At its meeting today, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided . . . , well, decided not to decide. Faced with a feeble US economic recovery showing clear signs of getting weaker still, and a perilous economic situation in Europe poised to spin out of control into a full-blown financial crisis, the FOMC opted to continue the status quo, prolonging its so-called Operation Twist in which the Fed is liquidating its holdings of short-dated Treasuries and replacing them with longer-dated Treasuries, on the theory that changing the maturity structure of the Fed’s balance sheet will reduce long-term interest rates, thereby providing some further incentive for long-term borrowing, as if the problem holding back a recovery were long-term nominal interest rates that are not low enough.

What I found most interesting in today’s statement was the FOMC’s assessment of inflation. In the opening paragraph of its statement, the FOMC states:

Inflation has declined, mainly reflecting lower prices of crude oil and gasoline, and longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

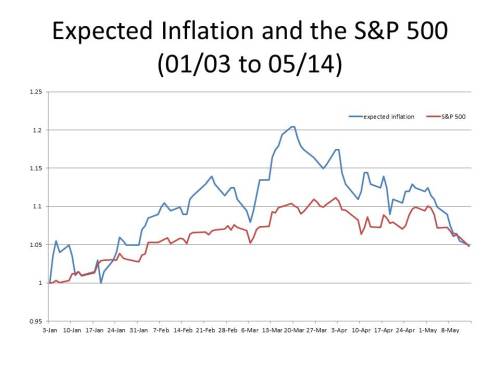

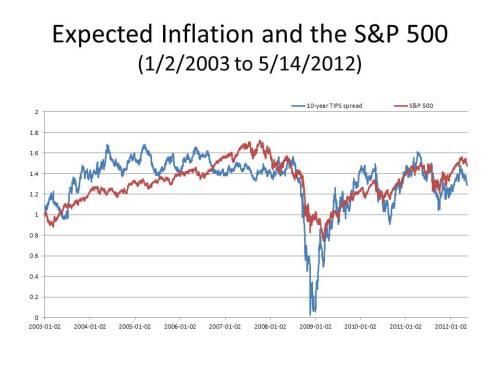

What is the basis for the FOMC’s statement that inflation expectations are stable? Does the FOMC not take seriously the estimate of inflation expectations just published by the Cleveland Fed showing that inflation expectations over a 10-year time horizon are at an all-time low of 1.19% and the expectation for the next 12 months is 0.6%, the lowest since March 2009 when the stock market reached its post-crisis low? And the FOMC’s April projection for PCE inflation in 2012 was in a range 1.9 to 2.0%; its current projection is now 1.2 to 1.7%. In contrast to 2008, when the FOMC was in a tizzy about inflation expectations becoming unanchored because of rapidly rising food and energy prices, the FOMC seems remarkably calm and unperturbed about a 0.3% fall in headline inflation in May.

Then in the next paragraph the FOMC makes another — shall we say, puzzling — statement:

The Committee anticipates that inflation over the medium term will run at or below the rate that it judges most consistent with its dual mandate.

So the FOMC admits that inflation is likely to be less than its own inflation target. Let’s be sure that we understand this. The economy is weakening, growth is slowing, unemployment, after nearly four years above 8 percent, is once again rising, and the Fed’s own expectation of the inflation rate for 2012 is well below the FOMC target. And what is the FOMC response? Steady as you go.

In a news story about the FOMC decision, Marketwatch reporter Steve Goldstein writes:

The Federal Reserve on Wednesday softened its growth and inflation forecasts over the next three years, as the central bank said the unemployment rate will hold above 8% through the end of 2012. The Fed also cut its inflation forecast down aggressively, to between 1.2% and 1.7% this year, as opposed to its forecast in April between 1.9% and 2%. The central bank targets 2% inflation over the medium term, so the reduced inflation forecast is likely to ratchet up expectations of additional central bank easing, possibly as soon as August. The Fed’s forecast for growth this year is down to a range of 1.9% to 2.4%, down from 2.4% to 2.9% in April — and its April 2011 forecast that 2012 growth would range between 3.5% and 4.2%. Also of note, it appears that the two newest voters, Jerome Powell and Jeremy Stein, are among the most dovish; the most recent breakdown of when the right time to raise hikes shows the only change is in 2015, which now has six members in that camp, up from four in April. Powell and Stein were recently sworn in as Fed governors.

So the optimistic take on all this is that the FOMC has set the stage for taking aggressive action at its next meeting. Since bottoming out last week, stock prices recovered, apparently in expectation of easing by the Fed. Today’s announcement is not what the market was hoping for, but there are at least signs that the FOMC will take action soon. In our desperation, we have been reduced to grasping at straws.