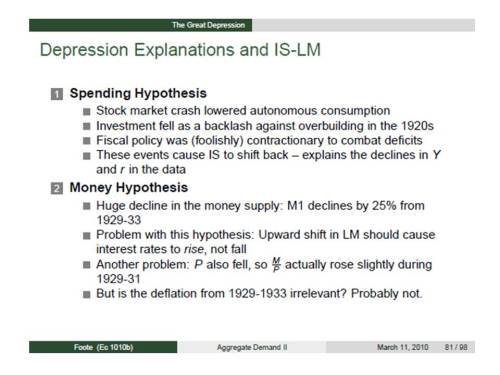

Last Friday, Scott Sumner posted a diatribe against the IS-LM triggered by a set of slides by Chris Foote of Harvard and the Boston Fed explaining how the effects of monetary policy can be analyzed using the IS-LM framework. What really annoys Scott is the following slide in which Foote compares the “spending (aka Keynesian) hypothesis” and the “money (aka Monetarist) hypothesis” as explanations for the Great Depression. I am also annoyed; whether more annoyed or less annoyed than Scott I can’t say, interpersonal comparisons of annoyance, like interpersonal comparisons of utility, being beyond the ken of economists. But our reasons for annoyance are a little different, so let me try to explore those reasons. But first, let’s look briefly at the source of our common annoyance.

The “spending hypothesis” attributes the Great Depression to a sudden collapse of spending which, in turn, is attributed to a collapse of consumer confidence resulting from the 1929 stock-market crash and a collapse of investment spending occasioned by a collapse of business confidence. The cause of the collapse in consumer and business confidence is not really specified, but somehow it has to do with the unstable economic and financial situation that characterized the developed world in the wake of World War I. In addition there was, at least according to some accounts, a perverse fiscal response: cuts in government spending and increases in taxes to keep the budget in balance. The latter notion that fiscal policy was contractionary evokes a contemptuous response from Scott, more or less justified, because nominal government spending actually rose in 1930 and 1931 and spending in real terms continued to rise in 1932. But the key point is that government spending in those days was too meager to have made much difference; the spending hypothesis rises or falls on the notion that the trigger for the Great Depression was an autonomous collapse in private spending.

The “spending hypothesis” attributes the Great Depression to a sudden collapse of spending which, in turn, is attributed to a collapse of consumer confidence resulting from the 1929 stock-market crash and a collapse of investment spending occasioned by a collapse of business confidence. The cause of the collapse in consumer and business confidence is not really specified, but somehow it has to do with the unstable economic and financial situation that characterized the developed world in the wake of World War I. In addition there was, at least according to some accounts, a perverse fiscal response: cuts in government spending and increases in taxes to keep the budget in balance. The latter notion that fiscal policy was contractionary evokes a contemptuous response from Scott, more or less justified, because nominal government spending actually rose in 1930 and 1931 and spending in real terms continued to rise in 1932. But the key point is that government spending in those days was too meager to have made much difference; the spending hypothesis rises or falls on the notion that the trigger for the Great Depression was an autonomous collapse in private spending.

But what really gets Scott all bent out of shape is Foote’s commentary on the “money hypothesis.” In his first bullet point, Foote refers to the 25% decline in M1 between 1929 and 1933, suggesting that monetary policy was really, really tight, but in the next bullet point, Foote points out that if monetary policy was tight, implying a leftward shift in the LM curve, interest rates should have risen. Instead they fell. Moreover, Foote points out that, inasmuch as the price level fell by more than 25% between 1929 and 1933, the real value of the money supply actually increased, so it’s not even clear that there was a leftward shift in the LM curve. You can just feel Scott’s blood boiling:

What interests me is the suggestion that the “money hypothesis” is contradicted by various stylized facts. Interest rates fell. The real quantity of money rose. In fact, these two stylized facts are exactly what you’d expect from tight money. The fact that they seem to contradict the tight money hypothesis does not reflect poorly on the tight money hypothesis, but rather the IS-LM model that says tight money leads to a smaller level of real cash balances and a higher level of interest rates.

To see the absurdity of IS-LM, just consider a monetary policy shock that no one could question—hyperinflation. Wheelbarrows full of billion mark currency notes. Can we all agree that that would be “easy money?” Good. We also know that hyperinflation leads to extremely high interest rates and extremely low real cash balances, just the opposite of the prediction of the IS-LM model. In contrast, Milton Friedman would tell you that really tight money leads to low interest rates and large real cash balances, exactly what we do see.

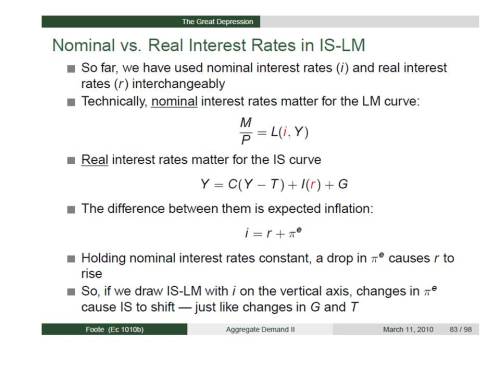

Scott is totally right, of course, to point out that the fall in interest rates and the increase in the real quantity of money do not contradict the “money hypothesis.” However, he is also being selective and unfair in making that criticism, because, in two slides following almost immediately after the one to which Scott takes such offense, Foote actually explains that the simple IS-LM analysis presented in the previous slide requires modification to take into account expected deflation, because the demand for money depends on the nominal rate of interest while the amount of investment spending depends on the real rate of interest, and shows how to do the modification. Here are the slides:

Thus, expected deflation raises the real rate of interest thereby shifting the IS curve to the left while leaving the LM curve where it was. Expected deflation therefore explains a fall in both nominal and real income as well as in the nominal rate of interest; it also explains an increase in the real rate of interest. Scott seems to be emotionally committed to the notion that the IS-LM model must lead to a misunderstanding of the effects of monetary policy, holding Foote up as an example of this confusion on the basis of the first of the slides, but Foote actually shows that IS-LM can be tweaked to accommodate a correct understanding of the dominant role of monetary policy in the Great Depression.

Thus, expected deflation raises the real rate of interest thereby shifting the IS curve to the left while leaving the LM curve where it was. Expected deflation therefore explains a fall in both nominal and real income as well as in the nominal rate of interest; it also explains an increase in the real rate of interest. Scott seems to be emotionally committed to the notion that the IS-LM model must lead to a misunderstanding of the effects of monetary policy, holding Foote up as an example of this confusion on the basis of the first of the slides, but Foote actually shows that IS-LM can be tweaked to accommodate a correct understanding of the dominant role of monetary policy in the Great Depression.

The Great Depression was triggered by a deflationary scramble for gold associated with the uncoordinated restoration of the gold standard by the major European countries in the late 1920s, especially France and its insane central bank. On top of this, the Federal Reserve, succumbing to political pressure to stop “excessive” stock-market speculation, raised its discount rate to a near record 6.5% in early 1929, greatly amplifying the pressure on gold reserves, thereby driving up the value of gold, and causing expectations of the future price level to start dropping. It was thus a rise (both actual and expected) in the value of gold, not a reduction in the money supply, which was the source of the monetary shock that produced the Great Depression. The shock was administered without a reduction in the money supply, so there was no shift in the LM curve. IS-LM is not necessarily the best model with which to describe this monetary shock, but the basic story can be expressed in terms of the IS-LM model.

So, you ask, if I don’t think that Foote’s exposition of the IS-LM model seriously misrepresents what happened in the Great Depression, why did I say at beginning of this post that Foote’s slides really annoy me? Well, the reason is simply that Foote seems to think that the only monetary explanation of the Great Depression is the Monetarist explanation of Milton Friedman: that the Great Depression was caused by an exogenous contraction in the US money supply. That explanation is wrong, theoretically and empirically.

What caused the Great Depression was an international disturbance to the value of gold, caused by the independent actions of a number of central banks, most notably the insane Bank of France, maniacally trying to convert all its foreign exchange reserves into gold, and the Federal Reserve, obsessed with suppressing a non-existent stock-market bubble on Wall Street. It only seems like a bubble with mistaken hindsight, because the collapse of prices was not the result of any inherent overvaluation in stock prices in October 1929, but because the combined policies of the insane Bank of France and the Fed wrecked the world economy. The decline in the nominal quantity of money in the US, the great bugaboo of Milton Friedman, was merely an epiphenomenon.

As Ron Batchelder and I have shown, Gustav Cassel and Ralph Hawtrey had diagnosed and explained the causes of the Great Depression fully a decade before it happened. Unfortunately, whenever people think of a monetary explanation of the Great Depression, they think of Milton Friedman, not Hawtrey and Cassel. Scott Sumner understands all this, he’s even written a book – a wonderful (but unfortunately still unpublished) book – about it. But he gets all worked up about IS-LM.

I, on the other hand, could not care less about IS-LM; it’s the idea that the monetary cause of the Great Depression was discovered by Milton Friedman that annoys the [redacted] out of me.

UPDATE: I posted this post prematurely before I finished editing it, so I apologize for any mistakes or omissions or confusing statements that appeared previously or that I haven’t found yet.

David, it´s always the “force of personality” that “gets the kudos”.! Hawtrey and Cassel´s discovery were “eclipsed” by Keynes´”force of personality (FoP)”. It took Friedman´s FoP to eclipse Keynes and allow the rediscovery of H&C´s explanation of the GD. Maybe in 20 years time people will “discover” that the GR was not the result of a financial crisis; that it was the consequence of extremely bad MP.

LikeLike

Splendid post, as usual. My friend Marcus will perhaps win the war against financial factors in GR, but he don’t convince me. On the other hand, how can we split financial and monetary problems? When we introduce expectations (rational or adaptive) financial dislocations are indisputable, I think.

Why I’m saying is that financial is the “go-between” money and real economy. Perhaps a little Keynesian, but I don’t care very much about. In any case, I agree that gold was the main actor in the GD.

LikeLike

Miguel. The Beatles “tell the tale”:

LikeLike

“On top of this, the Federal Reserve, succumbing to political pressure to stop “excessive” stock-market speculation, raised its discount rate to a near record 6.5% in early 1929, greatly amplifying the pressure on gold reserves, thereby driving up the value of gold, and causing expectations of the future price level to start dropping.”

I had heard of the IBOF before, but not about the Federal Reserve’s raising of the discount rate as explanation for a higher gold price. I don’t entirely grasp the flow from cause to effect here — any chance you can provide some more colour on the Fed’s actions and how they pushed up the price of the metal?

LikeLike

Luis, you write:

“When we introduce expectations (rational or adaptive) financial dislocations are indisputable, I think.”

Perhaps the rational for introducing expectations at all is a flawed one. Here are some alternative views: [1] and [2].

LikeLike

Louis, re: “expectations” (and related concepts, call them “X”): sometimes the concept is abused as follows by proponents:

“Concrete monetary policy actions by the CB (OMOs, QE, etc) would be more than adequate if only the CB had enough X. How much X do they have now and how much would be adequate? And can we independently observe X to test the X hypothesis? No, you can’t measure or independently test for X: you’ll know when X is sufficient when OMOs work as the text books say they should.”

A circle of logic which makes it truly irrelevant what X is. X might just as well be “je ne sais quoi.” The X hypothesis is unfalsifiable.

There exist falsifiable alternatives to the X hypothesis.

LikeLike

Marcus, You’re right, at least partially. I am just trying to do my small part to redress the imbalance of forces. Sorry, but I give Friedman no credit for allowing the rediscovery of Hawtrey and Cassel. Keynes gave Hawtrey and Cassel much more recognition than Friedman ever did.

Luis, Thanks. I think that financial factors played an important part in the Little Depression (sorry, I prefer that label to “Great Recession”). But financial factors were a background factor that made the system vulnerable to bad policy, just as allied war debts, German war reparations, and irresponsible borrowing by the German states and local governments increased the vulnerability of the world economy to deflation before the onset of the Great Depression.

JP, When a central bank increases its interest rates under the gold standard, it induces an inflow of gold, that is the equivalent of an increase in the monetary demand for gold. The nominal gold price was not changed, but the value of gold increased because of the increased monetary demand, causing the prices of goods and services measured in gold to fall.

LikeLike

Hawtrey and Cassel! They has the answers! (A tribute to the WSJ).

LikeLike

Add on: Can the Fed tighten its way to higher interest rates? As Milton Friedman noted…probably not for long. So if central bank is in or near ZLB it probably can only get to higher real rates through robust growth….

LikeLike

David,

With reference to your paragraph beginning with “The Great Depression was triggered by…”, would this be similar to your explanation of the Crash of 2008?

LikeLike

David,

“When a central bank increases its interest rates under the gold standard, it induces an inflow of gold, that is the equivalent of an increase in the monetary demand for gold. The nominal gold price was not changed, but the value of gold increased because of the increased monetary demand, causing the prices of goods and services measured in gold to fall.”

A central bank in trying to maintain a gold peg makes the promise that it will pay the same amount of currency when it buys gold and it will accept the same amount of currency when it sells gold. Obviously this is impossible under a fractional reserve banking system where the amount of currency outstanding can float independently of the total amount of gold.

An increase in the discount rate by the central bank will cause an net inflow of gold to the central bank IF and ONLY IF, banks borrow from that central bank at that higher rate, private credit either defaults or contracts, and loans payable to the central bank are required to be paid in gold.

** Remember – The FOMC was not created until 1933. The only tools the central bank had at the time were the discount rate and the reserve requirement.

In trying to hit a gold price target, the central bank can run into problems. If private individuals try to bid up the price of gold relative to currency (monetary demand for gold), the central bank must sell gold to hold the price constant. But the central bank may not have a sufficient supply to sell. A central bank can try to raise the discount rate to attract gold, but it still must find borrowers at that interest rate.

LikeLike

Correction:

An increase in the discount rate by the central bank will cause an net outflow of gold from private hands IF and ONLY IF, banks borrow from that central bank at that higher rate, private credit either defaults or contracts, and loans payable to the central bank are required to be paid in gold.

Obviously if new gold is discovered by private enterprise at the same rate that the central bank is pulling in gold via interest rate adjustment, then there is zero net outflow of gold from private hands.

Funny that you make no mention of the gold supply interruption in your analysis of the Great Depression. See:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_Rush

Notice that the pace of gold discovery slowed significantly after 1920.

LikeLike

Gold was not free during the onset of the Great Depression. You could only move gold across the Pond in 1000oz bars, which effectively took gold as money out of the hands of ordinary people and into the hands of bankers. Thus Friedman is probably right in that central bankers are responsible for turning an ordinary panic (the Crash of 1929) into a Great Depression. If gold was truly free,and allowed to enter and exit countries as it did in the 19th century, likely the Great Depression would be called the Panic of 1929 and have been over in 4 years.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia – you are standing in it!.

LikeLike