Larry Summers has a really interesting piece in today’s Financial Times (“Look beyond interest rates to get out of the gloom”), advocating that safe-haven governments (like the US, Germany and the UK) which are now able to borrow at close to zero rates of interest, which adjusted for expected inflation, amount to negative rates. Given such low borrowing costs, Summers argues, governments should be borrowing like crazy to finance any investment that promises even a marginally positive real return, even apart from Keynesian stimulative effects. This is not a new idea, countercyclical public works spending has often been advocated even by orthodox anti-Keynesians as nothing more than sensible budgetary policy, borrowing when the cost of borrowing is cheap and hiring factors of production in excess supply at discounted prices, to finance long-term investment projects. If there is a Keynesian effect on top of that, so much the better, but the rationale for doing so doesn’t depend on the existence of a positive multiplier effect.

But Summers’s argument takes this argument a step further, because as he presents it, the case for doing so is almost akin to engaging in an arbitrage transaction.

As my fellow Harvard economist Martin Feldstein has pointed out, this principle applies to accelerating replacement cycles for military supplies. Similarly, government decisions to issue debt and then buy space that is currently being leased will improve the government’s financial position. That is, as long as the interest rate on debt is less than the ratio of rents to building values, a condition almost certain to be met in a world of government borrowing rates of less than 2 per cent.

These examples are the place to begin because they involve what is in effect an arbitrage, whereby the government uses its credit to deliver essentially the same bundle of services at a lower cost. It would be amazing if there were not many public investment projects with certain equivalent real returns well above zero. Consider a $1 project that yielded even a permanent 4 cents a year in real terms increment to GDP by expanding the economy’s capacity or its ability to innovate. Depending on where it was undertaken, this project would yield at least 1 cent a year in government revenue. At any real interest rate below 1 per cent, the project pays for itself even before taking into account any Keynesian effects.

Now one blogger (Tea With FT) commenting on Summers’s piece found grounds to quibble about whether the rates governments pay on their debt are “free market rates,” because banking regulations allow banks to reduce their capital requirements by holding government debt but must increase their capital requirements as they increase their holdings of private debt.

Lawrence Summers is just another economist fooled by looking only at the nominal low interest rates for government debt of some “infallible” sovereigns, “Look beyond the interest rates to get out of the gloom“. Those interest rates do not reflect real free market rates, but the rates after the subsidies given to much government borrowing implicit in requiring the banks to have much less capital for that than for other type of lending.

If the capital requirements for banks when lending to a small business or an entrepreneurs was the same as when lending to the government… then we could talk about market rates. As is, to the cost of government debt, we need to add all the opportunity cost of all bank lending that does not occur because of the subsidy… and those could be immense.

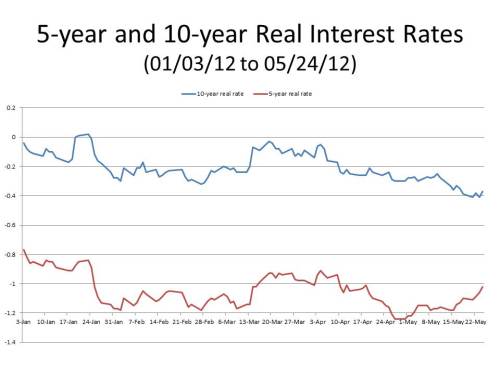

I’m not going to get in that discussion here, but the point seems well-taken. But leaving that aside, I want to ask the following question: As long as the interest rate on TIPS is negative, why is the US government not selling massive amount of TIPS, using the proceeds to retire conventional Treasuries while earning a profit on each exchange of a TIPS for a Treasury? That would be true arbitrage whatever the merits of Tea With FT’s argument. Are there statutory limits on the amount of TIPS that can be sold?

The issue also seems to bear on the discussion that Steve Williamson and Miles Kimball have been having (here, here, and here, and also see Noah Smith’s take) about whether the Modigliani-Miller theorem applies to the Fed’s balance sheet. If there are arbitrage profits available exchanging conventional Treasuries for TIPS, what does that say about whether the Modigliani-Miller theorem holds for the Fed?

My next question is: if there are arbitrage profits to be made from such an exchange of assets, what is the mechanism by which the arbitrage profits would be eliminated? Why would exchanging Treasuries for TIPS alter real interest rates or inflation expectations in such a way as to eliminate the discrepancy in yields? Maybe there is something obvious going on that I’m not getting. What is it? And if the reason is not obvious, I’ld like to know it, too.

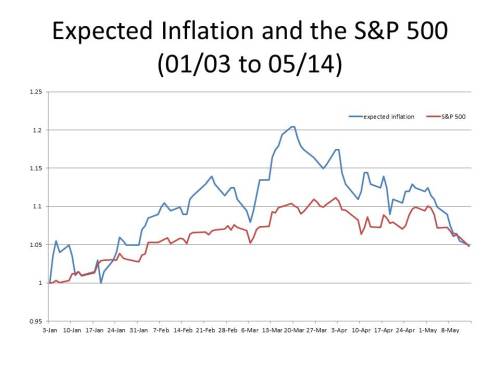

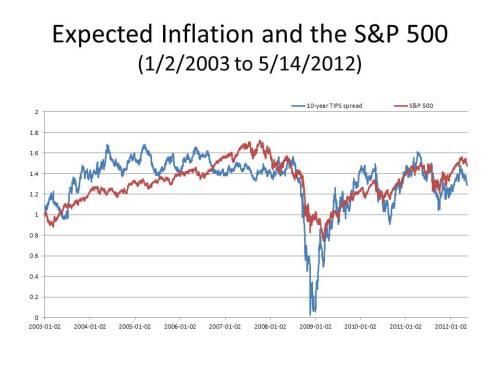

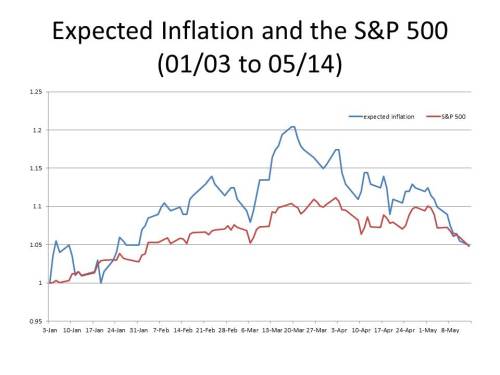

UPDATE: Thanks to Cantillonblog and Foosion for explaining the obvious to me. In my haste, I wasn’t thinking clearly. Given the expectation of inflation, the negative yield on TIPS will have to be supplemented by a further payment to compensate for the loss of principle due to inflation, so the cash flows associated with either a conventional Treasury or a TIPS are equal if inflation matches the implicit expectation of inflation corresponding to the TIPS spread. But suppose the Treasury did issue more TIPS relative to conventional Treasuries, wouldn’t the additional Treasuries be sold to people who had slightly higher expectations of inflation than those who were already holding them? Or alternatively, wouldn’t the very fact that the government was trying to sell more TIPS and fewer conventional Treasuries cause the public to revise their expectations of inflation upwards? That’s not exactly the conventional channel by which either monetary policy or fiscal policy affects inflation expectations, but it does suggest that the policy authorities have some traction in trying to affect inflation expectations. In addition, since interest rates fell close to zero after the financial panic of 2008, inflation expectations have responded in the expected direction to changes in the stance of monetary policy, rising after the announcment of QE1 and QE2 and falling when they were terminated.

UPDATE 2: I am posting too fast today. If the Treasury increased the quantity of TIPS being offered, it would drive down the price of the TIPS, increasing the real inflation adjusted yield. An increased real yield, at a given nominal rate, would imply a reduced break even TIPS spread, or reduced inflation expectations. Thus, increasing the proportion of TIPS relative to conventional Treasuries would induce savers with relatively lower inflation expectations than those previously holding them to begin holding them as well. Alternatively, increasing the proportion of TIPS outstanding would encourage individuals to revise their expectations of inflation downward because the Treasury would be increasing its exposure to inflation. But the point about the applicability of the MM theorem still applies with the appropriate adjustments. At least until further notice.

.

.