Having explained in my previous post why the price-specie-flow mechanism (PSFM) is a deeply flawed mischaracterization of how the gold standard operated, I am now going to discuss two important papers by McCloskey and Zecher that go explain in detail the conceptual and especially the historical shortcomings of PSFM. The first paper (“How the Gold Standard Really Worked”) was published in the 1976 volume edited by Johnson and Frenkel, The Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments; the second paper, (“The Success of Purchasing Power Parity: Historical Evidence and its Relevance for Macroeconomics”) was published in a 1984 NBER conference volume edited by Schwartz and Bordo, A Retrospective on the Classical Gold Standard 1821-1931. I won’t go through either paper in detail, but I do want to mention their criticisms of The Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, by Friedman and Schwartz and Friedman’s published response to those criticisms in the Schwartz-Bordo volume. I also want to register a mild criticism of an error of omission by McCloskey and Zecher in failing to note that, aside from the role of the balance of payments under the gold standard in equilibrating the domestic demand for money with the domestic supply of money, there is also a domestic mechanism for equilibrating the domestic demand for money with the domestic supply; it is only when the domestic mechanism does not operate that the burden for adjustment falls upon the balance of payments. I suspect that McCloskey and Zecher would not disagree that there is a domestic mechanism for equilibrating the demand for money with the supply of money, but the failure to spell out the domestic mechanism is still a shortcoming in these two otherwise splendid papers.

McCloskey and Zecher devote a section of their paper to the empirical anomalies that beset the PSFM.

If the orthodox theories of the gold standard are incorrect, it should be possible to observe signs of strain in the literature when they are applied to the experiences of the late nineteenth century. This is the case. Indeed, in the midst of their difficulties in applying the theories earlier observers have anticipated most of the elements of the alternative theory proposed here.

On the broadest level it has always been puzzling that the gold standard in its prime worked so smoothly. After all, the mechanism described by Hume, in which an initial divergence in price levels was to be corrected by flows of gold inducing a return to parity, might be expected to work fairly slowly, requiring alterations in the money supply and, more important, in expectations concerning the level and rate of change of prices which would have been difficult to achieve. The actual flows of gold in the late nineteenth century, furthermore, appear too small to play the large role assigned to them. . . . (pp. 361-62)

Later in the same section, they criticize the account given by Friedman and Schwartz of how the US formally adopted the gold standard in 1879 and its immediate aftermath, suggesting that the attempt by Friedman and Schwartz to use PSFM to interpret the events of 1879-81 was unsuccessful.

The behavior of prices in the late nineteenth century has suggested to some observers that the view that it was gold flows that were transmitting price changes from one country to another is indeed flawed. Over a short period, perhaps a year or so, the simple price-specie-flow mechanism predicts an inverse correlation in the price levels of two countries interacting with each other on the gold standard. . . . Yet, as Triffin [The Evolution of the International Monetary System, p. 4] has noted. . . even over a period as brief as a single year, what is impressive is “the overeall parallelism – rather than divergence – of price movements, expressed in the same unit of measurement, between the various trading countries maintaining a minimum degree of freedom of trade and exchange in their international transactions.

Over a longer period of time, of course, the parallelism is consistent with the theory of the price-specie-flow. In fact, one is free to assume that the lags in its mechanism are shorter than a year, attributing the close correlations among national price levels within the same year to a speedy flow of gold and a speedy price change resulting from the flow rather than to direct and rapid arbitrage. One is not free, however, to assume that there were no lags at all; in the price-specie-flow theory inflows of gold must precede increase in prices by at least the number of months necessary for the money supply to adjust to the new gold and for the increased amount of money to have an inflationary effect. The American inflation following the resumption of specie payments in January 1879 is a good example. After examining the annual statistics on gold flows and price levels for the period, Friedman and Schwartz [Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, p. 99] concluded that “It would be hard to find a much neater example in history of the classical gold-standard mechanism in operation.” Gold flowed in during 1879, 1880, and 1881 and American prices rose each year. Yet the monthly statistics on American gold flows and price changes tell a very different story. Changes in the Warren and Pearson wholesale price index during 1879-81 run closely parallel month by month with gold flows, rising prices corresponding to net inflows of gold. There is no tendency for prices to lag behind a gold flow and some tendency for them to lead it, suggesting not only the episode is an especially poor example of the price-specie flow theory in operation, but also that it might well be a reasonably good one of the monetary theory. (pp. 365-66)

Now let’s go back and see exactly what Friedman and Schwartz said about the episode in the Monetary History. Here is how they describe the rapid expansion starting with the resumption of convertibility on January 1, 1879:

The initial cyclical expansion from 1879 to 1882 . . . was characterized by an unusually rapid rise in the stock of money and in net national product in both current and constant prices. The stock of money rose by over 50 per cent, net national product in current prices over 35 per cent, and net national product in constant prices nearly 25 per cent. . . . (p. 96)

The initial rapid expansion reflected a combination of favorable physical and financial factors. On the physical side, the preceding contraction had been unusually protracted; once it was over, there tended to be a vigorous rebound; this is a rather typical pattern of reaction. On the financial side, the successful achievement of resumption, by itself, eased pressure on the foreign exchanges and permitted an internal price rise without external difficulties, for two reasons: first, because it eliminated the temporary demand for foreign exchange on the part of the Treasury to build up its gold reserve . . . second because it promoted a growth in U.S. balances held by foreigners and a decline in foreign balances held by U.S. residents, as confidence spread that the specie standard would be maintained and that the dollar would not depreciate again. (p. 97)

The point about financial conditions that Friedman and Schwartz are making is that, in advance of resumption, the US Treasury had been buying gold to increase reserves with which to satisfy potential demands for redemption once convertibility at the official parity was restored. The gold purchases supposedly forced the US price level to drop further (at the official price of gold, corresponding to a $4.86 dollar/sterling exchange rate) than it would have fallen if the Treasury had not been buying gold. (See quotation below from p. 99 of the Monetary History). Their reasoning is that the additional imports of gold ultimately had to be financed by a corresponding export surplus, which required depressing the US price level below the price level in the rest of the world sufficiently to cause a sufficient increase in US exports and decrease of US imports. But the premise that US exports could be increased and US imports could be decreased only by reducing the US price level relative to the rest of the world is unfounded. The incremental export surplus required only that total domestic expenditure be reduced, thereby allowing an incremental increase US exports or reduction in US imports. Reduced US spending would have been possible without any change in US prices. Friedman and Schwartz continue:

These forces were powerfully reinforced by accidents of weather that produced two successive years of bumper crops in the United States and unusually short crops elsewhere. The result was an unprecedentedly high level of exports. Exports of crude foodstuffs, in the years ending June 30, 1889 and 1881, reached levels roughly twice the average of either the preceding or the following year five years. In each year they were higher than in any preceding year, and neither figure was again exceeded until 1892. (pp. 97-98)

This is a critical point, but neither Friedman and Schwartz nor McCloskey and Zecher in their criticism seem to recognize its significance. Crop shortages in the rest of the world must have caused a substantial increase in grain and cotton prices, but Friedman and Schwartz provide no indication of the magnitudes of the price increases. At any rate, the US was then still a largely agricultural economy, so a substantial rise in agricultural prices determined in international markets would imply an increase in an index of US output prices relative to an index of British output prices reflecting both a shifting terms of trade in favor of the US and a higher share of total output accounted for by agricultural products in the US than in Britain. That shift, and the consequent increase in US versus British price levels, required no divergence between prices in the US and in Britain, and could have occurred without operation of the PSFM. Ignoring the terms-of-trade effect after drawing attention to the bumper crops in the US and crop failures elsewhere was an obvious error in the narrative provided by Friedman and Schwartz. With that in mind, let us return to their narrative.

The resulting increased demand for dollars meant that a relatively higher price level in the United States was consistent with equilibrium in the balance of payments.

Friedman and Schwartz are assuming that a demand for dollars under a fixed-exchange-rate regime can be satisfied only by through an incremental adjustment in exports and imports to induce an offsetting flow of dollars. Such a demand for dollars could also be satisfied by way of appropriate banking and credit operations requiring no change in imports and exports, but even if the demand for money is satisfied through an incremental adjustment in the trade balance, the implicit assumption that an adjustment in the trade balance requires an adjustment in relative price levels is totally unfounded; the adjustment in the trade balance can occur with no divergence in prices, such a divergence being inconsistent with the operation of international arbitrage.

Pending the rise in prices, it led to a large inflow of gold. The estimated stock of gold in the United States rose from $210 million on June 30, 1879, to $439 million on June 30, 1881.

The first sentence is difficult to understand. Having just asserted that there was a rise in US prices, why do Friedman and Schwartz now suggest that the rise in prices has not yet occurred? Presumably, the antecedent of the pronoun “it” is the demand for dollars, but why is the demand for dollars conditioned on a rise in prices? There are any number of reasons why there could have been an inflow of gold into the United States. (Presumably, higher than usual import demand could have led to a temporary drawdown of accumulated liquid assets, e.g., gold, in other countries to finance their unusually high grain imports. Moreover, the significant wealth transfer associated with a sharply improving terms of trade in favor of the US would have led to an increased demand for gold, either for real or monetary uses. More importantly, as banks increased the amount of deposits and banknotes they were supplying to the public, the demand of banks to hold gold reserves would have also increased.)

In classical gold-standard fashion, the inflow of gold helped produce an expansion in the stock of money and in prices. The implicit price index for the U.S. rose 10 per cent from 1879 to 1882 while a general index of British prices was roughly constant, so that the price level in the United States relative to that in Britain rose from 89.1 to 96.1. In classical gold-standard fashion, also, the outflow of gold from other countries produced downward pressure on their stock of money and their prices.

To say that the inflow of gold helped produce an expansion in the stock of money and in prices is simply to invoke the analytically empty story that gold reserves are lent out to the public, because the gold is sitting idle in bank vaults just waiting to be put to active use. But gold doesn’t just wind up sitting in a bank vault for no reason. Banks demand it for a purpose; either they are legally required to hold the gold or they find it more useful or rewarding to hold gold than to hold alternative assets. Banks don’t create liabilities payable in gold because they are holding gold; they hold gold because they create liabilities payable in gold; creating liabilities legally payable in gold may entail a legal obligation to hold gold reserves, or create a prudential incentive to keep some gold on hand. The throw-away references made by Friedman and Schwartz to “classical gold-standard fashion” is just meaningless chatter, and the divergence between the US and the British price indexes between 1879 and 1882 is attributable to a shift in the terms of trade of which the flow of gold from Britain to the US was the effect not the cause.

The Bank of England reserve in the Banking Department declined by nearly 40 percent from mid-1879 to mid-1881. In response, Bank rate was raised by steps from 2.5 per cent in April 1881 to 6 per cent in January 1882. The resulting effects on both prices and capital movements contributed to the cessation of the gold outflow to the U.S., and indeed, to its replacement by a subsequent inflow from the U.S. . . . (p. 98)

The only evidence about the U.S. gold stock provided by Friedman and Schwartz is an increase from $210 million to $439 million between June 30, 1879 to June 30, 1881. They juxtapose that with a decrease in the gold stock held by the Bank of England between mid-1879 and mid-1881, and an increase in Bank rate from 2.5% to 6%. Friedman and Schwartz cite Hawtrey’s Century of Bank Rate as the source for this fact (the only citation of Hawtrey in the Monetary History). But the increase in Bank rate from 2.5% did not begin till April 28, 1881, Bank rate having fluctuated between 2 and 3% from January 1878 to April 1881, two years and three months after the resumption. Discussing the fluctuations in the gold reserve of the Bank England in 1881, Hawtrey states:

The exports of gold had abated in the earlier part of the year, but set in again in August, and Bank rate was raised to 4 per cent. On the 6th of October it was put up to 5 per cent and on the 30th January, 1882, to 6.

The exports of gold had been accentuated in consequence of the crisis in Paris in January, 1882, resulting from the failure of the Union Generale. The loss of gold by export stopped almost immediately after the rise to 6 per cent. In fact the importation into the United States was ceasing, in consequence partly of the silver legislation which went far to satisfy the need for currency with silver certificates. (p. 102)

So it’s not at all clear from the narrative provided by Friedman and Schwartz to what extent the Bank of England, in raising Bank rate in 1881, was responding to the flow of gold to the United States, and they certainly do not establish that price-level changes between 1879 to 1881 reflected monetary, rather than real, forces. Here is how Friedman and Schwartz conclude their discussion of the effects of the resumption of US gold convertibility.

These gold movements and those before resumption have contrasting economic significance. As mentioned in the preceding chapter, the inflow into the U.S. before resumption was deliberately sought by the Treasury and represented an increased demand for foreign exchange. It required a surplus in the balance of payments sufficient to finance the gold inflow. The surplus could be generated only by a reduction in U.S. prices relative to foreign prices or in the price of the U.S. dollar relative to foreign currencies and was, in fact, generated by a relative reduction in U.S. prices. The gold inflow was, as it were, the active element to which the rest of the balance of payments adjusted.

This characterization of the pre-resumption deflationary process is certainly correct insofar as refers to the necessity of a deflation in US dollar prices for the dollar to appreciate to allow convertibility into gold at the 1861 dollar price of gold and dollar/sterling exchange rate. It is not correct insofar as it suggests that beyond the deflation necessary to restore purchasing power parity, a further incremental deflation was required to finance the Treasury’s demand for foreign exchange

After resumption, on the other hand, the active element was the increased demand for dollars resulting largely from the crop situation. The gold inflow was a passive reaction which temporarily filled the gap in payments. In its absence, there would have had to be an appreciation of the dollar relative to other currencies – a solution ruled out by the fixed exchange rate under the specie standard – or a more rapid [sic! They meant “less rapid”] rise in internal U.S. prices. At the same time, the gold inflow provided the basis and stimulus for an expansion in the stock of money and thereby a rise in internal prices at home and downward pressure on the stock of money and price abroad sufficient to bring an end to the necessity for large gold inflows. (p. 99)

This explanation of the causes of gold movements is not correct. The crop situation was a real, not a monetary, disturbance. We would now say that there was a positive supply shock in the US and a negative supply shock in the rest of the world, causing the terms of trade to shift in favor of the US. The resulting gold inflow reflected an increased US demand for gold induced by rapid economic growth and the improved terms of trade and a reduced demand to hold gold elsewhere to finance a temporary excess demand for grain. The monetary demand for gold would have also increased as a result of an increasing domestic demand for money. An increased demand for money could induce an inflow of gold to be minted into coin or to be held as legally required reserves for banknotes or to be held as bank reserves for deposits. The rapid increase in output and income, fueled in part by the positive supply shock and the improving terms of trade, would normally be expected to increase the demand to hold money. If the gold inflow was the basis, or the stimulus, for an expansion of the money stock, then increases in the gold stock should have preceded increases in the money stock. But as I am going to show, Friedman himself later provided evidence showing that in this episode the money stock at first increased more rapidly than the gold stock. And just as price increases and money expansion in the US were endogenous responses to real shocks in output and the terms of trade, adjustments in the stock of money and prices abroad were not the effects of monetary disturbances but endogenous monetary adjustments to real disturbances.

Let’s now turn to the second McCloskey-Zecher paper in which they returned to the 1879 resumption of gold convertibility by the US.

In an earlier paper (1976, p. 367) we reviewed the empirical anomalies in the price-specie-flow mechanism. For instance, we argued that Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz misapplied the mechanism to an episode in American history. The United States went back on the gold standard in January 1879 at the pre-Civil War parity. The American price level was too low for the parity, allegedly setting the mechanism in motion. Over the next three years, Friedman and Schwartz argued from annual figures, gold flowed in and the price level rose just as Hume would have had it. They conclude (1963, p. 99) that “it would be hard to find a much neater example in history of the classical gold-standard mechanism in operation.” On the contrary, however, we believe it seems much more like an example of purchasing-power parity and the monetary approach than of the Humean mechanism. In the monthly statistics (Friedman and Schwartz confined themselves to annual data), there is no tendency for price rises to follow inflows of gold, as they should in the price-specie-flow mechanism; if anything, there is a slight tendency for price rises to precede inflows of gold, as they would if arbitrage were shortcutting the mechanism and leaving Americans with higher prices directly and a higher demand for gold. Whether or not the episode is a good example of the monetary theory, it is a poor example of the price-specie-flow mechanism. (p. 126)

Milton Friedman, a discussant at the conference at which McCloskey and Zecher presented their paper, submitted his amended remarks about the paper which were published in the volume along with comments of the other discussant, Robert E. Lipsey, and a transcript of the discussion of the paper by those in attendance. Here is Friedman’s response.

[McCloskey and Zecher] quote our statement that “it would be hard to find a much neater example in history of the classical gold-standard mechanism in operation” (p. 99). Their look at that episode on the basis of monthly data is interesting and most welcome, but on closer examination it does not, contrary to their claims, contradict our interpretation of the episode. McCloskey and Zecher compare price rises to inflows of gold, concluding, “In the monthly statistics … there is no tendency for price rises to follow inflows of gold . . . ; if anything, there is a slight tendency for price rises to precede inflows of gold, as they would if arbitrage were shortcutting the mechanism.”

Their comparison is the wrong one for determining whether prices were reacting to arbitrage rather than reflecting changes in the quantity of money. For that purpose the relevant comparison is with the quantity of money. Gold flows are relevant only as a proxy for the quantity of money. (p. 159)

I don’t understand this assertion at all. Gold flows are not simply a proxy for the quantity of money, because the whole premise of the PSFM is, as he and Schwartz assert in the Monetary History, that gold flows provide the “basis and stimulus for” an increase in the quantity of money.

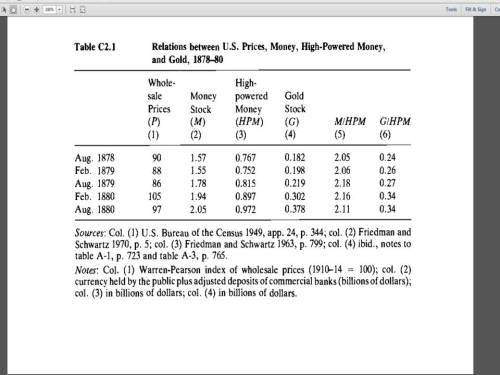

If we compare price rises with changes in the quantity of money directly, a very different picture emerges than McCloskey and Zecher draw (see table C2.1). Our basic estimates of the quantity of money for this period are for semiannual dates, February and August. Resumption took effect on 1 January 1879. From August 1878 to February 1879, the money supply declined a trifle, continuing a decline that had begun in 1875 in final preparation for resumption. From February 1879 to August 1879, the money supply rose sharply, according to our estimates, by 15 percent. The Warren-Pearson monthly wholesale price index fell in the first half of 1879, reflecting the earlier decline in the money stock. It started its sharp rise in September 1879, or at least seven months later than the money supply.

Again, I don’t understand Friedman’s argument. The quantity of money began to rise after the resumption. In fact, Friedman’s own data show that in the six months from February to August of 1879, the quantity of money rose by 14.8% and the gold stock by 10.6%, with no effect on the price level. Friedman asserts that the price level didn’t start to rise until September, eight or nine months after the resumption in January. But it seems quite plausible that the fall harvest would have been the occasion for the effects of crop failures on grain prices to begin to have any effect on wholesale prices. So Friedman’s own evidence undercuts his assertion that the increase in the quantity of money was what was causing US prices to rise.

As to gold, the total stock of gold, as well as gold held by the Treasury, had been rising since 1877 as part of the preparation for resumption. But it had been rising at the expense of other components of high-powered money, which actually fell slightly. However, the decline in the money stock before 1879 had been due primarily to a decline in the deposit-currency ratio and the deposit-reserve ratio. After successful resumption, both ratios rose, which enabled the stock of money to rise despite no initial increase in gold flows. The large step-up in gold inflows in the fall of 1879, to which McCloskey and Zecher call attention, was mostly absorbed in raising the fraction of high-powered money in the form of gold rather than in speeding up monetary growth.

I agree with Friedman that the rapid increase in gold flows starting the fall of 1879 probably had little to do with the increase in the US price level, that increase reflecting primarily the terms-of-trade effect of rising agricultural prices, not a divergence between prices in the US and prices elsewhere in the world. But that does not justify Friedman’s self-confident reiteration of the conclusion reached in the Monetary History that it would be hard to find a much neater example in history of the classical gold standard mechanism in operation. On the contrary, I see no evidence at all that “the classical gold standard mechanism” aka PSFM had anything to do with the behavior of prices after the resumption.

I have a basic question.

Across much of your writing on this subject, there seems to be an association of gold flows under the gold standard with the settlement of a trade imbalance.

I don’t understand this.

Why could ultimate balancing of the trade position not consist of a mix of gold flows, bonds, money balances, etc.?

I suppose I could understand an exclusive 1:1 connection assumed in the case of Hume’s 1752 paper, where presumably the international payments system was not so developed.

But surely even in the late 1800’s there was such a thing as capital flows consisting of bonds and money balances? Such items would provide payments balancing options apart from gold. If so, why the apparent 1:1 assumption of gold flows with settlement of the trade balance?

If that assumption is not intended, then I think some occasional reference to the demand for gold in the context of such a composite mix would be helpful. I’ve never noticed any such reference.

That said, there has been occasional reference to foreign exchange reserves apart from gold reserves, which itself seem to contradict the assumption I just suggested. But my point is more general – surely additional types of capital flows were possible as an offset to a trade balance, including capital flows of private sector bonds and money holdings that did not affect the government gold and FX reserve positions.

This question is in the same vein as the one I asked previously on what determines gold flows. My question is intended to probe beyond the categories of supply and demand – I meant it the context of flows (and resulting changes in balance sheets) which must by (accounting and operational) logic offset in their entirety a trade imbalance.

LikeLike

Hi David,

Can you recommend any papers or books that give a good mathematical model of the gold standard, perhaps under different conditions, since I know that there are different “kinds” of gold standards? I’ve seen a number of them, but now that I read your blog I no longer know which one is correct. Which one, in your opinion, should be the final word on the subject?

LikeLike

To follow up on JKH’s comment, the international monetary system changed greatly between the time of Hume’s essay (1752) and the period considered the heyday of the international gold standard, 1880-1914. In Hume’s day there were few banks: the Bank of North America, the first bank in the United States and I believe anywhere in the New World, was not founded until 1782. Long-distance transportation was only by sailing ship. Long-distance communication was likewise only by sailing ship. It took the better part of a year to get a reply to a message sent from London to Australia.

For those reasons, arbitrage outside of northwestern Europe was sluggish. Sudden large rises and falls in local supplies of gold and silver coins were common and commonly remarked. A ship might bring a great quantity of coin to buy local goods, producing an abundance of currency, or it might sell goods for coin, taking away currency and reducing the supply quite noticeably, leaving people to try various expedients until the next ship came along, which might be as much as a year later. Robert Chalmers’s 1893 book A History of Currency in the British Colonies, which you can find free online, gives some idea of the consequences for the working of monetary systems in many parts of the world.

Hume’s simplified description was not too far from the reality of most of the globe in his time. His later critics, taking for granted the steamship, the railroad, the telegraph, banking, and securities markets, have in effect criticized Hume for not understanding how the international monetary system would develop long after his death.

LikeLike

Thanks to Kurt Shuler for his comment above.

Also – Ramanan (‘Concerted Action’ blogger) pointed me to this interesting paper:

http://www.academia.edu/887075/The_Gold_Standard_and_Center-Periphery_Interactions

From that paper:

“One important limitation of Hume’s model to characterize the working of the classic gold standard system of the end of nineteen century is the assumption that only gold coins circulate, and that there are no other capital flows. In reality, the central banks of the countries involved in the gold standard did not allow gold to move freely from one country to another … monetary authorities resorted to the sales and purchases of foreign exchange against domestic currency in order to maintain the exchange rate within the limits of the gold points … private capital flows were also crucially relevant for the working of the gold standard. So that, in contrast with Hume’s model, the gold standard system was characterized by the limited amount of gold coin circulation. The consensus has been that under the pre-1914 system those capital movements had primarily an equilibrating role in the balance of payments … capital flows benignly substitute for flows of gold specie (Eichengreen, 1996) … the relative control that the Bank of England had on the balance of payments through the manipulation of the exogenous rate of interest … in fact the ability to control capital flows, which is ultimately dependent on the international role of the pound sterling and the role of the City as the main financial center of the world, allowed Britain to stay on a gold standard for more than a century … Britain, and to a lesser degree the other central countries, could borrow in international markets in their own currencies. Higher interest rates then actually worked in bringing the needed capital inflows.”

As your post suggests, the price level reacted as a result of an arbitrage process rather than PSFM. But it seems additionally important to understand that gold flows in any event simply did not occur in the relative magnitude implied by PSFM. This second point seems to be a matter of empirical observation and record – capital flows and interest rates that affected those capital flows were apparently very important from 1880 to 1914.

So PSFM was apparently inapplicable in terms of both price level determination and flow of funds composition, the latter in a very material way.

These two aspects are probably connected in an interesting way. Its seems intuitive that the capital flow options would make the arbitrage process even more “efficient”.

But I think it is an important distinction:

FSFM was inapplicable – not just because of the existence of arbitrage – but because of the existence of arbitrage in the context of a complex capital flow menu that consisted of much more than just gold flows.

LikeLike

sorry

thanks to Kurt Schuler (spelling)

and typo – PSFM in final paragraph

LikeLike

A note: in my comment, for clarity I should have used, say, India rather than Australia as an example of a distant land, since Europeans had not yet discovered Australia at the time Hume wrote his essay. I had in mind the situation 50 or even 100 years later, when Australia was part of the global economy but before the telegraph had shrunk the time necessary for communications between the ends of the earth from months to hours.

LikeLike

Again my apologies for the long delay in my response to these comments.

JKH, I agree that gold need be used to settle trade imbalances, but that is the simple story underlying the naïve PSFM and the theory of the Bank Charter Act. But you are right that the development of financial markets soon rendered the old story an anachronism. Ricardo was one of the earliest writers to point out that it would be wasteful to ship gold when the balance could be settled by a financial transaction. Central banks are in a position to affect the size and the settlement of trade imbalances by their influence over domestic money markets and thereby can control the size and composition of the their own balance sheets. In general the mechanism that central banks would use to control the size of their balance sheet was their lending rate to banks.

Ilya, The only paper that comes to mind is a 1979 paper by Barro “Money and the Price Level under the Gold Standard,” published I think in the Journal of Monetary Economics. I once thought that it wasn’t a good model of the gold standard, but when I went back and looked at it again, it seemed to me better than I thought it was originally. You might also consult my paper “A Reinterpretation of Classical Monetary Theory” in which I presented what I thought was a neat little composite diagram based on the model developed by Earl Thompson which can be found in his paper “The Theory of Money and Income Consistent with Orthodox Value Theory,” published in Trade Stability and Macroeconomics: Essays in Honor of Lloyd Metzler.

Kurt, Thanks for your comment. I think that criticism of Hume began already as early as Thornton’s 1802 volume on Bank Credit of Great Britain. I have also suggested, following David Laidler, that Adam Smith who faithfully reproduced the Humean version in his 1763 Lectures on Jurisprudence omitted any mention of the Humean PSFM in his 1776 account of international adjustment in the Wealth of Nations.

JKH, Thanks for the link. I agree that gold flows were simply insufficient to account for the effects attributed to them by the PSFM. That is a point that has been made many times over the years and which McCloskey and Zecher make as well. But I agree completely with what you are saying.

LikeLike