his own “mini history of monetary policy in the United States” since the late 1960s.

When I first started doing monetary economics . . ., monetary policy was highly discretionary and interventionist. It went from boom to bust and back again, repeatedly falling behind the curve, and then over-reacting. The Fed had lofty goals but no consistent strategy. If you measure macroeconomic performance as I do by both price stability and output stability, the results were terrible. Unemployment and inflation both rose.

What Taylor means by “interventionist,” other than establishing that he is against it, is not clear. Nor is the meaning of “bust” in this context. The recession of 1970 was perhaps the mildest of the entire post-World War II era, and the 1974-75 recession was certainly severe, but it was largely the result of a supply shock and politically imposed wage and price controls exacerbated by monetary tightening. (See my post about 1970s stagflation.) Taylor talks about the Fed’s lofty goals, but doesn’t say what they were. In fact in the 1970s, the Fed was disclaiming responsibility for inflation, and Arthur Burns, a supposedly conservative Republican economist, appointed by Nixon to be Fed Chairman, actually promoted what was then called an “incomes policy,” thereby enabling and facilitating Nixon’s infamous wage-and-price controls. The Fed’s job was to keep aggregate demand high, and, in the widely held view at the time, it was up to the politicians to keep business and labor from getting too greedy and causing inflation.

Then in the early 1980s policy changed. It became more focused, more systematic, more rules-based, and it stayed that way through the 1990s and into the start of this century.

Yes, in the early 1980s, policy did change, and it did become more focused, and for a short time – about a year and a half – it did become more rules-based. (I have no idea what “systematic” means in this context.) And the result was the sharpest and longest post-World War II downturn until the Little Depression. Policy changed, because, under Volcker, the Fed took ownership of inflation. It became more rules-based, because, under Volcker, the Fed attempted to follow a modified sort of Monetarist rule, seeking to keep the growth of the monetary aggregates within a pre-determined target range. I have explained in my book and in previous posts (e.g., here and here) why the attempt to follow a Monetarist rule was bound to fail and why the attempt would have perverse feedback effects, but others, notably Charles Goodhart (discoverer of Goodhart’s Law), had identified the problem even before the Fed adopted its misguided policy. The recovery did not begin until the summer of 1982 after the Fed announced that it would allow the monetary aggregates to grow faster than the Fed’s targets.

So the success of the Fed monetary policy under Volcker can properly be attributed to a) to the Fed’s taking ownership of inflation and b) to its decision to abandon the rules-based policy urged on it by Milton Friedman and his Monetarist acolytes like Alan Meltzer whom Taylor now cites approvingly for supporting rules-based policies. The only monetary policy rule that the Fed ever adopted under Volcker having been scrapped prior to the beginning of the recovery from the 1981-82 recession, the notion that the Great Moderation was ushered in by the Fed’s adoption of a “rules-based” policy is a total misrepresentation.

But Taylor is not done.

Few complained about spillovers or beggar-thy-neighbor policies during the Great Moderation. The developed economies were effectively operating in what I call a nearly international cooperative equilibrium.

Really! Has Professor Taylor, who served as Under Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs ever heard of the Plaza and the Louvre Accords?

The Plaza Accord or Plaza Agreement was an agreement between the governments of France, West Germany, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to depreciate the U.S. dollar in relation to the Japanese yen and German Deutsche Mark by intervening in currency markets. The five governments signed the accord on September 22, 1985 at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. (“Plaza Accord” Wikipedia)

The Louvre Accord was an agreement, signed on February 22, 1987 in Paris, that aimed to stabilize the international currency markets and halt the continued decline of the US Dollar caused by the Plaza Accord. The agreement was signed by France, West Germany, Japan, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. (“Louvre Accord” Wikipedia)

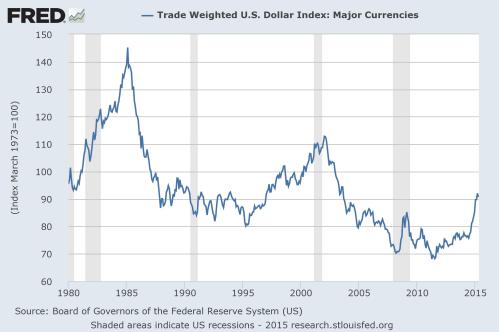

The chart below shows the fluctuation in the trade weighted value of the US dollar against the other major trading currencies since 1980. Does it look like there was a nearly international cooperative equilibrium in the 1980s?

But then there was a setback. The Fed decided to hold the interest rate very low during 2003-2005, thereby deviating from the rules-based policy that worked well during the Great Moderation. You do not need policy rules to see the change: With the inflation rate around 2%, the federal funds rate was only 1% in 2003, compared with 5.5% in 1997 when the inflation rate was also about 2%.

Well, in 1997 the expansion was six years old and the unemployment rate was under 5% and falling. In 2003, the expansion was barely under way and unemployment was rising above 6%.

I could provide other dubious historical characterizations that Taylor makes in his talk, but I will just mention a few others relating to the Volcker episode.

Some argue that the historical evidence in favor of rules is simply correlation not causation. But this ignores the crucial timing of events: in each case, the changes in policy occurred before the changes in performance, clear evidence for causality. The decisions taken by Paul Volcker came before the Great Moderation.

Yes, and as I pointed out above, inflation came down when Volcker and the Fed took ownership of the inflation, and were willing to tolerate or inflict sufficient pain on the real economy to convince the public that the Fed was serious about bringing the rate of inflation down to a rate of roughly 4%. But the recovery and the Great Moderation did not begin until the Fed renounced the only rule that it had ever adopted, namely targeting the rate of growth of the monetary aggregates. The Fed, under Volcker, never even adopted an explicit inflation target, much less a specific rule for setting the Federal Funds rate. The Taylor rule was just an ex post rationalization of what the Fed had done by instinct.

Another point relates to the zero bound. Wasn’t that the reason that the central banks had to deviate from rules in recent years? Well it was certainly not a reason in 2003-2005 and it is not a reason now, because the zero bound is not binding. It appears that there was a short period in 2009 when zero was clearly binding. But the zero bound is not a new thing in economics research. Policy rule design research took that into account long ago. The default was to move to a stable money growth regime not to massive asset purchases.

OMG! Is Taylor’s preferred rule at the zero lower bound the stable money growth rule that Volcker tried, but failed, to implement in 1981-82? Is that the lesson that Taylor wants us to learn from the Volcker era?

Some argue that rules based policy for the instruments is not needed if you have goals for the inflation rate or other variables. They say that all you really need for effective policy making is a goal, such as an inflation target and an employment target. The rest of policymaking is doing whatever the policymakers think needs to be done with the policy instruments. You do not need to articulate or describe a strategy, a decision rule, or a contingency plan for the instruments. If you want to hold the interest rate well below the rule-based strategy that worked well during the Great Moderation, as the Fed did in 2003-2005, then it’s ok as long as you can justify it at the moment in terms of the goal.

This approach has been called “constrained discretion” by Ben Bernanke, and it may be constraining discretion in some sense, but it is not inducing or encouraging a rule as a “rules versus discretion” dichotomy might suggest. Simply having a specific numerical goal or objective is not a rule for the instruments of policy; it is not a strategy; it ends up being all tactics. I think the evidence shows that relying solely on constrained discretion has not worked for monetary policy.

Taylor wants a rule for the instruments of policy. Well, although Taylor will not admit it, a rule for the instruments of policy is precisely what Volcker tried to implement in 1981-82 when he was trying — and failing — to target the monetary aggregates, thereby driving the economy into a rapidly deepening recession, before escaping from the positive-feedback loop in which he and the economy were trapped by scrapping his monetary growth targets. Since 2009, Taylor has been calling for the Fed to raise the currently targeted instrument, the Fed Funds rate, even though inflation has been below the Fed’s 2% target almost continuously for the past three years. Not only does Taylor want to target the instrument of policy, he wants the instrument target to preempt the policy target. If that is not all tactics and no strategy, I don’t know what is.

i like reading you because you often enlighten me with lost and wayside historical points of view…i think you should take this as evidence that you are in the minority (potentially even among your readership) and should make more of an effort in interpreting what people have to say and write when they use words like “few”…there is always a context in which people speak and write, so bludgeoning people with ironic ad hominems just highlights your own intellectual blindspots….

LikeLike

LAL, Thanks for your comment. I’m happy to hear that you find what I write enlightening, at least sometimes. I gather that you are not so enthusiastic about this post, but your comment is a bit too indirect for me to figure out what you are taking exception to.

LikeLike

well in this case…i take exception to…basically everything…so i chose to keep it somewhat vague…

by the word “few” i meant in Taylor’s quote “Few complained about spillovers or beggar-thy-neighbor policies during the Great Moderation.”… from the article you either do or do not agree with that statement, you definitely don’t agree about the international cooperative equilibrium. but if Taylor believes in both propositions, shouldn’t this indicate some connection between the two? and if so doesn’t it suggest that there is probably some body of evidence that is not so easily refuted by your historical facts and one graph?

i can go on an on but i am probably just taking out my frustration at krugman’s reading comprehension problems on you…

LikeLike

David,

“The Fed, under Volcker, never even adopted an explicit inflation target, much less a specific rule for setting the Federal Funds rate.”

Yes they did, and it was given to them in 1978 by Congress:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humphrey%E2%80%93Hawkins_Full_Employment_Act

“The Act set specific numerical goals for the President to attain. By 1983, unemployment rates should be not more than 3% for persons aged 20 or over and not more than 4% for persons aged 16 or over, and inflation rates should not be over 4%. By 1988, inflation rates should be 0%. The Act allows Congress to revise these goals over time.”

Also of note –

“The Act explicitly instructs the nation to strive toward four ultimate goals: full employment, growth in production, price stability, and balance of trade and budget.”

LikeLike

(In the 1970’s) “The Fed’s job was to keep aggregate demand high, and, in the widely held view at the time, it was up to the politicians to keep business and labor from getting too greedy and causing inflation.”

Yes. IIRC that was the mainstream view at the time. Monetary (and fiscal) policy should be used to target low unemployment, and price and/or wage controls should be used as needed to control inflation. God how times change.

But I think you should credit Milton Friedman for doing the most to change that view. “Monetarism” was first and foremost the view that central banks, rather than “incomes policy”, can control inflation and should control inflation. Which was heresy at the time, but orthodoxy now. The k% rule was secondary.

LikeLike

Nick Rowe,

I’m not sure that’s accurate regarding policymakers, rather than economists. Edward Nelson and some others have done a lot of good research on UK and US macroeconomic policy in the Great Inflation. It’s true that they thought that things like incomes policies had a big role to play, but this was because they had a nonmonetary view of inflation in the context of increasing unemployment. Their overall view was an output-gap type view, but with a roughly horizontal SRAS curve and a cost-push view of inflation whilst the economy is on the left of the LRAS curve. The Phillips Curve view does not seem to have been on policymakers minds during this period, and the nonmonetary views of inflation were seen as an alternative in order to respond to the phenomenon of stagflation from the late 1960s onwards.

(You still come across this sort of thinking in internet Keynesians who haven’t had the benefit of reading a Keynesian textbook: they are thinking about the economy with a (roughly) horizontal SRAS curve, and so have an on/off approach to demand-pull inflation.)

Nelson argues persuasively that UK/US policymakers kept on misestimating outputg gaps in the 1970s, got better in the 1980s, and by the 1990s had dropped both the nonmonetary view of inflation and the accomponaying horizontal SRAS curve.

I recommend most of what Nelson has written, especially his novella on “Britain’s Rocky Road to Economic Stability”-

https://ideas.repec.org/e/pne58.html

LikeLike

David Glasner,

I like this post. Maybe the tone could be modified a bit (though it’s hard when people get it wrong in such consequential ways!) but I do appreciate a lot of the historical analysis. There’s an interesting parallel to be drawn from the UK’s early 1980s experience (a fairly straight and rapid disinflation from 1981-1984) and the US early 1980s experience which seems to have been all over the place, e.g. NGDP expanded very rapidly through the first 3/4s of 1981.

LikeLike

I started to work as an economist when Volcker arrived at the FED. I had to read a lot of papers in English, trying to explain this change in strategy. I remember that the new theories failed in practice, and that those papers was trying to justify the failure redefining again and again the tactic with justifications ex post. It was fun. David tells it exactly how I remember it. Of course, things have changed. But it seems that Theory continues to be “Behind the curve”, and that monetary policy is still more art than science. Rule versus discretion is a false dilemma.

LikeLike

Volcker only “succeeded” because he abandoned rules based policy. Otherwise, he would have totally destroyed the economy.

Arguably he quite misunderstand the relationship between bank reserves, monetary aggregates, and inflation. (He should have read somebody like Tobin regarding the farce of the money multiplier.) He was not only forced to abandon rules based monetary aggregate targeting, but to replace it with discretionary fed funds rate management – in pursuit of the ultimate policy goal. A failure of rules based targeting and of monetarism.

LikeLike

Yes, more or less I agree with that. But I think that we are yet behind the curve. We have no answers for a lot of questions. Manly in the financial aspects that distorted the relation between money and real economy.

LikeLike

David–I think you are a little harsh on John Taylor. He is a GOP’er, and wants tight money now, to get the Donks out of office, Bring in a GOP Prezzy, and he will loosen up. So he is not all bad.

Anyways, “Economic policies and actions in the Reagan administration,” was a paper produced by Allan Meltzer, who worked in the Reagan White House, CEA. And Meltzer said the Reagan Administration did not have a monetary, or fiscal, or regulatory policy.

Meltzer says:

“Uncertainty and lack of a coherent monetary policy were not limited to 1981-82. During the years 1984-87, the Reagan administration shifted from a freely fluctuating exchange rate to encouraging dollar devaluation first by talk and then, in 1986, by increasing money growth. These actions were followed by a decision at the Louvre in January 1987 to set a band for the exchange rate against principal currencies. Within a few months, the dollar was overvalued relative to the agreed-upon rates, so maintenance of the band required increased money growth in Germany and Japan and lower money growth in the United States. The band required higher interest rates. Between July and October 1987 interest rates on long-term U.S. government bonds increased approximately 25 percent (from 8 1/2% to about 10 1/2%). When anticipations of further increases in interest rates contributed to a rather dramatic decline of prices on the world’s stock exchanges, the administration shifted its position again. The dollar declined about 8 to 10 percent below the presumed bottom of the previous band.

It is difficult to find a consistent pattern, much less a coherent policy, in these shifts within less than one year from efforts to force devaluation by raising money growth and lowering market interest rates to a program of stabilizing exchange rates, lowering money growth, and raising interest rates and then to a program of lowering interest rates and allowing the dollar to fall. The shifts suggest an extremely short-term focus….” (boldface added.)

Of Reagan’s fiscal policy, Meltzer says,

“Why did the Reagan administration choose to run deficits that are large relative to previous peacetime experience in the United States? One possibility is that the deficits were not anticipated. This is improbable….”

Of Reagan’s regulatory record, Meltzer nearly resorts to profanity, but think trade protection and milk-price scandal.

–30–

Today, it is required (in right-wing circles) to call Reagan an inflation-figter and allied with Volcker. In fact the Reaganauts often plotted against Volcker, who was originally a Carter appointee.

Inflation did calm down in the 1990s, and perhaps the Fed and fiscal policy were then in tune, and dare I say that was the Rubin-Clinton years.

All of this says little about monetary policy today, which I think should again target growth more than inflation, although I think Market Monetarism is fine too, and I even would accept a 2.5% to 3.5% IT band, ala RBA.

BTW, I would like to see the inimitable David Glasner talk about the use of cash in high-tax developed nations that look to be going to perma-deflation ZLB zero-inflation land.

Use of cash is exploding, and has been very high in Japan for a long time.

Mr. Tax Man is frustrated–but it raises serious questions about whether a zero inflation or deflation economy is sustainable in the modern era.

There are powerful economic incentives to conduct transactions in cash when taxes are high–and when people store boodles of appreciating cash anyway…..

LikeLike

Sorry that these responses are so late in coming, but I didn’t want to just ignore them.

LAL, Taylor may have some body of evidence that he is thinking of, but I am just commenting on what I saw.

Frank, Interesting quote, but I am not sure whether the Humphrey-Hawkins number was ever considered binding in any way as opposed to being some sort of aspirational goal. I mean Humphrey-Hawkins also contained statements about a zero budget deficit and a zero trade deficit. Does (or did) anyone consider those targets binding?

Nick, I do credit Friedman with making an important contribution towards getting people to accept that the price level is largely under the control of the monetary authority. That was mainly a propagandistic success (no small thing by the way) not an analytical contribution.

W. Peden, Thanks for your interesting reconstruction of Keynesian thinking in the 1970s as well as the link to Nelson. Glad that you liked the post.

Miguel, It’s reassuring that your recollections coincide with mine. I agree that the rules versus discretion dichotomy is way overplayed.

JKH, I agree, at least if rules-based-policy is understood in Taylor’s terms. Nice to see that we are on the same side for a change.

Benjamin, If I am being too harsh on Taylor, it’s because I am taking him at his word. In giving him a free pass, you are basically calling him a hypocrite. Is that any better? And I agree that Reagan was far from being a free-market stalwart as his right-wing admirers like to portray him. But in politics, everything is relative. Taylor is purporting to speak as an economist, not a politician, and that’s how I am evaluating him.

LikeLike

David,

“Frank, Interesting quote, but I am not sure whether the Humphrey-Hawkins number was ever considered binding in any way as opposed to being some sort of aspirational goal.”

I presume you to mean “binding” in terms of a condition of employment – central banker you must hit these goals or consider yourself terminated. Then yes, I would agree, Congress did not go so far as to put the central bank’s or the President’s feet to the fire.

But Congress did feel the need to introduce and pass legislation giving specific goals to be met. And so those goals did carry the weight of law.

It wasn’t like Congress had a giant prayer meeting asking for divine intervention to steer the economy back onto course.

The extent to which an individual could be prosecuted for violations of the Humphrey Hawkins Act was never tested to my knowledge, and the stipulation that a balanced budget be reached may have been ruled Unconstitutional because achieving that goal would require that taxation and spending decisions be ceded to the Executive Branch of government.

LikeLike

Frank, Well if we adopt a zero to ten scale with zero representing your giant prayer meeting and ten representing making failure to meet the HH goals a punishable offense (high crime or misdemeanor), I would not give the HH goals more than a one. I think they were pretty much forgotten before the ink was dry.

LikeLike

David,

“I think they were pretty much forgotten before the ink was dry.”

You are entitled to your own thoughts but you might at least check that the U. S. did run a budget surplus (1997-2002) and did run a current account surplus for a brief period in 1991 (though not a trade surplus).

And so, perhaps, while HH was not legally binding as a punishable offense, it’s “aspirational goals” did shape economic policy well into the future.

LikeLike