I don’t know who Amar Bhide (apologies for not being able to insert an accent over the “e” in his last name) is, but Edmund Phelps is certainly an eminent economist and a deserving recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in economics. Unfortunately, Professor Phelps attached his name to an op-ed in Wednesday’s Wall Street Journal, co-authored with Bhide, consisting of little more than a sustained, but disjointed, rant about the Fed and central banking. I am only going to discuss that first part of the op-ed that touches on the monetary theory of increasing the money supply through open-market operations, and about the effect of that increase on inflation and inflation expectations. Bhide and Phelps not only get the theory wrong, they seem amazingly oblivious to well-known facts that flatly contradict their assertions about monetary policy since 2008. Let’s join them in their second paragraph.

Monetary policy might focus on the manageable task of keeping expectations of inflation on an even keel—an idea of Mr. Phelps’s [yes that same Mr. Phelps whose name appears as a co-author] in 1967 that was long influential. That would leave businesses and other players to determine the pace of recovery from a recession or of pullback from a boom.

Nevertheless, in late 2008 the Fed began its policy of “quantitative easing”—repeated purchases of billions in Treasury debt—aimed at speeding recovery. “QE2” followed in late 2010 and “QE3” in autumn 2012.

One can’t help wondering what planet Bhide and Phelps have been dwelling on these past four years. To begin with, the first QE program was not instituted until March 2009 after the target Fed funds rate had been reduced to 0.25% in December 2008. Despite a nearly zero Fed funds rate, asset prices, which had seemed to stabilize after the September through November crash, began falling sharply again in February, the S&P 500 dropping from 869.89 on February 9 to 676.53 on March 9, a decline of more than 20%, with inflation expectations as approximated, by the TIPS spread, again falling sharply as they had the previous summer and fall.

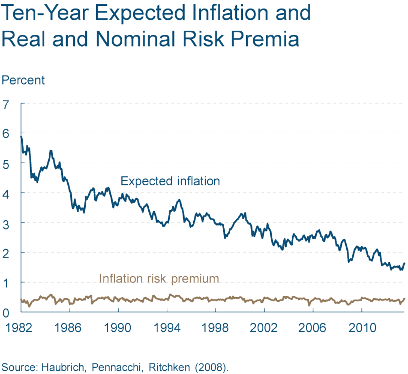

Apart from their confused chronology, their suggestion that the Fed’s various quantitative easings have somehow increased inflation and inflation expectations is absurd. Since 2009, inflation has averaged less than 2% a year – one of the longest periods of low inflation in the entire post-war era. Nor has quantitative easing increased inflation expectations. The TIPS spread and other measures of inflation expectations clearly show that inflation expectations have fluctuated within a narrow range since 2008, but have generally declined overall.

The graph below shows the estimates of the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank of 10-year inflation expectations since 1982. The chart shows that the latest estimate of expected inflation, 1.65%, is only slightly above its the low point, reached in March, over the past 30 years. Thus expected inflation is now below the 2% target rate that the Fed has set. And to my knowledge Professor Phelps has never advocated targeting an annual inflation rate less than 2%. So I am unable to understand what he is complaining about.

Bhide and Phelps continue:

Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said in November 2010 that this unprecedented program of sustained monetary easing would lead to “higher stock prices” that “will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending.”

It is doubtful, though, that quantitative easing boosted either wealth or confidence. The late University of Chicago economist Lloyd Metzler argued persuasively years ago that a central-bank purchase, in putting the price level onto a higher path, soon lowers the real value of household wealth—by roughly the amount of the purchase, in his analysis. (People swap bonds for money, then inflation occurs, until the real value of money holdings is back to where it was.)

There are three really serious problems with this passage. First, and most obvious to just about anyone who has not been asleep for the last four years, central-bank purchases have not put the price level on a higher path than it was on before 2008; the rate of inflation has clearly fallen since 2008. Or would Bhide and Phelps have preferred to allow the deflation that briefly took hold in the fall of 2008 to have continued? I don’t think so. But if they aren’t advocating deflation, what exactly is their preferred price level path? Between zero and 1.5% perhaps? Is their complaint that the Fed has allowed inflation to be a half a point too high for the last four years? Good grief.

Second, Bhide and Phelps completely miss the point of the Metzler paper (“Wealth, Saving and the Rate of Interest”), one of the classics of mid-twentieth-century macroeconomics. (And I would just mention as an aside that while Metzler was indeed at the University of Chicago, he was the token Keynesian in the Chicago economics department in 1940s and early 1950s, until his active career was cut short by a brain tumor, which he survived, but with some impairment of his extraordinary intellectual gifts. Metzler’s illness therefore led the department to hire an up-and-coming young Keynesian who had greatly impressed Milton Friedman when he spent a year at Cambridge; his name was Harry Johnson. Unfortunately Friedman and Johnson did not live happily ever after at Chicago.) The point of the Metzler paper was to demonstrate that monetary policy, conducted via open-market operations, could in fact alter the real interest rate. Money, on Metzler’s analysis, is not neutral even in the long run. The conclusion was reached via a comparative-statics exercise, a comparison of two full-employment equilibria — one before and one after the central bank had increased the quantity of money by making open-market purchases.

The motivation for the exercise was that some critics of Keynes, arguing that deflation, at least in principle, could serve as a cure for involuntary unemployment — an idea that Keynes claimed to have refuted — had asserted that, because consumption spending depends not only on income, but on total wealth, deflation, by increasing the real value of the outstanding money stock, would actually make households richer, which would eventually cause households to increase consumption spending enough to restore full employment. Metzler argued that if consumption does indeed depend on total wealth, then, although the classical proposition that deflation could restore full employment would be vindicated, another classical proposition — the invariance of the real rate of interest with respect to the quantity of money — would be violated. So Metzler’s analysis — a comparison of two full-employment equilbria, the first with a lower quantity of money and a higher real interest rate and the second with a higher quantity of money and lower real interest rate – has zero relevance to the post-2008 period, in which the US economy was nowhere near full-employment equilibrium.

Finally, Bhide and Phelps, mischaracterize Metzler’s analysis. Metzler’s analysis depends critically on the proposition that the reduced real interest rate caused by monetary expansion implies an increase in household wealth, thereby leading to increased consumption. It is precisely the attempt to increase consumption that, in Metzler’s analysis, entails an inflationary gap that causes the price level to rise. But even after the increase in the price level, the real value of household assets, contrary to what Bhide and Phelps assert, remains greater than before the monetary expansion, because of a reduced real interest rate. A reduced real interest rate implies an increased real value of the securities retained by households.

Under Metzler’s analysis, therefore, if the starting point is a condition of less than full employment, increasing the quantity of money via open-market operations would tend to increase not only household wealth, but would also increase output and employment relative to the initial condition. So it is also clear that, on Metzler’s analysis, apparently regarded by Bhide and Phelps as authoritative, the problem with Fed policy since 2008 is not that it produced too much inflation, as Bhide and Phelps suggest, but that it produced too little.

If it seems odd that Bhide and Phelps could so totally misread the classic paper whose authority they invoke, just remember this: in the Alice-in-Wonderland world of the Wall Street Journal editorial page, things aren’t always what they seem.

HT: ChargerCarl

Much of the first half of the essay was Ned’s and I will leave it to him to respond to the specifics if he wants to but let me say that our criticism had absolutely nothing to do with increasing inflation or inflationary expectations. In fact Ned had a line that was edited out that was implicitly critical of the Fed’s failure to counter the *decline* in inflationary expectations.

My own complaint can be summarized as follows: it is wrong to even attempt to pump up stock prices that disproportionately benefit the top 1% of the population while driving down the interest grandapa and grandma receive on their CDs in the name of an tenuous theory and in the face of widespread opposition from the public (whether they be of the rightist or leftist persuasion).

(I also personally find it hard to take seriously low single digit changes in the measured price level given huge differences in what different people consume and the ever changing set of goods and services available for consumption)

LikeLike

Amar,

“My own complaint can be summarized as follows: it is wrong to even attempt to pump up stock prices that disproportionately benefit the top 1% of the population while driving down the interest grandapa and grandma receive on their CDs in the name of an tenuous theory and in the face of widespread opposition from the public (whether they be of the rightist or leftist persuasion).”

Allow me to respond. First it worked.

Click to access z1.pdf

Page 115

2007: U. S. Household Assets – $81.1 Trillion, U. S. Household Liabilities – $14.2 Trillion

2008: U. S. Household Assets – $68.3 Trillion, U. S. Household Liabilities – $14.1 Trillion

2013: U. S. Household Assets – $83.7 Trillion, U. S. Household Liabilities – $13.4 Trillion

Second, you can make the very valid argument that propping up stock prices may not accomplish the Fed’s primary goals of full employment and low inflation. But because fiscal policy is so screwed up on both expenditures (unproductive wars) and tax incentives (crony capitalism), monetary policy does what it can ON A MACRO LEVEL.

If you want to start arguing about fairness and how the little guy is getting screwed, then the best place to start would be fiscal policy NOT monetary policy.

LikeLike

What DO you have against grandma and grandpa, David? Not to mention the savings deposits of their grandchildren. Won’t somebody please think of the children?!

Anyway, if we can take one lesson from the Japanese experience and the experience of the US, UK and EZ over the last 5 years, it’s that tight money is the strongest guarantee of low interest rates. If you want higher interest rates for grandma and grandpa, then you should want looser monetary policy.

“In fact Ned had a line that was edited out that was implicitly critical of the Fed’s failure to counter the *decline* in inflationary expectations.”

The WSJ edited that out? I’m shocked.

LikeLike

Changes in (*estimates* of) total wealth do not rebut the charge of perverse redistribution from grandma and grandpa to the top 1%. Nor does bringing up bad fiscal policies.

W. Peden: you know as well as I that high rates with high inflation don’t do savers of modest means any good. In any event I’d prefer a monetary policy that is neutral to interests and to accomplish that instruments that are less top down and governance structures that are less centralized.

LikeLike

Amar Bhide,

So are you objecting to low nominal rates or low real rates? If your contention is that the Fed is creating a permanent reduction in real interest rates that hurts depositors, then you have to present a model where the Fed can control real interest rates in equilibrium. If your contention is that the Fed is lowering nominal interest rates at the expense of those who save via deposits rather than stocks or bonds, then you should want a robust monetary stimulus because low nominal rates right now are symptoms of tight monetary policy.

Also, if you’re making an egalitarian case against QE, then you at least have to mention that the top 1% tend to be net creditors and the poor tend to be net debtors. Just focusing on “the 1% versus grandpa and grandma” is demagoguery that I wouldn’t associate with economists of the calibre of you and Edmund Phelps (one of my favourite Nobel Prize winners).

LikeLike

I am profoundly skeptical of all macro-models — too much is abstracted away. The pre-2008 Fed model had no financial sector for instance. It now has a stick figure one. So I dont know whether or not the Fed is “creating a permanent reduction in real interest.”

I think its plausible to believe that stock prices are much higher and CD rates are much lower than would have been the case without QE and ZIRP. How much and for how long, who knows.

Savers/creditors are not a homogenous class. The grandpa and grandma that I have in mind (sensibly) own CDs, not stocks. Conversely the 1% dont live off CD cash flow. (This was also in an earlier draft but there is only so much that can be accomodated in an oped)

I dont think its a surprise that my Wall Street friends, virtually to a man (they are all men) think Ben Bernanke has done a wonderful job and except for the recent hiccup he does very well in polls of finance professionals. On the other side its not coincidence that in the general public the standing of the Fed has fallen to levels comparable to that of the IRS and a hair above that of Congress. At least according to Gallup polls.

You may call all this demagoguery. Id argue that the legitimacy of public institutions and collective actions ought not to be sacrificed in the name of speculative theories and models. This is not an argument either for anarchistic libertarianism or against any interventions where there isn’t hard proof of efficacy. Rather its an argument for institutions that give due regard to a broad set of interests and beliefs.

For all its defects (inaction on global warming and gun control are high on my list) Congress has did less harm than Bush’s capricious Iraq adventure and the maestro-Greenspan’s Fed. And if one wants to look for “politically independent” institutions that unlike the Fed fit my criteria of adequate checks and balances, restraint (but not stasis) and legitimacy the judiciary is a pretty good model.

LikeLike

Their analysis fails on every level: By at lead doing enough though QEs to avoid deflation and anchor inflation expectations at 200 bps, real household net worth is up $15t since the advent of QE1 whereas the conference board’s present situation confidence index has risen to 69 from 22, more than a threefold increase.

So QE has worked to partially restore real wealth and confidence; doing less of it would mean less wealth, confidence and growth. Just look at the eurozone, people.

Epic, epic FAIL on the part of Phelps who should be ashamed of himself for attaching his name to such a ridiculous and errant editorial.

LikeLike

Amar,

“Changes in (*estimates* of) total wealth do not rebut the charge of perverse redistribution from grandma and grandpa to the top 1%. Nor does bringing up bad fiscal policies.”

Huh?? First, I would prefer “estimates” to demagoguery and anecdotes. Second, you seem to forget that for every lender that want’s higher interest rates there has to be a borrower that is willing to pay higher interest rates – duh!. For certificate of deposits that means that private borrowers must be willing to pay higher interest rates – except that private borrowers are deleveraging (reducing debt).

You could look to the federal government to begin paying higher interest rates on its debt, but that only means that it must collect more in tax revenue to make those interest payments.

Bringing up bad fiscal policies DOES rebut the charge of perverse distribution because that perverse distribution originates at the fiscal level.

LikeLike

So ZIRP/QE have had no effect on CD rates (or distributional effects) and Grandma and Grandpa are just getting Wicksell’s natural rate of interest? I suppose there is a rational expectations model that could lead to this inference but Ned and I do not believe in rational expectations.

LikeLike

@David Glasner,

“To begin with, the first QE program was not instituted until March 2009 after the target Fed funds rate had been reduced to 0.25% in December 2008.”

Actually the Bhide and Phelps chronology is consistent with the one that is most commonly accepted. See for example this timeline by Bill McBride:

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/09/qe-timeline-update.html

Or this event study by Arvind Krishnamurthy and Annette Vissing Jorgensen:

Click to access 2011_fall_bpea_conference_krishnamurthy.pdf

LikeLike

@Amar Bhide,

“Changes in (*estimates* of) total wealth do not rebut the charge of perverse redistribution from grandma and grandpa to the top 1%.”

Interest income is one of the most unequally distributed forms of income that there is.

According to Edward Wolff, in 2007 the top 1% in net wealth held 34.6% of the net wealth. It’s true they only held 20.2% of the demand, savings and time deposits, money market funds and certificates of deposit (the bottom 90% held 42.3%) and they held 38.6% of the stocks directly or indirectly held (the bottom 90% held 18.8%). But they also held 60.6% of the corporate bonds, government bonds, open market paper and notes (the bottom 90% only held 1.5%).

Click to access wp_589.pdf

And according to the IRS, and data supplied by Emmanuel Saez, approximately 45.7% of the taxable interest income went to the top 1% in income in 2010. For comparison the same data shows that the top 1% in income had 19.9% of all taxable income including capital gains.

LikeLike

You make my point. The top 1% earned a very nice capital gain on their stock and bond holdings and they do not need to live of the interest on their CDs to make ends meet.

LikeLike

Amar,

“Grandma and Grandpa are just getting Wicksell’s natural rate of interest?”

They are getting a money rate of interest the Federal Reserve believes will promote the expansion of credit while not forcing fiscal policy changes to be made. The real or “natural” rate of interest they receive is realized after the money is lent.

I am not saying that ZIRP/QE has had no effect on CD money rates of interest. When a bank only charges 3% interest on a loan, it must pay out less in interest on its CD’s to remain in business.

What you should look at is how fiscal policy (the source of distributional effects) applies to the servicing of private debt.

LikeLike

Marksadowski,

“And according to the IRS, and data supplied by Emmanuel Saez, approximately 45.7% of the taxable interest income went to the top 1% in income in 2010.”

Could that be because the bottom 99% hold much more in tax deferred accounts (pensions, retirements, 401k plans, etc.) while the top 1% are typically self employed or business owners? What are the numbers for tax deferred interest income?

LikeLike

“They are getting a money rate of interest the Federal Reserve believes will promote the expansion of credit while not forcing fiscal policy changes to be made.”

In other words the Fed has chosen to sacrifice Grandma and Grandpa’s interests for the greater common good — using models and theories whose track record has been less than stellar.

LikeLike

Amar,

“In other words the Fed has chosen to sacrifice Grandma and Grandpa’s interests for the greater common good — using models and theories whose track record has been less than stellar.”

NO. Anytime Congress wants to pre-empt the Federal Reserve, that is completely within their power. If Congress wants nominal interest rates to be 10% instead of 1%, all they need to do is raise the tax revenue to support the 10% interest payments (or cut other spending) and tell Treasury Secretary Lew to begin selling non-marketable government bonds with a 10% interest rate. Interest rates on marketable securities will adjust upwards to compete and CD rates may rise.

LikeLike

Quite so. Congress did a great disservice in deferring to the executive in the case of the Iraq War and in delegating sweeping powers to the Fed in pursuit of impossible mandates. Its high time that Congress reconsidered the mission, powers and governance structure of the Fed — and not leave these matters to experts.

LikeLike

Amar,

(With sigh of relief)….At last we agree. The power to regulate to the nominal cost of money (the nominal interest rate) ultimately lies with the Congress.

And what should be apparent is that Congress also has the ability to regulate the after tax cost of servicing private debt (borrower pays nominal interest to CD holder, but after tax cost of servicing the debt backing the CD can be significantly lower than nominal rate).

“… and in delegating sweeping powers to the Fed in pursuit of impossible mandates.”

The mandates themselves are not impossible. They are impossible for the Fed to achieve on its own. That is why I brought up the balance sheet effect that Fed policy has had and that is why I brought up dysfunctional fiscal policy (both tax and spending).

“It’s high time that Congress reconsidered the mission, powers and governance structure of the Fed — and not leave these matters to experts.”

It is high time that Congress recognized it’s own role in regulating the cost of money (nominal and after tax).

LikeLike

Amar, Thanks for responding to my post and engaging in a lively discussion. Thanks also for clarifying that you were not calling for further reductions in inflation. I think that part of the problem with your piece is that you tried to cover two (possibly three) different topics into one op-ed, which accounts for the disjointedness that I complained about. If you are uncomfortable responding on behalf of Phelps, I certainly understand, but how excactly would he recommend that the Fed go about countering falling inflation expectations?

If you go back and look at some of my posts over the past two years, you will see that I have been critical of Bernanke and the FOMC arguing that their monetary policy was aimed at reducing long-term interest rates and increasing stock prices as the mechanism for increasing spending. So I am not entirely unsympathetic to your criticism. However, if what is causing the recession is that the yield on real capital has fallen because of entrepreneurial pessimism, the only way to shock the system onto a higher growth path is reduce real interest rates via inflation to make investing in real capital more attractive than holding CDs. Reducing real interest rates implies rising asset values. (By the way, don’t retirees benefit from increases in the value of their bond portfolios? It’s also possible to shift out of low-yielding CDs and into very safe high-dividend stocks.) Once the inflationary shock therapy is administered, entrepreneurial pessimism is likely to abate, causing the anticipated yield on real capital to rise. The extreme conservatism (small “c”) of the FOMC has prevented them from embracing such a strategy explicitly and they have continued to avoid even the slightest acknowledgement of a need for a temporary increase in inflation or the rate of nominal GDP growth, so we have been stuck in a low-level, low-employment, quasi-equilibrium since 2009. I have no doubt that you are sincere in your concern about the distributional effects of low real interest rates on savers and retirees as opposed to owners of stocks, but in the situation that we are in it is folly to allow distributional concerns to trump recovery concerns. There is no natural right to a minimum real bond yield.

W. Peden, Ok I admit it: I’m bad. But careful, you are coming dangerously close to confusing real and nominal interest rates.

Tommy, We don’t have perfect institutions, and there is much to criticize in the Fed’s performance since 2009 (forget about its catastrophic performance in 2008), but you are surely correct to point out that without QEs, we would not have had even the pseudo-recovery of the last four years.

Amar, There is no unique Wicksellian natural rate of interest. The Fed may have influence over the real interest rate in the sense that it could enforce a higher nominal rate if it chose to, but that would affect the rest of the economy as well. You can’t take the state of the economy as given when you assume that Fed changes its target interest rate. In a well-functioning economy, the Fed would be unable to force a reduction in real interest rates, because nominal interest rates would rise along with inflation expectations induced by the attempt to hold down interest real interest rates. The failure of that mechanism to operate now is evidence that the Fed in not imposing a low real interest rate on the economy, but is a reflection of entrenched entrepreneurial pessimism. The solution would be for the Fed to tolerate a temporary rise in inflation and inflation expectations, but the Fed seems to be institutionally incapable of taking such a step without the support of either of the political branches.

Mark, Thanks for the links. I guess that you are correct that QE started already in late November of 2008. However, the QE was ratcheted up by an order of magnitude by the FOMC at its March 18, 2009 meeting. That’s what I was referring to

LikeLike

@Frank Restly,

I do not have a more detailed breakdown of interest income at my fingertips, so I would have to research the matter further to give you a detailed answer. However, tax deferred does not mean it is never taxed, so I am very skeptical that would make one wit of difference, especially given the highly skewed distribution of interest earning assets.

When thinking of interest income, as when thinking of all forms of capital income (capital gains, dividends, interest, rent), the first thing that should pop into your mind is a Thomas Nast cartoon image of Rentiers, not a picture of of your dear old grandma and grandpa.

LikeLike

David,

“There is no natural right to a minimum real bond yield.”

“However, if what is causing the recession is that the yield on real capital has fallen because of entrepreneurial pessimism, the only way to shock the system onto a higher growth path is reduce real interest rates via inflation to make investing in real capital more attractive than holding CDs.”

Is there a natural right to higher growth (real or nominal)? Or employment? All of these are economic policy decisions.

Presumably the borrower on the other side of the CD has invested in real capital and so you have competing concerns – the borrower who would like his real capital to have a higher value than his debt liability and the lender (CD) owner who would like to have the return on the CD be larger than the value of goods he uses the interest payments to purchase.

The only way to satisfy both concerns is through fiscal (not monetary) policy.

LikeLike

David,

“The Fed may have influence over the real interest rate in the sense that it could enforce a higher nominal rate if it chose to…”

Probably nitpicking, but the Fed can enforce the price of existing bonds by buying and selling them in the market. The Fed can enforce the overnight cost of funds that it will lend at. The Fed cannot enforce a higher nominal rate that is borrowed at. That requires agreement between both borrower and lender.

LikeLike

Marksadowski,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Nast

Thomas Nast made his living for Harpers Weekly exposing corrupt politicians like Boss Tweed and his minions at Tammany Hall during the late 1800’s.

A few other things about Nast:

“Harper’s Weekly, and Nast, played an important role in the election of Ulysses Grant in 1868 and 1872; in the latter campaign, Nast’s ridicule of Horace Greeley’s candidacy was especially merciless. After Grant’s victory in 1872, Mark Twain wrote the artist a letter saying: Nast, you more than any other man have won a prodigious victory for Grant—I mean, rather, for Civilization and Progress.”

“Nast was for many years a staunch Republican. Nast opposed inflation of the currency, notably with his famous rag-baby cartoons, and he played an important part in securing Rutherford B. Hayes’ presidential election in 1876.”

LikeLike

I respect Mr. Bhide for participating in this forum, and his heart seems in the right place.

But…one cannot conduct monetary policy to cater to any one group, such as elderly savers. Monetary policy has to be a macroeconomic policy.

Anything the federal government does—-fight wars, tax income, restore forests—-will help and hurt someone.

But the macro decisions have to be made on the basis of the whole, not a selection of special interests.

I am very willing to assist bona fide poor people; would love to see taxes on luxury goods and PIGOU taxes used to that effect. No one should starve or be denied medical care in our nation.

Besides that, without QE I think we do a Japan, and long-term ZLB and perma-recession hurt nearly everyone.

The reckless, dangerous course would be for the Fed to not do QE, or do it but keep talking about not doing it. We are in the latter position now.

LikeLike

“Monetary policy has to be a macroeconomic policy.”

“without QE I think we do a Japan, and long-term ZLB and perma-recession hurt nearly everyone.”

These are opinions: the second reflecting a particular view or model from which you infer the counterfactual. The first is presumably combines values (Hamiltonian v Jeffersonian) and an instrumental theory.

I happen to have different opinions, and very possibly values. I daresay if you looked around you would find dozens possibly hundreds of different opinions on this subject with no objective way of picking the “right” one.

One big question is how do you reconcile these differences? Who gets to decide, how are the decisions reviewed, etc etc. Another question is, if there is collateral damage, do we compensate the losers, and how? With real property for instance we have a process that allows the state to seize assets under the doctrine of eminent domain while requiring fair compensation for the owners. On the other side vigorous enforcement of anti-trust laws can lead to workers losing their jobs but we dont have a mechanism for compensating them.

Our opinion — and thats why its called an op(inion)-ed is that US monetary arrangements have evolved in an undesirable direction. and we need to rethink them. And this is not in the main a technical argument though inevitably technical issues did feature.

LikeLike

Amar,

“Our opinion — and thats why its called an op(inion)-ed is that US monetary arrangements have evolved in an undesirable direction.”

And there is nothing wrong with that opinion. My own opinion is that monetary policy does not operate in a vacuum. The Fed through its discount rate setting mechanism can lend at any interest rate it likes by decree. The Federal government through its ability to collect tax revenue can pay any interest rate that it likes. The problem is reconciling the differing interests of private creditors and debtors.

“I daresay if you looked around you would find dozens possibly hundreds of different opinions on this subject with no objective way of picking the “right” one.”

Actually, Congress did pick the “right” one, in the sense that they set some macro-economic goals for this country:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humphrey–Hawkins_Full_Employment_Act

Benjamin,

“Monetary policy has to be a macroeconomic policy.”

“I…would love to see taxes on luxury goods and PIGOU taxes used…”

You would prefer macro monetary and micro tax policy. I would prefer macro monetary and macro tax policy.

LikeLike

“Actually, Congress did pick the “right” one, in the sense that they set some macro-economic goals for this country”

Humphrey-Hawkins is a law, not a constitutional amendment. And even constitutional amendments can be repealed.

Ned and I question the macroeconomic mandates of H-H including, (speaking for myself, Im not certain of Ned’s views on this) the price stability mandate without questioning what I think were the aims of the 1913 Act.

LikeLike

Amar,

“Humphrey-Hawkins is a law, not a constitutional amendment.”

And the distinction is important because?

The resolution for nonpayment of private debts is defined by law, not by a constitutional amendment .

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Title_11_of_the_United_States_Code

How exactly do interest rates work for CD’s when the debtor making payments to the CD recipient can just say – “I only recognize the Constitution and it’s amendments, not all these other laws.”

“Ned and I question the macroeconomic mandates of H-H.”

You question them because you believe they are not all simultaneously achievable or you question them because you feel that monetary policy should not be directed toward those particular goals?

LikeLike

“And the distinction is important because?”

The distinction is not vital — I raised it only because laws are more easily repealed/changed and therefor less once and for all.

“You question them because you believe they are not all simultaneously achievable or you question them because you feel that monetary policy should not be directed toward those particular goals?”

The latter with the proviso, that if what I think of as the more primitive functions of central banking (lender of last resort, a substitute for the interbank market in times of stress and enforcer sound banking practices) are effectively performed it would contribute to the stability of employment and prices.

This follows from a world view that in William James’s characterization is empiricist/pragmatist rather than rationalist.

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5116

LikeLike

@Frank Restly,

With respect to Thomas Nast you’ve managed to spectacularly miss the point. Nast was also famous for drawing cartoons like the following:

http://counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.com/2009/08/senate-of-trusts.html

LikeLike

Amar,

This is of particular interest:

“and enforcer of sound banking practices”

What are sound banking practices? What role should banking play in an economy so that we can judge whether banks are soundly operated?

As for profit enterprises? Is it the central bank’s role to enforce profitability?

As an intermediary between creditors and debtors (your CD example)? Is it the central bank’s role to enforce credit intermediation?

As an extension of fiscal policy (see primary dealers)? Is it the central bank’s role to enforce the financing of public deficits?

LikeLike

Frank:

1.I have written a whole book about banking regulation that did not alas take off like a house on fire!

2. I think there is in the normal course little need to “force” banks to lend if their funding sources are secure (hence the need for deposit insurance and rules to discourage reliance on wholesale funding). Rather the problem usually lies with preventing a race to the bottom in credit standards.

2. Right now I suspect that the low levels of commercial credit extension are as much a function of the atrophied ‘capacity’ of banks to make such loans as their risk aversion. As I argued in my book and briefly suggested in the oped TBTF banks have become securitization (mainly of mortgages) and derivative machines, limiting the effects of monetary easing.

4. If I had my druthers I would insulate the central bank from any responsibility for financing the public debt and limit the capacity of the Treasury to stuff bank portfolios with its debt as well. (Reserve requirements are not a necessary feature of a good economic system, as the Canadian example suggests). But thats a pipe dream.

LikeLike

Mark A. Sadowski,

“When thinking of interest income, as when thinking of all forms of capital income (capital gains, dividends, interest, rent), the first thing that should pop into your mind is a Thomas Nast cartoon image of Rentiers, not a picture of of your dear old grandma and grandpa.”

And of course Thomas Nast lived in a time where access to those forms of capital income was severely restricted. There were no retirement and pension plans, certificates of deposit, etc.

“With respect to Thomas Nast you’ve managed to spectacularly miss the point. Nast was also famous for drawing cartoons like the following”

No, I didn’t miss the point. I responded with a counterpoint – Thomas Nast lived during a different time in history. And if you know your history, you know that Ulysses Grant and Congress passed the coinage act of 1873 and the resumption act of 1875.

We can argue whether rentierism (or capitalism if you prefer) results in better economic progress or we can argue whether crony capitalism (gains are accumulated by select few) worsens economic progress.

Nast was editorializing crony capitalism (Boss Tweed and such).

LikeLike

Frank Restly,

Fact: Interest income is highly concentrated.

End of discussion.

LikeLike

Frank (and others): I didnt think my simple link would blow up into a oversized graphic. Sorry about that. (and I dont know how to edit it out now)

LikeLike

A long comment tread! It gets an A for civility, something very rare in this media. Maybe it´s because Hawtrey is giving every one his ‘penetrating stare’!

LikeLike

Indeed inflation has stayed around the 2 percentage mark, but sooner or later it has to go up. It’s remarkable that it has not gone up. Considering the massive amount of money printing. I guess for the time being inflation is not an issue at all.

LikeLike

Tas von Gleichen,

As you know, economics is about supply AND demand. We can’t just look at the supply of base money; we have to look at the demand as well i.e. the velocity.

10-year TIPS are below 1% and 30 year TIPS are below 1.5%. Inflation really doesn’t look like becoming a problem in the US for quite some time.

LikeLike

Amar-

Thank you for your comment.

But I still believe monetary policy is macroeconomic policy, I do not see how this is disputable. I suppose we can get into semantics, but I do not think this is my opinion.

Of course, I am presenting an opinion that without QE we do a Japan. I cannot prove that. But Japan’s longest postwar expansion coincided with their 2001-6 QE program. John Taylor gushes about this QE program on his website. You have to go to papers published in 2006.

I am of the opinion we really should pull out all of the stops, go to tapering up. More QE every month until certain growth and employment targets are hit. After Japan ceased QE in 2006, it went right back into ZLB-deflation-perrma-gloom.

In my opinion, the risk is a dithering, untransparent Fed, that does not lay out an aggressive and clear growth program. The market should have no uncertainty that the Fed means to print a lot of money.

A boom of growth and moderate inflation would do more for those elderly savers than anything else I can think of…..

LikeLike

@Benjamin

“I still believe monetary policy is macroeconomic policy, I do not see how this is disputable. I suppose we can get into semantics, but I do not think this is my opinion.”

I cant find my quote above but I think I was referring to monetary control rather than monetary policy. The latter is indeed commonly conceived of as a a macro matter; the former doesn’t have to be.

Think of “control” vis a vis a truly laissez faire system of money creation (that Im not in the least bit endorsing). Regulating or controlling money in fractional can be done at the macro or micro level. The macro-levers are the ones that get most of the attention (control of the base currency, uniform reserve requirements, open market operations..). But money creation under fractional banking is also affected by decentralized supervision of lending. If examiners are generally tight less will be created for instance. I have no reason to think that a greater reliance on decentralized control would be worse than centralized control and I can see important advantages over a one size fit all macro policy.

“Of course, I am presenting an opinion that without QE we do a Japan. I cannot prove that. But Japan’s longest postwar expansion coincided with their 2001-6 QE program. John Taylor gushes about this QE program on his website. You have to go to papers published in 2006.”

I can only respond with Keynes’s observation that

“If we speak frankly, we have to admit that our basis of knowledge for estimating the yield ten years hence of a railway, a copper mine, a textile factory, the goodwill of a patent medicine, an Atlantic liner, a building in the City of London amounts to little and sometimes to nothing; or even five years hence. In fact, those who seriously attempt to make any such estimate are often so much in the minority that their behaviour does not govern the market.”

Somehow people (Keynes included) ignore their ignorance when it comes to pronouncing on what will happen because of such and such policy.

But if one does admit that no one really knows then one wants to be very careful about sacrificing the interests of vulnerable groups in the belief that they will be better off in the long run without offering them voice or recourse. After all as Keynes also said in the long run we are all dead.

LikeLike

Benjamin,

“A boom of growth and moderate inflation would do more for those elderly savers than anything else I can think of…..”

Let me repeat what David has asserted:

“There is no natural right to growth.”

LikeLike

Amar-

Thanks for your comments. I guess we have talked it out. Really, I don’t care what we do as long as we get a robust economic growth.

Frank-

Well, maybe the population is not “entitled” to economic growth. But surely the population is entitled not to live with a monetary noose tied around its neck, courtesy of the Fed.

LikeLike

But it says in the Metzler paper: ‘In short, the final result of the open-market security purchases by the central bank is a reduction in the real value of the total wealth in private hands’ (p. 110). This seems to agree with the quoted passage of Bhide and Phelps.

LikeLike

Benjamin,

“But surely the population is entitled not to live with a monetary noose tied around its neck, courtesy of the Fed.”

Hyperbole.

LikeLike