Last week I posted an item summarizing Matthew O’Brien’s article about the just-released transcripts of FOMC meetings in June, August and September of 2008. I spiced up my summary by quoting from and commenting on some of the more outrageous quotes that O’Brien culled from the transcripts, quotes showing that most of the FOMC, including Ben Bernanke, were obsessing about inflation while unemployment was rising rapidly and the economy contracting sharply. I especially singled out what I called the Gang of Four — Charles Plosser, Jeffrey Lacker, Richard Fisher, and Thomas Hoenig, the most militant inflation hawks on the FOMC — noting that despite their comprehensive misjudgments of the 2008 economic situation and spectacularly wrongheaded policy recommendations, which they have yet to acknowledge, much less apologize for, three of them (Plosser, Lacker, and Fisher) continue to serve in their Fed positions, displaying the same irrational inflation-phobia by which they were possessed in 2008. Paul Krugman also noticed O’Brien’s piece and remarked on the disturbing fact that three of the Gang of Four remain in their policy-making positions at the Fed, doing their best to keep the Fed from taking any steps that could increase output and employment.

However, Krugman went on to question the idea — suggested by, among others, me — that it was the Fed’s inflation phobia that produced the crash of 2008. Krugman has two arguments for why the Fed’s inflation phobia in 2008, however silly, did not the cause of the crash.

First, preventing the financial crisis would have taken a lot more than cutting the Fed funds rate to zero in September 2008 rather than December. We were in the midst of an epic housing bust, which was in turn causing a collapse in the value of mortgage-backed securities, which in turn was causing a collapse of confidence in financial firms. Cutting rates from very low to extremely low a few months earlier wouldn’t have stopped that collapse.

What was needed to end the run on Wall Street was a bailout — both the actual funds disbursed and the reassurance that the authorities would step in if necessary. And that wasn’t in the cards until, as Rick Mishkin observed in the transcripts, “something hit the fan.”

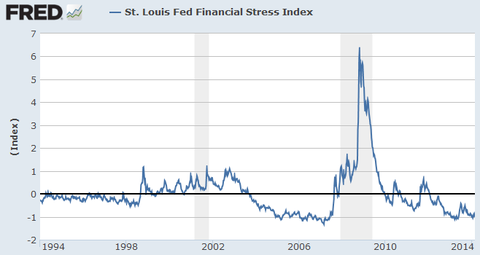

Second, even avoiding the financial panic almost surely wouldn’t have meant avoiding a prolonged economic slump. How do we know this? Well, what we actually know is that the panic was in fact fairly short-lived, ending in the spring of 2009. It doesn’t really matter which measure of financial stress you use, they all look like this:

Yet the economy didn’t come roaring back, and in fact still hasn’t. Why? Because the housing bust and the overhang of household debt are huge drags on demand, even if there isn’t a panic in the financial market.

Sorry, but, WADR, I have to disagree with Professor Krugman.

The first argument is not in my view very compelling, because the Fed’s inflation-phobia did not suddenly appear at the September 2008 FOMC meeting, or even at the June meeting, though, to be sure, its pathological nature at those meetings does have a certain breathtaking quality; it had already been operating for a long time before that. If you look at the St. Louis Fed’s statistics on the monetary base, you will find that the previous recession in 2001 had been preceded in 2000 by a drop of 3.6% in the monetary base. To promote recovery, the Fed increased the monetary base in 2001 (partly accommodating the increased demand for money characteristic of recessions) by 8.5%. The monetary base subsequently grew by 7% in 2002, 5.2% in 2003, 4.4% in 2004, 3.2% in 2005, 2.6% in 2006, and a mere 1.2% in 2007.

The housing bubble burst in 2006, but the Fed was evidently determined to squeeze inflation out of the system, as if trying to atone for its sins in allowing the housing bubble in the first place. From January to September 10, 2008, the monetary base increased by 3.3%. Again, because the demand for money typically increases in recessions, one cannot infer from the slight increase in the rate of growth of the monetary base in 2008 over 2006 and 2007 that the Fed was easing its policy stance. (On this issue, see my concluding paragraph.) The point is that for at least three years before the crash, the Fed, in its anti-inflationary zelotry, had been gradually tightening the monetary-policy screws. So it is simply incorrect to suggest that there was no link between the policy stance of the Fed and the state of the economy. If the Fed had moderated its stance in 2008 in response to ample evidence that the economy was slowing, there is good reason to think that the economy would not have contracted as rapidly as it did, starting, even before the Lehman collapse, in the third quarter of 2008, when, we now know, the economy had already begun one of the sharpest contractions of the entire post World War II era.

As for Krugman’s second argument, I believe it is a mistake to confuse a financial panic with a recession. A financial panic is an acute breakdown of the financial system, always associated with a period of monetary stringency when demands for liquidity cannot be satisfied owing to a contagious loss of confidence in the solvency of borrowers and lenders. The crisis is typically precipitated by a too aggressive tightening of monetary conditions by the monetary authority seeking to rein in inflationary pressures. The loss of confidence is thus not a feature of every business-cycle downturn, and its restoration no guarantee of a recovery. (See my post on Hawtrey and financial crises.) A recovery requires an increase aggregate demand, which is the responsibility of those in charge of monetary policy and fiscal policy. I confess to a measure of surprise that the author of End This Depression Now would require a reminder about that from me.

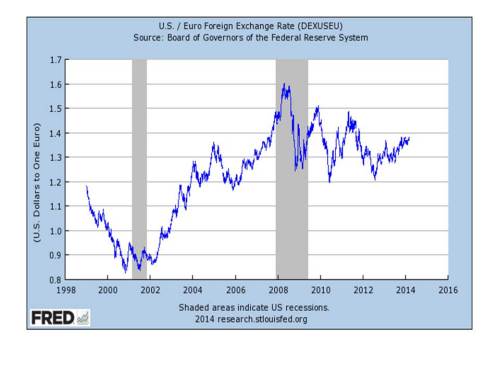

A final point. Although the macroeconomic conditions for an asset crash and financial panic had been gradually and systematically created by the Fed ever since 2006, the egregious Fed policy in the summer of 2008 was undoubtedly a major contributing cause in its own right. The magnitude of the policy error is evident in this graph from the St. Louis Fed, showing the dollar/euro exchange rate.

From April to July, the exchange rate was fluctuating between $1.50 and $1.60 per euro. In mid-July, the dollar began appreciating rapidly against the euro, rising in value to about $1.40/euro just before the Lehman collapse, an appreciation of about 12.5% in less than two months. The only comparable period of appreciation in the dollar/euro exchange rate was in the 1999-2000 period during the monetary tightening prior to the 2001 recession. But the 2008 appreciation was clearly greater and steeper than the appreciation in 1999-2000. Under the circumstances, such a sharp appreciation in the dollar should have alerted the FOMC that there was a liquidity shortage (also evidenced in a sharp increase in borrowings from the Fed) that required extraordinary countermeasures by the Fed. But the transcript of the September 2008 meeting shows that the appreciation of the dollar was interpreted by members of the FOMC as evidence that the current policy was working as intended! Now how scary is that?

From April to July, the exchange rate was fluctuating between $1.50 and $1.60 per euro. In mid-July, the dollar began appreciating rapidly against the euro, rising in value to about $1.40/euro just before the Lehman collapse, an appreciation of about 12.5% in less than two months. The only comparable period of appreciation in the dollar/euro exchange rate was in the 1999-2000 period during the monetary tightening prior to the 2001 recession. But the 2008 appreciation was clearly greater and steeper than the appreciation in 1999-2000. Under the circumstances, such a sharp appreciation in the dollar should have alerted the FOMC that there was a liquidity shortage (also evidenced in a sharp increase in borrowings from the Fed) that required extraordinary countermeasures by the Fed. But the transcript of the September 2008 meeting shows that the appreciation of the dollar was interpreted by members of the FOMC as evidence that the current policy was working as intended! Now how scary is that?

HT: Matt O’Brien

It certainly mattered a lot. And still does:

LikeLike

Another aspect of all this that doesn’t get nearly enough discussion:

Wasn’t another key triggering event in 2008 when the Fed funds rate approached 0%? At that point, the Fed became extremely cautious. It was out of its comfort zone. Recognizing the Fed’s discomfort with unconventional monetary measures, market expectations of future demand in 2010 and 2011 collapsed, right?

As Nick Rowe has said, when interest rates fall to 0%, the Fed becomes “mute.”

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/02/the-mute-king.html

Its favored steering mechanism locks up right when it needs it most: a surprise fall in NGDP.

There needs to be more discussion about the Fed’s discomfort after we fell into the “liquidity trap.” It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: if everyone believes the central bank is powerless in a “liquidity trap,” then it becomes true: the Fed is effectively powerless.

LikeLike

I pre-agreed with your assessment “the macroeconomic conditions for an asset crash and financial panic had been gradually and systematically created by the Fed ever since 2006” in a post a few days ago:

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-fed-caused-great-recession.html

Using a cheap fitted model, I figured that the Fed had *effectively* been raising interest rates since 2006 (rates wen’t down a bit in 2007, but they didn’t go down as much as they should have to keep NGDP proportional to MB). The lack of an expected rate reduction in September 2008 may have been the small noise that caused the avalanche.

LikeLike

Great post, David.

LikeLike

David,

I agree it is crucial to separate out a financial panic from a recession. However your response doesn’t really deal with the issue of house prices and monetary policy I raised in your previous post. Are you claiming that the Fed could have maintained house price growth by loosening monetary policy say from as early as say 2007 and therefore have avoided the financial panic? Given the rise in house price to income ratios it’s not clear to me how the financial panic could have been avoided at all by monetary policy. However your point on monetary policy and the recession is, as ever, extremely well made.

LikeLike

Mr. Glasner, the base money growth pattern you describe has been seen before:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=sIy

LikeLike

Superb blogging…and again evidence that FOMC meetings should be open and televised…the peevish fixation on inflation is not captured in sanitized minutes released three weeks after the fact…but hearing the word “inflation” literally hundreds of times per FOMC meeting would clue markets as to what the Fed was really going to do…

LikeLike

David,

If tight money caused the October panic, you would have expected to see downgrades of AAA-rated securities occurring after the panic. Remember, these securities ratings assume that they will hold up even in a deep recession. Despite this, there were widespread downgrades during the course of 2008. Clearly, something went inexplicably, and unpredictably wrong with the collateral backing the shadow banking system before the meeting you write about. Clearly, it was not the mild recession we experienced, nor was it “tight money”, as, again, these securities were structured to withstand such events.

LikeLike

David,

Is it necessary that a financial crisis be precipitated by tight money? Can a financial crisis have nothing to do with tight monetary policy? I am thinking in my mind of the 1990s – Mexico, Russia, Argentina, East Asia.

I suppose another obvious question would be – was the postwar era one of financial tranquility because central banks did not pursue tight money? What changed after the 70s?

But I suppose I am asking bigger questions than you intended with this post.

LikeLike

Ilya,

I don’t know much about it, but the UK’s “Secondary Banking Crisis” in the mid-1970s took place at a time of rapid NGDP and base growth. On the other hand, the instability of UK NGDP during the mid-1970s was also very considerable for peacetime.

The US stock market crash in 1987 was a crisis in many ways, but was actually during a mildly inflationary ‘blip’ early in the Great Moderation.

LikeLike

Marcus, Yes, it does. Thanks for the links.

Travis, Obviously, something went very wrong. Whether it was paying interest on reserves, or a failure to articulate a clear strategy for raising spending and prices, or both, or something else is something we will be puzzling over for a long time to come.

Jason, Thanks for the link to your blog. Looks interesting. Forgive me, but I just haven’t had time to read it carefully.

Britmouse, Thanks.

Tom, I don’t say that the Fed could have kept housing prices growing, but the Fed could certainly have kept the prices from falling as much as they did.

The Arthurian, Thanks for the link.

Benjamin, Thanks.

Diego, The economy began deteriorating really badly in the third quarter before the panic. I agree that the financial system was in a fragile condition, but the fragility might not have led to a collapse if the recession had gotten worse fast in the third quarter. There was nothing mild about the decline in real GDP and the rise in unemployment in the third quarter. But I agree with you that there was an exceptional interaction between financial fragility and cyclical and monetary factors that produced the crisis.

Ilya, I guess it depends on what kind of financial crisis that we are talking about. The only one of the cases you mention that I know even a little bit about is the Argentine case. That crisis was produced by a rapid rise in the dollar exchange rate while the Argentine currency was pegged to the dollar, which decimated the Argentine export sector. That was the equivalent of tight money, and the only way for Argentina to escape was to devalue its currency which the government in power had been promising for a decade it would never do under any circumstances. Currency crises can occur when a government tries to maintain a fixed exchange rate and the market no longer believes, for a variety of possible reasons, that the peg will be maintained.

W. Peden, I don’t recall the details of the 1987 crash. People seem to think that it was a fluke inasmuch as it seemed to self-correct, and the market recovered its losses within a year or so.

LikeLike

Hi David.

I do not always agree with your perspective, but your blog is highly thought-provoking.

With regards to a putative inflation-phobia amongst Fed members, in order to prove this, would it not be necessary to demonstrate not just that they were too worried about inflation in July 2008, but that they exhibited a systematic bias in this direction over the course of a few business cycles.

I have myself done this work, as well as lived it since my career as an interest rate speculator began.

It’s actually an exercise I suggest for new hires. Pick a chart of the 2 year T note in your favourite country. Circle the major turning points – highs and lows – and pull up the official minutes, the transcripts (if available) and speeches and comments from central banking officials at the times of these major highs and lows.

The general pattern (and it is pretty consistent) is that policymakers are always ‘wrong’ (ie biased in the direction of the previous trend, and implicitly extrapolating recent developments at that point, and not anticipating the shifts in basic economic conditions that subsequently lead to a change in direction. I am implicitly asking you to trust me here that when the market changes direction it is associated with a run of data releases that support the change in direction. However, I am pretty sure that you will arrive at the same result if you look more directly at shifts in the trend of data representing economic activity itself and study the evolution of the rhetoric around these turning points.

One has the same experience talking to policymakers directly as one lives through major turning points.

Remember summer 2003 when there were all these worries about deflation? A certain former Fed official very close to Greenspan and who retained very good contacts at the Fed after he moved to his consulting business came by and saw us in London. He is a very nice man, and very bright. However, instead of explaining why CPI was artificially depressed due to used cars (0% financing for new cars) and owner’s equivalent rent (utilities are packaged with housing, and energy went up whilst rents did not), his focus was on exactly how the Fed might buy bonds, and the particular operational challenges of doing so. All terribly interesting, but of not practical investment utility because the deflation scare was based upon spurious considerations.

So there is one counterexample for you. The Fed were too worried about inflation in July 2008, and too worried about deflation in July 2003.

The point is that policymakers and conventional economists simply do not have a good record of anticipating economic shifts, as these economic shifts are never seen first in hard data whilst no respectable economist is able to avoid looking primarily at the hard data even though he may know in his heart of hearts that it doesn’t anticipate the future at the very time you most need to be able to do so.

I believe that my points stand on their own, but for what it is worth I did anticipate a deflation bust in July to early August 2008 as commodities and breakeven inflation (the market’s implied anticipation of future inflation) topped, and also the bottom in early Jan 2009 as they bottomed. I may post a link to pieces written at that time in case it may be of interest,

So either I am talking nonsense about the central banks being consistently wrong when things shift (I am not, and you can do the work yourself in a few hours), or you are obliged to go further in demonstrating that not only are they always wrong at turns, but they are especially wrong at disinflationary turns.

(I note that the ECB is perhaps worse than the Fed in this respect. Because of the rather Buba-inspired doctrine of ‘steady hand’ in setting monetary policy, the ECB doesn’t like to change direction in a hurry even when the picture is clearly – to someone who thinks in the way I do – shifting against the old trend. So for example in July 2008, the last ECB hike was exactly the opposite of what was required, and similarly in July 2012).

One question I have for you that is less about logic, and more about one’s approach to being open to modifying one’s thought process in the light of surprises. Suppose that inflation turns out to be substantially higher over the next 3-5 years in the face of policy that is not substantially more accommodative than at present. (Such an outturn likely being signalled rather sooner than 3-5 years by a large rally in breakeven inflation rates).

Would that make you open to reconsidering your perspective and the mode of thought behind it? If so, would you mind if I set a note in my calendar for 18 months time so we can revisit this discussion?

I happen to have a different view to you, and I have set it out in the piece I emailed. This view is based upon the idea that one loses a great deal by doing only analysis and paying inordinate attention to hard data susceptible to models rather than softer, more inchoate impressions about which one may nonetheless think in a systematic fashion.

“its pathological nature at those meetings does have a certain breathtaking quality; it had already been operating for a long time before that. If you look at the St. Louis Fed’s statistics on the monetary base, you will find that the previous recession in 2001 had been preceded in 2000 by a drop of 3.6% in the monetary base.”

3.6% sure doesn’t seem like much given that the Fed eased aggressively in quantitative terms in 1999 to be sure nothing would go wrong over Y2K. given the extent to which they eased, was it really so wrong to take a little bit back? bear in mind the insane equity environment at the time (I do think the Y2K ease in 1999 was responsible for that last leg up that damaged so many reputations of those who had the right view but were just a bit early).

“The housing bubble burst in 2006, but the Fed was evidently determined to squeeze inflation out of the system, as if trying to atone for its sins in allowing the housing bubble in the first place.”

well, it is an open question as to whether the bubble was in housing or credit. I believe it was the latter, and that that is where the real excesses were. my explanation – of a global credit bubble originally triggered by a desperate search for yield at the 2003 low in yields, but one that eventually took on a life of its own – is much more parsimonious as it explains the insanity distributed around the world. you have to have lots of stories that are not obviously linked – one for US and Irish housing, another for Dubai infrastructure, another for industrial-commodity linked plays, another for European peripheral credit.

bear in mind that in this context, although US housing showed clear signs of weakness already in 2006 (and I asked Kohn about it at lunch just after he had been made vice-chair and he wasn’t worried about housing, or the impact of resets – and to be honest nobody else at lunch was worried either), credit spreads continued to compress into February 2007. and since the excesses were clearly in credit (I trust you will grant that at least they were clearly, also, in credit) and the overwhelming consensus economic view (I couldn’t find a soul on my side back then) was that we had rare synchronized global growth, it wasn’t unreasonable within the way the Fed thinks about the world to keep tightening.

“If the Fed had moderated its stance in 2008 in response to ample evidence that the economy was slowing, there is good reason to think that the economy would not have contracted as rapidly as it did, starting, even before the Lehman collapse, in the third quarter of 2008, when, we now know, the economy had already begun one of the sharpest contractions of the entire post World War II era”.

it would have been better if they had eased more quickly. however 1) do you believe there was a credit bubble? 2) can you find any instance of a credit bubble bursting that was not horrible, to a greater or lesser extent?

bear in mind also that the Fed has institutional memory of making the opposite kind of mistake. The Fed loosened in response to the 87 crash (which if you study the sectoral capacity utilisation data turned out to be associated with a shift in the pattern of economic activity, although not a collapse)i, and arguably that made the subsequent S&L bust worse when the silly boom did finally reach its natural conclusion.

“A financial panic is an acute breakdown of the financial system, always associated with a period of monetary stringency when demands for liquidity cannot be satisfied owing to a contagious loss of confidence in the solvency of borrowers and lenders. The crisis is typically precipitated by a too aggressive tightening of monetary conditions by the monetary authority seeking to rein in inflationary pressures.”

Like the panics of 1907, 1914, 1873, the Overend and Guerney episode and the C19 Barings crisis? Would we not be better off returning to the doctrine of Mills and recognize that a panic is a mass psychological phenomenon relating to a loss of confidence in credit that we still do not fully understand and are unable to predict and that may have multiple triggers, and monetary policy tightening may serve as one of these?

Is there any real evidence to suggest that over-tightening monetary policy has a particular tendency to induce panics, and that the great preponderance of panics have been induced by too-tight policy? Bear in mind that pre central banking it is hard to untangle cause from effect, since a loss of confidence would be reflected in a loss of specie and tendency to force the central bank to tighten to protect its reserve. And on the other hand, post central banking a panic arriving some way into the boom from causes that are putatively of non-monetary policy origin will ex post facto make it appear that obviously policy was too tight, when it simply wasn’t realistically clear to anyone at the time not successfully peering into the misty future.

Shall we put it another way? Of people writing in the period say June 2006-July 2008, which serious people were warning of a credit bust and nasty downturn in the economy. And which of these were right for the right reason, and have had a consistently good track-record rather than being permanently bearish? A stopped clock will be right twice a day.

I know of two: Marc Faber, and Jim Rogers. Marc has the perception of being permanently bearish, but if one reads his serious work rather than just listening to how he is forced to simplify it on TV, one may see that he wrote in summer 2003 a piece on reflation. Fred Sheehan, Kurt Richebacher and Doug Noland were ultimately right for a while, but one must recognize too that they started sounding the warning alarms rather too early! (This may be unfair to Sheehan as I don’t recall so clearly now).

And for what it is worth, personally I did speak to the IMF Financial Stability chap in early 2005 at the request of the Bank of England. Quaintly, they were worried about the USD/JPY carry trade by hedge funds (always fighting the last war, these policy-makers). I told him not to worry about the hedge funds, but about the banks, and what they were buying. I wasn’t the only practitioner to see things developing nastily, but there was a very limited audience for this kind of view, and it was perceived as extreme and investors are put off by this kind of thing.

One should also credit Crispin Odey, who put out (rather early) a very good study on the emerging credit bubble by a serious student of bubbles (whose name temporarily escapes me).

Don’t you see it as a problem to explain after the fact what the Fed should have done after the fact bearing in mind one had the opportunity to say so at the time, and for whatever reason chose not to say so? Wouldn’t it be more in keeping with the scientific spirit to make pattern predictions?

– the Fed is currently doing X. I believe X’ would be more appropriate, and really, Y is the proper policy

– if it continues to do X, as I believe likely, then this is the shape of events that I believe is likely.

I shall throw a hostage to fortune and suggest the following

a. central banks have maintained very easy policy for too long in the belief that the labour market (and maintaining nominal GDP growth) is what is key and in the belief that inflation is the least of their worries following a financial crisis and that should it begin to appear this is a problem that they know well how to solve and that they will at that point act promptly to raise rates and that this will eliminate any prospect of serious inflation taking hold (bearing in mind that it would be desirable to risk somewhat higher median inflation to truncate the disastrous tail of deflation)

b. forward guidance (as adopted most clearly by the bank of england) makes sense if the central bank has superior insight to the market. however central banks (and the Old Lady is no exception) have a horrible track record in economic forecasting, whereas historically market movements in yields anticipate shifts in economic activity much better than any forecasting model not itself incorporating such shifts. since the central bank is only able to react with a lag, and in fact has committed itself to act late, this is a recipe for instability.

c. as the work of Samuel Reynard at the SNB demonstrates, it simply is not the case that post financial crisis the link between money/credit and inflation breaks down. what happens is that so long as risk appetite is depressed it does, but risk appetite can shift quickly. when that happens, a great deal of inflation is baked in the cake and it is simply too late to get to price stability without an unacceptable loss of output, whatever comforting stories central bankers tell themselves in order to be able to sleep at night.

d. the labour market has been horrible. it has lately been perking up, and is likely to do so dramatically on a 2-3 year horizon.

e. when this happens there is going to be payback time for the period of subdued wage growth that followed 2000. offshoring and automation as net job destroying processes may turn out to be yesterday’s story. furthermore rising rates will tend to make it less attractive at the margin to replace labour by capital (noting also that a one-shot adjustment lower in rates leads to a stock adjustment spread out in time, meaning that one is in for a surprise if one extrapolates the spurt of adjustment forward indefinitely into the future).

f. inflation is going a lot higher over the next 3-5 years (and we should see breakeven inflation rise markedly, even on an 18 month horizon).

I do hope the tone of my comment is not unduly combative. I believe this is the critical question of the moment, and would love to hear how I am mistaken.

LikeLike

Breakeven inflation – abstracting from technical considerations – is the difference between the nominal yield and the TIPS yield and reflects the market’s implied view of inflation expectations.

Here is a picture of 10 year breakeven rates in relation to Fed transcripts that may help put things into context. (You can see the text more clearly if you zoom in with your browser):

The Fed was extremely concerned in June 2003 about what they perceived as the dangerously low level of inflation, for what turned out to be spurious reasons. One cannot attribute the turnaround to their aggressive actions since although they came close, they never actually then pulled the trigger on bond-buying. Had they actually bought bonds this must surely be seen as likely to have exacerbated the subsequent credit bubble.

I suggested that if one claims to have the right to critique Fed policy, one ought to be able to do so in real time and to be able to say what the implications of policy mistakes would be in a forward-looking manner. (It’s much easier to retrospectively diagnose past policy mistakes, because one knows how it turned out). In other words a prerequisite is that one has demonstrated real-time insight over past episodes when things shifted.

It’s in that spirit that I offer the material below, which may provide some support for my stance.

Note that as a practitioner, my emphasis is much more on what the investment implications of policy will be rather than writing in the spirit of giving advice to policymakers. However I trust the relevance will come across.

I need not say that this is offered in the spirit of contributing to the economic dialogue, and is not intended to be marketing of any sort.

——

Here is the piece I wrote on 8th August 2008 suggesting that the market emphasis on Fed rhetoric was missing the point because the Fed would shortly have other more pressing things to worry about:

“The attention paid to parsing the rhetoric of central banks is out of balance in relation to that paid to trying to figure out the likely ‘fundamentals’ policy makers will be reacting to in a few months time. At turning points in market rates, the public statements of central bankers show that they have less insight into what they will be doing a few months hence than what technical measures of the market imply.

– The supposed ‘US subprime’ crisis has a broader scope than initially perceived, and the market is awakening to this possibility. Just as in 2000-2003 Europe and the rest of the world will not be immune.

– There is extreme danger for long positions in cyclical stocks, materials, steels and agriculture.

– US domestic credit growth is slowing – the US consumer has less inclination or ability to borrow, and this is now showing up in the numbers.

– The counterpart of US consumer dissaving is the current account deficit. Ex-oil this is already at levels comparable with the last recession. As energy prices come down and lagged effects of prior hikes are felt in demand destruction, the overall current account should start to improve. The counterpart of the deficit is reserve growth at foreign central banks, and the counterpart of that is domestic liquidity creation suggesting that growth in the rest of the world should start to slow. This is bullish for the dollar. ”

Click to access Kal_Comment_2008_Aug_08.pdf

—-

Here is the piece I wrote on 3rd January 2009 suggesting that breakeven inflation was bottoming. (Since this was a blog post, the rationale was not expressed in terms that may be familiar to an economist, but I can assure you that there was sound economic logic behind it):

Click to access Kal_Comment_2009_Jan_03.pdf

—

Here is the piece I wrote on 30th May 2011 suggesting that prevalent concern over inflation in Europe (encouraged by the ECB) was missing the point that growth was slowing, and that inflation – both breakeven and headline would come down soon enough (which it did):

“Focus on slowing growth ahead, not lagging inflation

– Inflation outlook: short term peak; secular uptrend. Rise in implied breakevens reflects commodity market rally – positioning and sentiment very extended. Just a stabilization in commodity prices will be enough to bring down headline inflation via base effects, and in fact we could see very significant declines in industrial commodity prices.

– Forward-looking indicators: Belgian business confidence a useful barometer and shows deterioration in outlook consistent with US data and other forward-looking Eurozone indicators. ZEW expectations suggest focus on lagging German exports is misplaced and we have a sharp slowdown ahead.

– ECB Policy: hawkish rhetoric leads many to focus on possibility of ECB hiking more aggressively than forwards, but historically ECB open-mouth policy has often been a very bad guide to their actual decisions. Some similarities to July 2008. Should rates be at zero?

– Flight to quality risks: rate hikes in EONIA curve can get pushed out, but possibility of Greek default leading to financial market disruption in Spain and Italy could lead to market pricing an EMU breakup, with German short-end becoming the ultimate safe

haven.

– Relative Valuation: leading indicators suggest growth is slowing much more quickly in Europe than in the US, and given worse sentiment for Europe this should favour Bunds over UST

”

Please do let me know if you think the relevance for the current discussion is not clear.

LikeLike