No question about it Charles Schwab is a very smart man, and performed a great service by making the stock brokerage business a lot more competitive than it used to be before he came on the scene. But does that qualify him as an expert on monetary policy? Not necessarily. But I am not sure what qualifies anyone as an expert on monetary policy, so I don’t want to suggest that a lack of credentials disqualifies Mr. Schwab, or anyone else, even Ron Paul, from offering an opinion on monetary policy. But in his op-ed piece in today’s Wall Street Journal, Mr. Schwab certainly gets off to a bad start when he says:

We’re now in the 37th month of central government manipulation of the free-market system through the Federal Reserve’s near-zero interest rate policy. Is it working?

Thirty-seven months ago, the US and the world economy were in a state of crisis, with stock prices down almost 50 percent from their level six months earlier. To suggest that taking steps to alleviate that crisis constitutes government manipulation of the free-market system is clearly an ideologically loaded statement, acceptable to a tiny sliver of professional economists, lacking any grounding in widely accepted economic principles. The tiny sliver of economists who would agree with Mr. Schwab’s assessment may just be right — though I think they are wrong — but on as controversial a topic as this, it bespeaks a certain arrogance to assert as simple fact what is in fact the view of a tiny, and not especially admired, minority of the economics profession. (I don’t mean the preceding sentence to be construed as in any way an attack on economists favoring a free-market monetary system. I know and admire a number of economists who take that view, I am just emphasizing how unorthodox that view is considered by most of the profession.)

It’s actually a pity that Mr. Schwab chose to couch his piece in such ideological terms, because much of what he says makes a lot of sense. For example:

Business and consumer loan demand remains modest in part because there’s no hurry to borrow at today’s super-low rates when the Fed says rates will stay low for years to come. Why take the risk of borrowing today when low-cost money will be there tomorrow?

Many of us in the Market Monetarist camp already have pointed out that the Fed’s low interest policy is a double-edged sword, because the policy, as Mr. Schwab correctly points out, tends to reinforce self-fulfilling market pessimism about future economic conditions. The problem arises because the economy now finds itself in what Ralph Hawtrey called a “credit deadlock.” In a credit deadlock, pessimistic expectations on the part of traders, consumers and bankers is so great that reducing interest rates does little to stimulate investment spending by businesses, consumer spending by households, and lending by banks. While recognizing the obstacles to the effectiveness of monetary policy conducted in terms of the bank rate, Hawtrey argued that there are alternative instruments at the disposal of the monetary authorities by which to promote recovery.

Mr. Schwab goes on to provide a good description of the symptoms of a credit-deadlock except that he attributes the cause of the deadlock entirely to Fed actions rather than to an underlying pessimism that preceded them.

The Fed policy has resulted in a huge infusion of capital into the system, creating a massive rise in liquidity but negligible movement of that money. It is sitting there, in banks all across America, unused. The multiplier effect that normally comes with a boost in liquidity remains at rock bottom. Sufficient capital is in the system to spur growth—it simply isn’t being put to work fast enough.

He makes a further astute observation about the ambiguous effects of the Fed’s announcement that it is planning to keep interest rates at current levels through 2014.

The Fed’s Jan. 25 statement that it would keep short-term interest rates near zero until at least late 2014 is sending a signal of crisis, not confidence. To any potential borrower, the Fed’s policy is saying, in effect, the economy is still in critical condition, if not on its deathbed. You can’t keep a patient on life support and expect people to believe he’s gotten better.

Mr. Schwab then argues that all that is required to cure the credit deadlock is for the Fed to declare victory and begin a strategic withdrawal from the field of battle.

This is what investors, business people and everyday Americans should hope to hear from Mr. Bernanke after the next Federal Open Market Committee meeting:

The Federal Reserve used its emergency powers effectively and appropriately when the financial crisis began, but it is very clear that the economy is on the mend and that the benefit of inserting massive liquidity into the economy has passed. We will let interest rates move where natural markets take them. Our experiment with market manipulation will stop beginning today. Effective immediately, we will begin to move Fed rate policy toward its natural longer-term equilibrium. With the extremes of the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 long behind us, free markets are the best means to create stable growth. Our objective is now to let the system work on its own. It is now healthy enough to do just that. We hope today’s announcement does two things immediately: first, that it highlights our confidence—supported by the data—that the U.S. economy is out of its emergency state and in the process of mending, and second, that it reflects our belief that the Federal Reserve’s role in economic policy is limited.

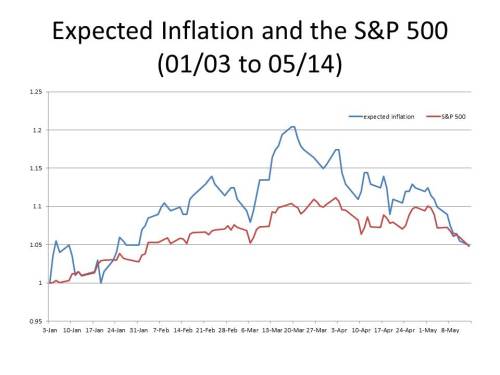

What Mr. Schwab fails to note is that the value of money (its purchasing power at any moment) and the rate of inflation cannot be determined in a free market. That is the job of the monetary authority. Aside from the tiny sliver of the economics profession that believes that the value of money ought to be determined by some sort of free-market process, that responsibility is now taken for granted. The problem at present is that the expected future price level (or the expected rate of growth in nominal GDP) is below the level consistent with full employment. The problem with Fed policy is not that it is keeping rates too low, but that it is content to allow expectations of inflation (or expectations of future growth in nominal GDP) to remain below levels necessary for a strong recovery. The Reagan recovery, as I noted recently, is hailed as a model for the Obama administration and the Fed by conservative economists like John Taylor, and the Wall Street Journal editorial page, and presumably by Mr. Charles Schwab himself. The salient difference between our anemic pseudo recovery and the Reagan recovery is that inflation averaged 3.5 to 4 percent and nominal GDP growth in the Reagan recovery exceeded 10 percent for 5 consecutive quarters (from the second quarter of 1983 to the second quarter of 1984). The table below shows the rate of NGDP growth during the last six years of the Reagan administration from 1983 through 1988. This is why, as I have explained many times on this blog (e.g., here and here)and in this paper, since the early days of the Little Depression in 2008, the stock market has loved inflation.

Here’s how Hawtrey put it in his classic A Century of Bank Rate:

The adequacy of these small changes of Bank rate, however, depends upon psychological reactions. The vicious circle of expansion or contraction is partly, but not exclusively, a psychological phenomenon. It is the expectation of expanding demand that leads to a creation of credit and so causes demand to expand; and it is the expectation of flagging demand that deters borrowers and so causes demand to flag. . . . The vicious circle may in either case have any degree of persistence and force within wide limits; it may be so mild as to be easily counteracted, or it may be so violent as to require heroic measures. (p. 275)

Therefore the monetary authorities of a country which has been cut loose from any metallic or international standard find themselves compelled to some degree to regulate the foreign exchanges, either by buying and selling foreign currencies or gold, or (deplorable alternative) by applying exchange control. Thus at any moment the problem of monetary policy presents itself as a choice between a modification of the rate of exchange credit an adjustment of the credit system through Bank rate. And if the modification of the rate of exchange is such as to favour stable activity, the need for a change in Bank rate may be all the less. When a credit deadlock has thrown Bank rate out of action, modification of rates of exchange may be found to be the most valuable and effective instruments of monetary policy. (p. 277)

There is thus no doubt that the Fed could achieve (within reasonable margins of error) any desired price level or rate of growth in nominal GDP by announcing its target and expressing its willingness to drive down the dollar exchange rate in terms of one or several currencies until its price level or NGDP target were met. That, not abdication of its responsibility, is the way the Fed can strengthen the ever so faint signs of a budding recovery (remember those green shoots?).