The following (with some minor revisions) is a Twitter thread I posted yesterday. Unfortunately, because it was my first attempt at threading the thread wound up being split into three sub-threads and rather than try to reconnect them all, I will just post the complete thread here as a blogpost.

1. Here’s an outline of an unwritten paper developing some ideas from my paper “Hayek Hicks Radner and Four Equilibrium Concepts” (see here for an earlier ungated version) and some from previous blog posts, in particular Phillips Curve Musings.

2. Standard supply-demand analysis is a form of partial-equilibrium (PE) analysis, which means that it is contingent on a ceteris paribus (CP) assumption, an assumption largely incompatible with realistic dynamic macroeconomic analysis.

3. Macroeconomic analysis is necessarily situated a in general-equilibrium (GE) context that precludes any CP assumption, because there are no variables that are held constant in GE analysis.

4. In the General Theory, Keynes criticized the argument based on supply-demand analysis that cutting nominal wages would cure unemployment. Instead, despite his Marshallian training (upbringing) in PE analysis, Keynes argued that PE (AKA supply-demand) analysis is unsuited for understanding the problem of aggregate (involuntary) unemployment.

5. The comparative-statics method described by Samuelson in the Foundations of Econ Analysis formalized PE analysis under the maintained assumption that a unique GE obtains and deriving a “meaningful theorem” from the 1st- and 2nd-order conditions for a local optimum.

6. PE analysis, as formalized by Samuelson, is conditioned on the assumption that GE obtains. It is focused on the effect of changing a single parameter in a single market small enough for the effects on other markets of the parameter change to be made negligible.

7. Thus, PE analysis, the essence of micro-economics is predicated on the macrofoundation that all, but one, markets are in equilibrium.

8. Samuelson’s meaningful theorems were a misnomer reflecting mid-20th-century operationalism. They can now be understood as empirically refutable propositions implied by theorems augmented with a CP assumption that interactions b/w markets are small enough to be neglected.

9. If a PE model is appropriately specified, and if the market under consideration is small or only minimally related to other markets, then differences between predictions and observations will be statistically insignificant.

10. So PE analysis uses comparative-statics to compare two alternative general equilibria that differ only in respect of a small parameter change.

11. The difference allows an inference about the causal effect of a small change in that parameter, but says nothing about how an economy would actually adjust to a parameter change.

12. PE analysis is conditioned on the CP assumption that the analyzed market and the parameter change are small enough to allow any interaction between the parameter change and markets other than the market under consideration to be disregarded.

13. However, the process whereby one equilibrium transitions to another is left undetermined; the difference between the two equilibria with and without the parameter change is computed but no account of an adjustment process leading from one equilibrium to the other is provided.

14. Hence, the term “comparative statics.”

15. The only suggestion of an adjustment process is an assumption that the price-adjustment in any market is an increasing function of excess demand in the market.

16. In his seminal account of GE, Walras posited the device of an auctioneer who announces prices–one for each market–computes desired purchases and sales at those prices, and sets, under an adjustment algorithm, new prices at which desired purchases and sales are recomputed.

17. The process continues until a set of equilibrium prices is found at which excess demands in all markets are zero. In Walras’s heuristic account of what he called the tatonnement process, trading is allowed only after the equilibrium price vector is found by the auctioneer.

18. Walras and his successors assumed, but did not prove, that, if an equilibrium price vector exists, the tatonnement process would eventually, through trial and error, converge on that price vector.

19. However, contributions by Sonnenschein, Mantel and Debreu (hereinafter referred to as the SMD Theorem) show that no price-adjustment rule necessarily converges on a unique equilibrium price vector even if one exists.

20. The possibility that there are multiple equilibria with distinct equilibrium price vectors may or may not be worth explicit attention, but for purposes of this discussion, I confine myself to the case in which a unique equilibrium exists.

21. The SMD Theorem underscores the lack of any explanatory account of a mechanism whereby changes in market prices, responding to excess demands or supplies, guide a decentralized system of competitive markets toward an equilibrium state, even if a unique equilibrium exists.

22. The Walrasian tatonnement process has been replaced by the Arrow-Debreu-McKenzie (ADM) model in an economy of infinite duration consisting of an infinite number of generations of agents with given resources and technology.

23. The equilibrium of the model involves all agents populating the economy over all time periods meeting before trading starts, and, based on initial endowments and common knowledge, making plans given an announced equilibrium price vector for all time in all markets.

24. Uncertainty is accommodated by the mechanism of contingent trading in alternative states of the world. Given assumptions about technology and preferences, the ADM equilibrium determines the set prices for all contingent states of the world in all time periods.

25. Given equilibrium prices, all agents enter into optimal transactions in advance, conditioned on those prices. Time unfolds according to the equilibrium set of plans and associated transactions agreed upon at the outset and executed without fail over the course of time.

26. At the ADM equilibrium price vector all agents can execute their chosen optimal transactions at those prices in all markets (certain or contingent) in all time periods. In other words, at that price vector, excess demands in all markets with positive prices are zero.

27. The ADM model makes no pretense of identifying a process that discovers the equilibrium price vector. All that can be said about that price vector is that if it exists and trading occurs at equilibrium prices, then excess demands will be zero if prices are positive.

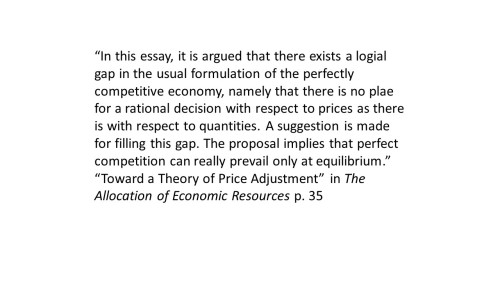

28. Arrow himself drew attention to the gap in the ADM model, writing in 1959:

29. In addition to the explanatory gap identified by Arrow, another shortcoming of the ADM model was discussed by Radner: the dependence of the ADM model on a complete set of forward and state-contingent markets at time zero when equilibrium prices are determined.

30. Not only is the complete-market assumption a backdoor reintroduction of perfect foresight, it excludes many features of the greatest interest in modern market economies: the existence of money, stock markets, and money-crating commercial banks.

31. Radner showed that for full equilibrium to obtain, not only must excess demands in current markets be zero, but whenever current markets and current prices for future delivery are missing, agents must correctly expect those future prices.

32. But there is no plausible account of an equilibrating mechanism whereby price expectations become consistent with GE. Although PE analysis suggests that price adjustments do clear markets, no analogous analysis explains how future price expectations are equilibrated.

33. But if both price expectations and actual prices must be equilibrated for GE to obtain, the notion that “market-clearing” price adjustments are sufficient to achieve macroeconomic “equilibrium” is untenable.

34. Nevertheless, the idea that individual price expectations are rational (correct), so that, except for random shocks, continuous equilibrium is maintained, became the bedrock for New Classical macroeconomics and its New Keynesian and real-business cycle offshoots.

35. Macroeconomic theory has become a theory of dynamic intertemporal optimization subject to stochastic disturbances and market frictions that prevent or delay optimal adjustment to the disturbances, potentially allowing scope for countercyclical monetary or fiscal policies.

I think I agree with this post. It is fascinating.

I have a thought, sparked by the idea of “equilibrium.”

Let us suppose at any point global capital markets are held to be in “equilibrium.” That is, investors have made their choices between consumption and investment.

So, then a central bank adds $5 trillion to the pool of global capital, by buying $5 trillion in securities. This has an initial effect of, ceteris paribus, lowering rates.

Okay, so some investors slope off from capital markets, finding returns too low, and prefer to consume. In other words, global capital markets are full, and when a central bank adds $5 trillion to global capital markets, the excess rolls off the top into consumption.

Thus, if one assumes global capital markets in equilibrium, then conventional QE actually may actually primarily boost consumption (in addition to various second order effects, the wealth effect, etc).

LikeLike

In Arrow’s Nobel Memorial Speech (p 122) there is a line that reads: “Now the elementary point about this inequality is that xh [h is subscript] , yf [f is subscript] are independent of each other.”

In other words consumption is independent of production. Now the whole point of the General Theory was that production and consumption are not independent and that therefore the Marshallian apparatus of demand and supply was incorrect.

So how is “General Equilibrium” analysis an advance over Marshallian analysis?

LikeLike

Great post, David. Thank you. It reorganizes and condenses in a nice and clear sequence arguments that you have made on previous occasions. This is major critique to GE Analysis. I wonder, in this regard, what is your opinion about Disequilibrium Macroeconomics that was developed in the 1970s (by Barro, Grossman, Malinvaud, Bénassy et al, following Patinkin, Clower and Leijonhufvud), but was then abandoned (probably because of the fascination exercised by RE on young economists). Do you think that kind of analysis should be resurrected? Why is not even heterodox economics (at least to my knowledge) reconsidering and looking into it?

I wish to point your attention to a number of typos in the post: in the citation of Arrow and above all in para 32, where some text must have gone lost and a sentence appears that is then repeated in para 33, and which closes with an incomplete/unclear sentence.

LikeLike

Benjamin, Thanks for your comment. The other alternative is that the additional cash is injected and held willingly so that the interest rate change is negligible.

philipij, I searched for the quote in Arrow’s Nobel Lecture and couldn’t find it. I searched for the quotation you provide and I looked at p. 122. Can you point me to the exact location. This is just a guess, but maybe the independence is at the household level not the aggregate level.

Biagio, Thanks for your close reading. You are right there was a glitch in my attempt to cut and paste from Twitter to my blog. I think that I have fixed the problem. As for your substantive question, I would have no problem with its resurrection, but that’s not the change I’m thinking of, which is to focus on the effect of conflicting price expectations that lead to disappointment and have potentially significant effects as plans have to be revised or scrapped as a result of the disappointment of expectations.

LikeLike

Benjamin, Thanks for your comment. The other alternative is that the additional cash is injected and held willingly so that the interest rate change is negligible.

David— well, if held as paper cash and kept out of circulation, that is stuffed under mattresses, then I think conventional QE would have no effect on interest rates. But if cash is held as digital deposits at banks, then I would think it would lower interest rates (ceteris paribus).

LikeLike

Benjamin, QE works by purchasing assets (Treasuries) in exchange for deposits at the Fed. There may be some effect on interest rates, whatever happens to the Fed deposits, but I don’t think that the effect on interest rates is significant. I discussed this fairly recently in these two posts

LikeLike

The only correct “general” theory is The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. The “general” in Keynes’s book is intended to mean that it is an attempt to explain why aggregate demand changes, why there are product gluts and involuntary unemployment. Previous analyses assumed that aggregate demand was a given.

The fact that The General Theory is right implies that “general equilibrium” in the Walras-Arrow sense is impossible.

When I say that The General Theory is right I mean it in a big picture kind of way. The details are mostly incorrect, including such a fundamental claim as that recessions are set off by a fall in investment.

LikeLike

I was responding only to your quote from Arrow only to say that I wasn’t able to find the quote in the published version of the lecture online. So I wasn’t going beyond the four corners of the quote in your first comment.

Just by coincidence I have been reading been reading a volume of essays entitled Microfoundations Reconsidered, edited by Duarte and Lima. Two of the essays by Hands and by Mirowski directly address the question of the compatibility of Walrasian GE analysis and Keynesian theory. I think that there is a degree of overlap between GE theory (in the broadest sense) and Keynesian theory, but I don’t think the economics profession has yet found a way to explore that overlap in a fruitful way. I think Hicksian temporary equilibrium theory offers the best approach, but Hicks himself failed to pull it off in his IS-LM model, which is a one-period model, when (at a minimum) a two-period model was necessary. I discussed some of these issues in the two post from last July that I linked to in my earlier reply to Benjamin Cole. I don’t think I have any more to say on the subject right now.

LikeLike

The link to the lecture is https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/arrow-lecture.pdf.

LikeLike

David,

“I think that there is a degree of overlap between GE theory (in the broadest sense) and Keynesian theory….”

Could you please explain or expand on this?

Thanks.

LikeLike

Henry, What I meant is that Keynes was rejecting the partial equilibrium analysis of a market — the labor market — that pervades the entire economy so that the ceteris paribus assumption that underlies any partial equilibrium analysis cannot be maintained. Keynes’s response to the failure of partial equilibrium analysis was not to resort to general equilibrium analysis, but to formulate a new kind of aggregate model the income-expenditure model and to define equilibrium in terms of aggregate flows of income and expenditure (or alternatively savings and investment). That led to multiple attempts to translate the Keynesian terminology into general equilibrium analysis. By and large, those attempts have not been terribly successful, partly because of problems in the Keynesian income-expenditure model and partly because of different kinds of problems in the general equilibrium model. We are still struggling to reach some sort, pardon the expression, synthesis. I hope to have more to say about that topic in a future post.

LikeLike

David,

As you know I have argued that GET is entirely unequipped to deal with macroeconomic issues. GET has at its foundation the mechanism of relative prices and allocative efficiency. It assumes independent supply and demand functions. It also assumes full employment of resources and hence must stumble immediately as a theory of macroeconomics. Whereas, on the other hand, Keynesianism focuses on adjustments to spending to shift the macroeconomy from one equilibrium state to another.

Benjamin Cole above raised the example of economic agents making choices about the balance between consumption and investment expenditure. This is entirely a switching expenditure approach and not an approach engendering altering the total level of spending. So it has no macroeconomic consequences.

I would suggest a possible way to a synthesis might be the following.

The basic GET model has two elements, a production possibilities frontier and a budget constraint. The locus of the PPF depicts those bundles of goods that exhibit full employment of resources. The equilibrium point is where the a marginal change in the PPF equates to the relative price ratio establishing the budget constraint.

Consider what happens when there is a retrenchment of resources, that is a recession. Producers make decisions about what level of resource use is appropriate given expectations about changed demand conditions. This effectively shifts the PPF inwards. Consumers of goods make new decisions about current and future purchases based on an expected reduction in income. So the budget constraint shifts inward.

Both the PPF and the BC shift in. A new equilbrium is then struck given the new regime of expectations – expectations not about relative prices but about future levels of income.

A new set of relative prices will be established which determine the allocative settings of the economy, at the new level of income.

The essence is that it is not relative prices or the expectations about relative prices which sets the new macro equilibrium point but expectations about future income.

This is why I would argue that your fascination with Hayek, Hicks and Radner etc. is misdirected.

I am still wondering about how the interdependence of supply and demand at the level of the macroeconomy and the fallacy of composition impinges on the approach I have outlined above.

LikeLike

Henry, Thanks for your comment. As you know, I have considered your arguments and tried to respond to them, so I have little hope that either of us will be persuaded by the other, but it doesn’t hurt to keep trying.

Let me begin first, by asking what you mean by “independent supply and demand functions.” Second, I don’t know what you mean by assuming full employment of resources. The definition of equilibrium is such that resources with positive value are fully employed, but the existence of an equilibrium is proved not assumed. Third, you say that because of the assumption (or proof) of full employment, it cannot serve as a theory of macroeconomics. That argument might be plausible if the theory of general equilibrium could not have any content except for its characterization of an equilibrium state with full employment. I disagree, because it seems to me at least conceivable that the theoretical apparatus of general equilibrium analysis could be modified in such a way as to permit the characterization of states that are not equilibrium states.

As to the rest of your comment, I admit to being confused. I don’t regard a recession as a “retrenchment” of resources. I view it as, among other things, an inconsistency between the plans and expectational assumptions of agents implying that many agents will be disappointed as their developments unfold which are contrary to their expectations requiring the revision or abandonment of plans. Resources, physical and human capital, may become unusable or less valuable than had been anticipated in consequence. Revaluation of resources and alterations in spending patterns that result induce a series of further adjustments, but there is no guarantee that those adjustments will lead to greater coherence among the newly formulated plans than there was among the old plans that turned out to be unfeasible. That is why I think my fascination with Hayek, Hicks, and Radner, (and Hawtrey too!) is not misdirected. And Keynes deserves great credit as well, though he was getting at these taking a much different.

Finally, forgive me, but I can’t figure out what the last sentence in your comment means.

LikeLike

The point that Henry makes about independent supply and demand functions is exactly the assumption in Arrow’s Nobel Prize speech: that production and consumption are independent of each other.

In Keynes these come into equality over time through the variables of income and saving.

In Marshall the assumption is that the supply curve can be drawn sloping upward to the right independent of the demand curve. GE theory makes exactly the same assumption that supply is independent of demand. In reality, when an economy is approaching full employment the supply curves of most products slope upwards to the right. In an economy emerging out of recession the supply curves of most products would slope downwards to the right.

LikeLike

About the independence of supply and demand:

Your post on Jack Schwartz has an interesting quote from Keynes which I partly reproduce below:

“It is the great fault of symbolic pseudomathematical methods of formalizing a system of economic analysis . . . that they expressly assume strict independence between the factors involved and lose all their cogency and authority if this hypothesis is disallowed …”

LikeLike

David,

“…..but it doesn’t hurt to keep trying.”

I appreciate your responding to my comment and being willing to engage in a discussion. I am as much interested in understanding your thoughts on Hicks and Radner as I am in putting forward some alternate ideas.

‘Let me begin first, by asking what you mean by “independent supply and demand functions.” ‘

Take the manufacturer of Lamborghinis. He employs people to build his vehicles. The wages he pays to his workers (a component of his supply function) has no bearing on the demand for the vehicles he manufactures. It is unlikely his employees can afford the vehicles they build. This is an extreme example. If he was manufacturing bicycles, in all probability, his workers could afford to purchase the bicycles they build. However, it is unlikely that his workers would devote a large portion of their wages to purchasing the bicycles they build. The manufacturer has to rely on a wider market. In either case, what the manufacturer pays his employees has little impact on the sales of his output. So at the micro (firm) level, supply and demand curves are independent. GET is essentially a theory about what happens at the individual firm and consumer level. It is a theory about how individual decision makers react to relative prices. It a theory concerned with simultaneous equilibrium in a myriad of individual markets. It is not a theory of macroeconomic equilibrium. Changes in relative prices causes movement along the PPF and not shifts in the PPF.

However, at the macro level, what manufacturers in aggregate pay their employees is directly related to aggregate income. If manufacturers in aggregate increase the wage of their employees they are effectively giving their employees a larger share in the value of aggregate production. In a very real sense, one man’s spending is another man’s income.

And let us recall what a supply and demand function as found in GET is. It is the explication of the relationship between price and output.

At the macro level, there is no such demand and supply curves. There is the relationship between spending, income and output. So to talk about the interdependence of supply and demand at the macro level is, strictly speaking, nonsensical. At the macro level there is spending and output. Aggregate output is not adjusted on the basis of price signals or expected prices but on the basis of expectations about income.

LikeLike

And I would add to my last paragraph that adjustment on the basis of changes in the expectations of income cause shifts in the “effective” PPF (as defined in my original comment).

LikeLike

David,

“I don’t know what you mean by assuming full employment of resources.”

It is an assumption of the standard GET model.

The economy is considered to be operating on the PPF and nowhere else.

Movements along the PPF are effected by changes in relative prices.

Shifts in the “effective” PPF are caused by changes in expectations concerning future income.

LikeLike

David,

“…you say that because of the assumption (or proof) of full employment, it cannot serve as a theory of macroeconomics. ….because it seems to me at least conceivable that the theoretical apparatus of general equilibrium analysis could be modified in such a way as to permit the characterization of states that are not equilibrium states. ”

I can begin to see how invoking Hick’s temporary equilibrium and Radner’s rational expectations might change the equilibrium point, but these are movements along the PPF, as far as I can see. They cannot explain shifts in the PPF to another position, which I call the effective PPF. I would say only changes in income expectations would do that.

LikeLike

David,

“I don’t regard a recession as a “retrenchment” of resources. I view it as, among other things, an inconsistency between the plans and expectational assumptions of agents implying that many agents will be disappointed as their developments unfold which are contrary to their expectations requiring the revision or abandonment of plans”

I accept that expectations and plans change and this alters macroeconomic settings (and by that I mean cause a shift in the effective PPF), if you mean changes in expectations about income. I would not say this about changes in expectations in prices (causes movement along PPF).

And inevitably a recession is a retrenchment of resources. There is less labour and capital employed or they are not employed to their full potential.

LikeLike

David,

“Finally, forgive me, but I can’t figure out what the last sentence in your comment means.”

I am not so sure either. 🙂

GET is a theory about the simultaneous equilibrium in a multitude of individual markets. These markets exhibit supply and demand functions. I have attempted to explain above what I mean by “independence”. I suspect a full explanation would go deeper than the one I have offered. GET is really at the level of the microeconomy.

At the level of the macroeconomy, as I have argued above, it is probably nonsensical to talk about the interdependence of supply and demand functions because supply and demand functions (i.e. the relationships between output and prices) are not the relevant mechanisms involved in adjustment from one macro equilibrium point to another (i.e. shifts in the effective PPF), changes in expectations about future income are.

The fallacy of composition is in part relation to the notion that supply and demand functions are not relevant to the adjustment process (that is, what causes shifts in one equilibrium point to another).

The fallacy of composition is deeper than this. However, I would say that the FoC is not relevant to GET and microeconomics because GET is a theory about the obtaining of equilibrium in individual markets (under strict assumptions). This equilibrium point is a singularity and rests on the ultimate PPF. Whereas Keynesianism is a theory about the infinite possible equilibrium points that might obtain given how expectations about income might change and impact the level of resource usage and how the PPF might shift inwards or back outwards after an inward shift.

LikeLike

Henry Rech,

You said:

‘At the macro level, there is no such demand and supply curves. There is the relationship between spending, income and output. So to talk about the interdependence of supply and demand at the macro level is, strictly speaking, nonsensical. At the macro level there is spending and output. Aggregate output is not adjusted on the basis of price signals or expected prices but on the basis of expectations about income.’

Did you mean “independence of supply and demand at the macro level” ?

LikeLike

philipji,

I did say several things in that paragraph that seem strange – further clarification of I what I was trying to say is required.

Why is macroeconomics of interest?

I would say it is of interest because it is the collection of notions which endeavours to explain why economies exhibit mass scale retrenchment of output and employment and also endeavours to explain inflation.

Macroeconomics is also interested in formulating policy actions which mitigate unwanted developments in output/employment retrenchment and inflation.

David argues that the path to the latter is through understanding how changes in price expectations, which change plans, impacts on the macroeconomy (that is, the general level of output). I do not see how this is a viable approach within the sphere of general equilibrium theory as it is currently formulated. David has said his own approach to this question is coming – I am looking forward to see what he has to say.

I discount this approach because GET is a theory that assumes that the economy is working on the PPF and no where else. It assumes a given level of resource usage compatible with the PPF. It is really a theory about allocative efficiency, relying on the mechanism of relative prices. This is about expenditure SWITCHING.

Whereas the macroeconomic problem is one of taking the economy from one level of output and one level of resource usage to an entirely different level. I argue that this is only possible by changing the LEVEL of spending. As I understand this, this was Keynes’ approach. The macroeconomic problem is really fairly straight forward – if you don’t like the level at which the economy is functioning, change the level of spending in the direction required.

Now GET has at its analytical basis demand and supply functions (there are precursor indifference functions and production functions but we needn’t go there). They depict the relationship between price and output. They assume a given level of income and resource availability. Individual functions are aggregated into market functions. Equilibrium price discovery is sought in these individual markets. GET is about the simultaneous attainment of equilibrium (that is, the equality of output demand and output supply) in all markets.

I have argued above that these demand and supply functions are independent. Now demand functions in one market are interdependent with demand functions in other markets. This is functionalized in the budget constraint. With a given income, if a consumer buys more of one thing he has to buy less of another. Supply functions in different markets are also interdependent. This finds expression in the PPF which depicts the trade off between use of multiple resources.

At the level of macroeconomic adjustment, what is relevant is changes in income expectations. Changes in income expectations shifts these functions about. When these expectations change, the level of resource usage at which the economy is operating shifts. At that new level of resource usage and income expectations new relative prices are formed and a new set of equilibrium conditions is attained.

So what changes the general level of output is not changes in relative prices – i.e. movements along the demand/supply functions – but shifts in these functions. In that sense, demand and supply functions operate differently than they do as mechanisms for resource allocation. In that sense they are not relevant to macroeconomic adjustment. At the level of macroeconomic adjustment, changes in income expectations changes the level of spending. At the level of macroeconomic adjustment, the relationship that matters is not that between prices and output but that between spending and output.

So in saying that the interdependence of supply and demand functions at the level of the macroeconomy is nonsensical I was alluding to the considerations immediately above.

However, having said that, there still is the notion, at the level of the macroeconomy, that one man’s expenditure is another man’s income – which suggests supply and demand functions are interdependent. However, I admit I have some difficulty in reconciling this idea with the idea that interdependence is not relevant at the level of the macroeconomy.

Perhaps the way to reconcile this is to say that demand and supply functions reflect expected income and planned expenditure and are thus ex ante behavioural relationships. Whereas to say one man’s expenditure is another man’s income is an ex post relationship – a non-behavioural accounting relationship.

LikeLike

Henry Rech,

I agree with you about many things. But I think the point in Keynes is that demand and supply are not independent, as they are in Marshall and as is assumed by GET as the quote from Arrow’s Nobel speech shows, although this becomes most obvious at an aggregate level.

LikeLike

philipji,

I used to believe that, at the macro level, supply and demand functions were interdependent, a la Keynes. And I do have difficulty letting go of this idea.

Perhaps, again, the way to think of this is functionally/behaviourally. Consider a consumer making a purchase or producer making production plans. The consumer considers his expected income, the price of the good and hence his ability to purchase other goods, his need to balance his cashflow needs which takes into account his level of debt repayments. Ditto the producer. He is interested in his profitability and his need to balance his cashflow needs. Neither of them, in making their decisions, consider the fact that their expenditure impacts the income of another. This does not feature in their decision making. In that sense, their demand and supply functions cannot be interdependent. But we can say, after the fact, that their expenditures are the other’s income as a matter of pure macro accounting record.

LikeLike

I am not entirely satisfied with my comment immediately above.

The critical consideration is that consumer/producer behaviour is driven by expectations about future income. In the context of the multiplier process, as one spends, the other’s income is incremented, changing the other’s actual income, impacting the other’s decision making.

I’ll have to reread what Keynes wrote on the matter.

LikeLike

I have reconsidered my ill considered excursion off into the wilderness on interdependence and have returned to my original belief. To the extent that demand and supply functions are a function of income, they are interdependent.

LikeLike

//To the extent that demand and supply functions are a function of income, they are interdependent.//

I agree.

LikeLike

Henry and phillpji, First GET is more than a theory of individual households trying to “maximize their utility” and firms trying to maximize profit. That is one part of GET; the other part is how the interdependent plans of independent decision makers can be reconciled so as to be mutually consistent and simultaneously executed. In that sense, it is true that individual supply and demand curves are not independent and GET fully recognizes that. GET is therefore a theory coordination not just a theory of optimization.

GET also fully recognizes that household demands depend on income and that the amount that firms must plan to supply depends on their forecast of demand which in turn depends on the income of their customers. All of that is implicit in the coordination of individual plans that is realized when an equilibrium price vector forms the basis of individual plans to consume and produce.

Finally, the full-employment equilibrium is not assumed it is shown to follow from the assumptions of the model. The assumptions are pretty stringent and unlikely to be satisfied in the real world, but model provides a benchmark and makes it possible to theorize about the causes of a failure to achieve or to operate in the neighborhood of an equilibrium.

It is Marshallian partial equilibrium that specifically assumes independence of demand and supply and focuses attention on a single market and analyzes the supply and demand curves for a single market under the assumption that income and all prices but the market under consideration are either held constant or are irrelevant to price determination in the specific market being analyzed.

That is why Marshall assumed that the marginal utility of income is held constant when drawing a demand curve and why at Chicago from about 1940 till Friedman left in 1976, the Hicks/Slutsky equation was regarded with a combination of horror and contempt because it broke down the response of consumer demand to a price change into a substitution effect and an income effect. The income effect was regarded as a heretical violation of the Marshallian precept that the demand curve holds all prices and incomes constant.

The difference of course is that Hicks and Allen were defining a Walrasian demand curve suitable for GET and Chicagoans were defining a Marshallian demand curve for partial equilibrium analysis.

LikeLike

David,

“GET also fully recognizes that household demands depend on income and that the amount that firms must plan to supply depends on their forecast of demand which in turn depends on the income of their customers. ”

The “standard” model of GET that I was taught assumes income is given and fixed. And if it is not then the optimization algorithm is robbed of its basic element.

In my version of synthesis, income (or at least expectations of income) changes. This shifts the PPF and the BC. When examining macroeconomic behaviour I would say this has to happen first. Then a new optimization begins and new relative prices established (microeconomic behaviour). Microfoundations cannot describe macro effects and behaviour.

“Finally, the full-employment equilibrium is not assumed it is shown to follow from the assumptions of the model. ”

In the standard GET, the economy is assumed to operate on the PPF otherwise optimization cannot make sense.

Any diversions from this and the economy is functioning in a Keynesian world. I know you don’t sanction the use of this terminology but that is what it is. GET can only make sense under the assumptions it’s founded on. Anything else and it’s no longer GET.

Hicks/Slutsky is really irrelevant to this discussion. H/S is merely a way of formalizing the characterization of different types of goods into normal, inferior and Giffen goods. It is merely about describing how the price effect changes quantity demanded as price changes. It breaks the price effect into a substitution effect and an income effect (as relative price changes the effective income of the consumer changes). It has nothing to say about the effect of changes in income on demand. Pure GET does not allow for changes in income.

It was Keynes that formalized the understanding of the effect of changes in income on macro equilibrium.

LikeLike

David,

Did you check out the reference I pointed in Arrow’s Nobel Prize speech to production being independent of consumption?

It means that firms produce in the belief that everything they produce can be sold.

In your 53 points there is no mention of saving. It is changes in the saving rate that causes changes in aggregate demand.

From counting variables and equations to complex edifices involving mid-point theorems there have been many attempts to prove GE. Each time someone points out a hole. Perhaps it is time to give up the attempt to square circles and accept that there is no GE.

LikeLike

Henry, I am not aware of the GET model that you were taught. I don’t understand how a GET model can “assume” that income is given. Resources, technology and preferences are given. Income is determined on the basis of resource endowments, technology (production functions) and preferences.

Again, there is no assumption that in GET production is on the PPF. That is an implication of utility maximization by households, profit maximization by firms, price taking behavior by all agents, the absence of externalities, etc. In order for this result to obtain, the system has to be solved for a set of equilibrium prices. At those equilibrium prices, full employment, and pareto optimality are implied, not assumed.

Hicks/Slutsky is a mathematical relationship that emerges from a constrained optimization exercise in which a household maximizes its utility subject to a budget constraint when the price of one of the consumption goods demanded by the household changes. That relationship which divides the effect of a price change into a substitution effect and an income effect resulting from the price change. The substitution effect is always negative, but the income effect can be positive or negative. Depending on the sign of income effect, goods can be classified as you indicate. You may or may not like it but the income effect is part of the analysis whereby the equilibrium price vector is determined because it is only the equilibrium price vector that entails that excess demands for all goods with a positive price be zero. Solving for the equilibrium price vector requires calculating excess demands at alternative prices in order to find the particular price vector that equates all excess demands equal to zero.

Finally, I’m sorry, Henry, but you are not the arbiter of what assumptions are allowed in a GET model.

philipji, Sorry, but I searched for it in the link that you sent and again was unable to find it.

LikeLike

David,

Your explanation is almost topsy turvy.

“I don’t understand how a GET model can “assume” that income is given.”

For optimization, an objective function is required (the PPC), to which a constraint is applied, the budget constraint, based on a given level of income. Without a given level of income optimization cannot be performed.

Relative price determination only makes sense in terms of an optimization.

The determination of an equilibrium point requires optimization.

“That is an implication of utility maximization by households, profit maximization by firms”

That is exactly what I am saying – at full employment.

” You may or may not like it but the income effect is part of the analysis whereby the equilibrium price vector is determined because it is only the equilibrium price vector that entails that excess demands for all goods with a positive price be zero. ”

Hicks/Slutsky applies to individual demand curves. It describes the composition of the price effect AT A GIVEN LEVEL OF INCOME. I did say the income effect is part of the analysis but it is given by the relationship between the price of the good and a given level of income (otherwise it is nonsensical.)

“Finally, I’m sorry, Henry, but you are not the arbiter of what assumptions are allowed in a GET model.”

I didn’t say I was. But the standard GET model does have specified assumptions.

LikeLike

Henry,

The objective functions that are optimized are household utility functions and firms profit functions. The PPC may be inferred from the assumed production technologies and the resource endowments underlying the model, but there is no PPC function in a GET model merely production functions and resource endowments that determine the supplies offered by firms as functions of output and input prices. Again, you aren’t correctly specifying a GE model is specified or how it is solved.

And again, GET does not assume that resources are fully employed in equilibrium. It is a theorem that GET proves given the more basic assumptions that the model assumes. You might as well say that geometry assumes that the triangles angles of a triangle sum to 180 degrees or that it assumes that the sum of the squares of two sides of a triangle equal the square of the hypotenuse.

LikeLike

David,

“Again, you aren’t correctly specifying a GE model is specified or how it is solved.”

The theory isn’t called the General Equilibrium Theory for no reason.

What you describe above is the partial equilibrium approach. Walras’ equations are not formulated in partial equilbrium terms. General equilibrium can be expressed as in the form of a PPF and a BC. This is Microeconomics 101. I think your distinction is trivial.

“GET does not assume that resources are fully employed in equilibrium. It is a theorem that GET proves given the more basic assumptions that the model assumes.”

Again this is a trivial distinction. Equilibrium will always be found on the PPF, that is where there is full employment of resources.

LikeLike

Henry, Sorry to be blunt, but you really don’t seem to grasp the difference between general equilibrium and partial equilibrium. In addition, a budget constraint relates to individual households not to an entire economy. It is the PPF that occupies the role of a budget constraint for a macro model. Under assumptions that would allow for the construction of a community social welfare function (basically the assumptions that make a representative agent a coherent, if not very useful, assumption) it is the PPF that would play the role of that a budget constraint plays for a household. Finally, I really don’t need to be instructed about microeconomics 101.

LikeLike

David,

“I really don’t need to be instructed about microeconomics 101.”

I have overstepped the mark.

I apologize.

I will leave it at that.

LikeLike

Henry, We all get carried away sometimes. No apology necessary.

LikeLike