In today’s Wall Street Journal, Harold Cole and Lee Ohanian try to teach us some lessons from the Great Depression. According to Cole and Ohanian, those of us who believe that increasing aggregate demand had anything to do with recovery from the Great Depression are totally misguided.

[B]oosting aggregate demand did not end the Great Depression. After the initial stock-market crash of 1929 and subsequent economic plunge, recovery began in the summer of 1932, well before the New Deal. The Federal Reserve Board’s Index of Industrial Production rose nearly 50% between the Depression’s trough of July 1932 and June 1933. This was a period of significant deflation. Inflation began after June 1933, following the demise of the gold standard. Despite higher aggregate demand, industrial production was flat over the following year.

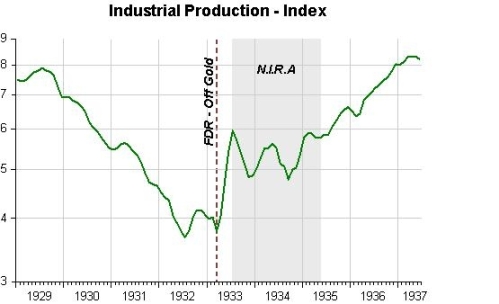

Though not wrong in every detail, the version of events offered by Cole and Ohanian is still a shocking distortion of what happened before FDR took office in March 1933. In particular, although Cole and Ohanian are correct that the trough of the Great Depression was reached in July 1932, when the Industrial Production Index stood at 3.67, rising to 4.15 in October, an increase of about 13%, they conveniently leave out the fact that there was a double dip; industrial production was flat in November and started falling in December, the Industrial Production Index dropping to 3.78 in March 1933, barely above its level the previous July. And their assertion that deflation continued during the recovery is even farther from the truth than their description of what happened to industrial production. When industrial production started to rise, the Producer Price Index (PPI) increased almost 1% three months in a row, July to September, the only monthly increases since July 1929. The PPI resumed its downward trend in October, falling about 9% from September 1932 t0 February 1933, at the same time that industrial production peaked and started falling again.

That is why most observers date the trough of the Great Depression in the US not in July 1932, but in March 1933 when FDR took office in the midst of a banking crisis that threatened to drive the US economy even deeper into deflation and depression than it had been in July 1932. So when Cole and Ohanian assert that recovery from the Great Depression started in July 1932, and go on to say that the recovery took place during a period of significant deflation, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that they are twisting the facts to suit their own ideological predilection.

The misrepresentation perpetrated by Cole and Ohanian only gets worse when they describe what happened during the period of true recovery, April through July 1933. Contrary to their assertion, deflation stopped in February 1933, the PPI hitting its low point of 10.3. Prices began to rise as soon as FDR suspended the gold standard shortly after taking office in March (not June as Cole and Ohanian mistakenly assert) 1933, the PPI rising to 11.9 in July (an increase of about 14% over February) when industrial production hit a peak of 5.95, 57% above the March low point.

The two attached charts (supplied courtesy of Marcus Nunes) illustrate the sequence of events that I have just described. The close correlation between the PPI and industrial production is especially striking.

To assert that the rapid price increases from March to July, a proxy for increased aggregate demand, played no role in what was then (and remains) the fastest increase in industrial production in any four-month period in American history is a gross misrepresentation of the facts. What is perhaps even more shocking is that Cole  and Ohanian would misrepresent facts so easily ascertainable.

and Ohanian would misrepresent facts so easily ascertainable.

Nevertheless, not everything Cole and Ohanian say is wrong. They properly criticize New Deal policies that slowed down the spectacular recovery from April to July 1933 to almost a crawl. What stopped April to July recovery almost in its tracks? The answer is almost certainly that FDR forced his misguided National Industrial Recovery Act through Congress in June, and by July its effects were beginning to be felt. Simultaneously forcing up nominal wages in the face of high unemployment (though unemployment started had falling rapidly when recovery started in April) and cartelizing large swaths of the American economy, the NRA effectively shut down the recovery that was still gaining momentum. As shown in the chart representing industrial production, industrial production resumed its rapid expansion almost immediately after the NIRA was unanimously struck down by the Supreme Court in May 1935. The aborted recovery was a tragedy for the American economy and for the world, but the premature end of (or extended pause in) the recovery tells us nothing about whether an economy can recover from a depression with no increase in aggregate demand.

Another point overlooked by Cole and Ohanian, presumably because it doesn’t exactly fit the ideological message that they want to propagate, is that the timing of the recovery — immediately after the monetary stimulus resulting from suspension of the gold standard – shows that monetary policy can be effective with little or no fiscal stimulus. It is hard to see how any fiscal stimulus could have taken effect by April 1933 when the recovery had already begun. Moreover, Roosevelt campaigned as a fiscal conservative, so it would not be easy to argue that anticipated fiscal stimulus was being felt in advance of its actual implementation.

The real lesson the Great Depression is that monetary policy works — for good or ill.

HT: Bill Woolsey, Marcus Nunes, Scott Sumner

Thanks goodness for the Internet, a valuable medium to expose simple canards, such as those foisted off on the public by Cole (no relation) and Ohanian (really no relation).

What is the purpose of these endless assaults on effective monetary policy? What is this peevish zeal to bring measurable inflation to zero, at huge costs to real output? Why this perverted worship of gold?

At best, we can hope this is simple posturing until we get a GOP president, at which time the WSJ will editorialize it is time to ramp things up again.

At worst, some right-wingers really believe this demented ranting about gold and tight money, and thus they will be a threat to USA security and prosperity for a long, long time. What if the GOP wins and the gold-fetishists assume policy positions?

Japan here we come—or maybe Hoovervilles-R-Us.

And not, I am not a liberal. My favorite economist is Milton Friedman.

LikeLike

David

Great “smackdown” on “ideologigal bias”! One correction:”Contrary to their assertion deflation stopped in February 1933 (not 1932).

LikeLike

I hadn’t realised how strong and immediate the effects of going off gold were, Those charts tell a very compelling story.

Hmmm. Maybe Scott is right about those long and variable lags being very short indeed.

And, as I understand it, nothing much at all was happening to interest rates on government bonds after FDR went off gold, right?

LikeLike

I’m disgusted at how people can be so dishonest, but unsurprised that it was people writing for The Wall Street Journal.

LikeLike

Let me see: no mention of Emergency banking act, the bank holiday–all of which were done before the act of confiscating gold and two months before devaluing the dollar in terms of gold?

The issues are more complicated than “expand the monetary base” and voila there are no lags, it is instantaneous. Promising a credible lender of last resort, and having deposit insurance is not the same as expanding the base when financial conditions have stabilized.

LikeLike

Glassner says “The real lesson [of] the Great Depression is that monetary policy works — for good or ill.”

Freezing and revaluing gold is not exactly what is understood by modern monetary policy. The evidence permits the hypothesis that closing the banks and freezing/revaluation were critical events in the turnaround, but obviously the circumstances then were very different from anything since; other countries had abandoned gold and there were continual bank runs, which are now practically non-existent because of Glass-Steagall. It was Glass-Steagall and the action on revaluation by Roosevelt and Congress which saved the banks and probably keyed the turnaround, not monetary policy action by the Fed.

In the real world of Fed monetary policy, the Fed started cuttting rates in August 2007 – did that prevent the financial collapse and recession or cause an instant turnaround? Glassner answers the WSJ nonsense with more nonsense of his own about monetary policy.

LikeLike

You can not trust the growth rates of an index with different bases, called the Gershenkron effect, where you can not compare indexes with different base years. In addition if you use a modern base in order to see growth in 1931 – the growth rates of dates a long way from your base have higher than possible growth rates (if it a leaspayres index).

LikeLike

Just more falsehoods from our version of the Taliban. There are objective facts. Deal with them. Do not ignore or lie about them.

LikeLike

this blog would be a lot more convincing if you had a simple graph, what cole said, what the graph said…way to many words to carry the poitns

LikeLike

Glasner should refrain from commenting publicly about things he does not understand. That goes for the rest of you, too.

LikeLike

David, great post…it is incredible that anybody would put their names on a piece like the one Cole and Ohanian have produced. Your two graphs clearly illustrates how potent monetary policy can be – and how damaging the wrong supply side policies can be.

One thing which is really puzzling how they can say that the Great Depression is a negative supply shock when we had massive deflation – not exactly textbook…

LikeLike

Nick, of course Scott is right. Monetary policy is extremely potent and works with short or no lags at all. By a look at the market reaction to the devaluation is also extremely impressive – US stock rallies very strongly from the day FDR takes the US off gold…

LikeLike

By the way it should be remembered that a Market Monetarist perspective on the devaluation would be that the devaluation might actually have an positive impact even BEFORE it actually happened. As Scott Sumner like to remind us – monetary policy works with long and variable LEADS.

The speculation about FDR pursuing anti-deflation policies was clearly on the rise already in 1932.

LikeLike

Excellent post, David.

And Marcus’ charts are very compelling, showing the potency of monetary stimulus as well as the harm that NIRA did.

LikeLike

skeptonomist,

Looking at nominal interest rate movements is an extraordinarily naive way of examining monetary policy.

LikeLike

@Skeptonomics: You wrote:

“In the real world of Fed monetary policy, the Fed started cuttting rates in August 2007 – did that prevent the financial collapse and recession or cause an instant turnaround? Glassner answers the WSJ nonsense with more nonsense of his own about monetary policy”.

No, it didn´t do an instant turnaround because, despite the interest rate cuts, MP was still contractionary! Hard to understand? Read this:

LikeLike

Benjamin, Bad monetary policy had tragic consequences in the 1920s and 1930s, so the stakes are indeed very high, but all the same, watch your blood pressure.

Marcus, Thanks and thanks again for the graphs.

Nick, Listen to Lars. I haven’t looked up interest rates, but I think they stayed pretty low for a very long time.

Tyler, It was Krugman who accused them of writing in bad faith. I don’t know what their motivation was, but they were very sloppy. I am not trying to evaluate their character.

Srini, You are right that I did not write anything like a complete history of the Great Depression in one blog post.

Skeptonomist, There are various ways to conduct monetary policy and manipulating interest rates is only one of them. And I certainly agree that it was FDR who took control of monetary policy from the Fed in 1933 to the great benefit of the US and the rest of the world.

Alex, Thanks for reminding me of (or teaching me about) the Gershenkron effect. However, the correlation between the PPI and industrial production seems so close that it seems hard to imagine that it would be entirely a statistical artifact. How would you go about estimating the magnitude of the effect or possibly correcting for it? Or is that not possible?

mark, I am no fan of the Wall Street Journal, but calling them taliban is just way over the top.

ezra, Thanks for your suggestion, but blogging requires pretty quick turnarounds.

herbert, Thank for that really valuable input.

Lars and Dustin, Thanks for your kind words, I don’t understand why Cole and Ohanian weren’t more careful.

Marcus, Good point.

LikeLike

Dear David,

There are several ways to approach the issue, including a fischer rather than a Laspayeres or Paasche index. Statistical offices used chain linked indexes, but as economic historians we find that this creates problems in longrun series.

The Gershekron effect can be easily corrected if you have the original data.

First pick a common base year for all your indicators (if you can). Secondly if you have a long series (over 150 years/quarters ect.) you correct the series’ growth rate. You pick benchmarks of 50 years and then use those growth rates on the orignal series levels. In effect you smooth out the proportion of the growth rate that is created by simply being far away for a base (which could be as high if the series is long).

You can email me if you want – it is something economic historian take into account all the time.

LikeLike

Dear David,

There are several ways to approach the issue, including a fischer rather than a Laspayeres or Paasche index. Statistical offices used chain linked indexes, but as economic historians we find that this creates problems in longrun series.

The Gershekron effect can be easily corrected if you have the original data.

First pick a common base year for all your indicators (if you can). Secondly if you have a long series (over 150 years/quarters ect.) you correct the series’ growth rate. You pick benchmarks of 50 years and then use those growth rates on the orignal series levels. In effect you smooth out the proportion of the growth rate that is created by simply being far away for a base (which could be as high if the series is long).

You can email me if you want – it is something economic historian take into account all the time.

Thank you for answering

LikeLike

These aren’t growth rates.

These are levels, right?

Of course, they are levels of an index, and so are stated relative to a base year.

Does that make a difference?

I suppose if the argument here was that the PPI went up 5% in 1932 and the Industrial production index went up 5% too, and that was important, then this might matter.

But the argument was just about direction.

Is it possible that because the indexes used different years, the PPI really was going down when the index went up? And that industrial production really went down, when the index of industrial production went up?

Maybe I am wrong, but I am pretty sure the Great Depression wasn’t about slower producer price inflation and slower growth in industrial production.

Where are the growth rates?

LikeLike

I would note that the left of center economists (Krugman, Toma, and DeLong) quoting this post leave out:

“Nevertheless, not everything Cole and Ohanian say is wrong. They properly criticize New Deal policies that slowed down the spectacular recovery from April to July 1933 to almost a crawl. What stopped April to July recovery almost in its tracks? The answer is almost certainly that FDR forced his misguided National Industrial Recovery Act through Congress in June, and by July its effects were beginning to be felt. Simultaneously forcing up nominal wages in the face of high unemployment (though unemployment started had falling rapidly when recovery started in April) and cartelizing large swaths of the American economy, the NRA effectively shut down the recovery that was still gaining momentum. As shown in the chart representing industrial production, industrial production resumed its rapid expansion almost immediately after the NIRA was unanimously struck down by the Supreme Court in May 1935. The aborted recovery was a tragedy for the American economy and for the world, but the premature end of (or extended pause in) the recovery tells us nothing about whether an economy can recover from a depression with no increase in aggregate demand.”

LikeLike

Dear Bill,

Anything that affects growth rates has an effects on levels too – no it will not change the direction, but if the magnitude is important then the further away from the base you are, the least reliable your growth (and hence level) is. Statistical offices correct for this by changing bases often (and correcting as as I explain above) or by chain-linking.

We take indexes for granted, but really they can create very big problems, while index number theory is never taught in graduate school.

LikeLike

First, I would note back to you that this paragraph discusses a few months over several years; perhaps you should have an accurate quantitative perspective.

Second, ‘I would note that the left of center economists (Krugman, Toma, and DeLong) quoting this post leave out:’

Since Krugman has spent years cleaning Chicago’s clock, I’ll accept the obvious interpretation that ‘right of center’ means ‘detached from reality’.

LikeLike

Herbert, considering that right-wing economics is collapsing into a morass of revisionism and straight-out lying, perhaps it’s time for you guys to realize that you don’t know what you are talking about, and to shut up.

LikeLike

Alex, Thanks for elaborating on the point for me. My intuition says that for the purposes that I (and I think Bill as well) am interested in these numbers the effect you are mentioning wouldn’t invalidate the inference I want to make. But obviously my intuition doesn’t count for that much. So the specific question which we may have to pursue off line is what as a practical matter would we have to do to the PPI and industrial production data to address the Gershenkron effect. I at least would need a fairly explicit set of guidelines about how to proceed.

Bill, I think your intuition probably is the same as mine, but to make a solid empirical case, I think Alex’s point would have to be recognized and addressed.

Barry, I think it is fair to point out that Krugman et al. did not quote my post in its entirety but picked out the part of it that was most congenial to their position. There’s nothing dishonest about that, but there is nothing wrong in making that observation, either.

LikeLike

Feel free to contact me by email (alexapostolides at gmail). I think I can see source, and quickly 1) see if it correction to these effects has already been done

2) see how been the effect can be

3) correct it or at least walk you though in how it is corrected.

Note: the effect only changes the amount of growth but not its direction. So i thinks the argument you make is valid

LikeLike

A piece I wrote for the Fall 2009 Cato Journal includes tables showing measures of fiscal and monetary policy. The data clearly confirm Romer’s 1991 finding that, “Monetary developments were very important and fiscal policy was of little consequence in the mid and late 1930s.” But they also confirm Romer and Romer’s later finding, using postwar data, that higher tax rates are highly contractionary. And that, too, contradicts what Cole and Ohanian wrote in 2007.

Click to access cj29n3-11.pdf

I wrote that, “Devaluations in the United States and Britain clearly helped ‘reflate’ the world economy. Most U.S. and foreign tariffs were specific (levied as cents per item or pound), so effective tariff rates were reduced by higher prices. Reflation in Britain also shrank the real value of the dole, boosting work incentives. . . .

Although short-term interest rates were very low throughout the 1930s, the quantity of bank reserves and currency remained critically important during the deflationary period of 1930–33, the mildly inflationary recovery of 1934–36, the 1937 recession, and the subsequent recovery after June 1938. . . .

Mono-causal explanations of the Great Depression are neither necessary nor sufficient. Monetary forces dominated the deflationary periods, 1930–33 and 1938. Yet the strong recovery after June 1938 was mildly deflationary, and the aborted recovery of 1934–36 was mildly inflationary. Moreover, such financial matters as the falling value of collateral for bank loans were surely affected by real events, which include effects of changing tax rates (Shimer 2009) and tariffs on the supply and productivity of labor and capital.

When examining such negative output shocks from higher tax rates in the 1930s, however, Cole and Ohanian (2007: 33) claim, ‘Tax rates on labor and capital changed very little during 1929–33, which implies they were not important for the decline.’ In reality, marginal tax rates were virtually tripled in June 1932, retroactive to January of that year. The lowest marginal tax rate rose from 1.1 percent to 4 percent; the highest from 25 percent to 63 percent. There were also big increases in excise, corporate, and estate taxes (Blakey and Blakey 1932). Because Cole and Ohanian appear unaware of the Revenue Act of 1932, their estimate that ‘higher taxes played a relatively minor role’ surely understates the 1932 fiscal shock.”

LikeLike

Alan, I agree with most of this. However, I would take exception to a couple of points. The recovery actually began in March/April of 1933 immediately after FDR suspended the gold standard and the dollar price of gold began rising in world markets. A blistering recovery ensued until it was prematurely aborted by the NRA and a forced increase in money wages. Further dollar depreciation and increased money wages kept prices rising for a while, which accounts for the inflationary trend in 1934-35. The recovery resumed after the NRA was scrapped in 1935.but most of the growth in output stemmed from the boom in between the departure from gold and the start of the NRA.

LikeLike

I did not mean to suggest that devaluation was not immediately followed by a very strong recovery. I used annual GDP data in the Cato Journal, so I suppose my reference to the “1934-36” recovery was unintentionally misleading about the timing.

I was more explicit about the timing of the 1937-38 slump which almost exactly matched the increase and susequent easing of reserve requirements. Much as I would like to blame higher tax rates in 1936 or regulatory changes, both of the big gyrations in growth from 1933 to 1938 appear primarily monetary in origin.

The modest CPI inflation of 1934-36 was a big improvement over the previous deflation, and I mention it only because it contradicts the Keynesian assumption that slack labor markets make inflation impossible. Obviously not.

My main point here is to suggest that Cole and Ohanian made yet another mistake (about no tax hikes in 1932) and that Glasner, by contrast, is factually correct to emphasize the dominant role of money and the Fed after 1932, though not necessarily before (when trade wars, regulations and tax policy also involved global supply shocks).

LikeLike

Alan, It seemed to me before that we were largely in agreement. Now, happily, it appears we are almost in total agreement. The only point that I would quibble about is that in the 1934-36 episode the increase in wage rates was imposed by government mandate or by a government sponsored enhancement of trade union monopoly power. So the standard Keynesian story about slack labor markets is not necessarily refuted by that special factual situation.

LikeLike

What is important is to have a monetary system not open to manipulation by the people who run it. You cannot reduce the value of gold beyond the marginal cost of production of gold. That is because people want it for other things. Thus you cannot alternately create inflation (and buy real assets) and create deflation (and sell real assets) in order to manipulate the market and eventually manipulate it into leaving you and your friends will (literally) all the property in the world.

I love Friedman too, but I believe that the Austrians had it right when it comes to fiat money. Friedman’s system would work if government could be trusted. It cannot. The Austrian proposal does not require a trustworthy government. Friedman said if he were appointed to the Federal Reserve board he would set the machines to increase the money supply by an even 3% forever. This would be fine. But how long before some politically connected banker talked them into firing you and putting in another Greenspan?

LikeLike

I’m sorry I got to the part of the Cole/Ohanian study where they said we just took the growth factors from the twenties and plugged them into the thirties to come to our conclusion and realized that these were two people who would say anything to protect their theory. They have PhD’s. How can anyone honestly say that they think this is a valid methodology.

LikeLike

There are two essential questions here.

1) Can monetary policy have a short term impact?

2) Is monetary policy the most effective long term policy.

There is no doubt that monetary policy is the most effective response to depression in the short term. It basically kept us out of the 2007 depression, for example.

However monetary policy has a critical weakness – that is, that it looses its effectiveness somewhere around zero interest rate levels.

In a demand-driven depression (as most depressions in right leaning countries are), buying assets to inject more money into the system puts the additional dollars increasingly into the hands of the wealthy, who are not part of the demand problem. If the efficiency drops by half, you can get the same response with twice the stimulus. If the interest rates near zero – you have ZIRP and the crazy money supply graphs that go with that.

Only redistribution, as ugly as that sounds to some, is able to create a mathematical balance that alleviates the problem.

Consider that after 1933, new jobs were added at an unprecedented rate, whereas today, if you look only at the 15-25 demographic, we are practically at depression levels today.

LikeLike

Jeff, The 1933 recovery was largely the result of monetary policy (suspension of the gold standard and devaluation of the dollar and the creation of inflationary expectations), which had little or nothing to do with redistribution. The remarkable four month recovery was more or less stopped in its tracks by the start of the NRA which raised nominal wages and restricted output while the rate of dollar devaluation was slowing down.

LikeLike

David – I find it hard to conclude that when you try a, b, c, and d and things get better that a “must have” worked. I am certainly open to being wrong about which elements of the new deal were most effective.

There are two prevailing theories here as far as I can tell:

1) Labor has a V-shaped supply curve – that is, people offer more hours to the market in both times of greed and fear. The great depression pushed too many individual laborers into the left side of that curve causing the bottom to drop out of demand in a viscous cycle (in addition to the better known issue of near complete loss of capital gains-based demand).

2) Somehow, dropping wages to keep up with deflation could have magically fixed the fact that all capital gains demand was lost and demand had to come out of wages.

Theory two here relies on a logical category error because it tries to use this reified term “inflation” that actually means very different things depending on whether you are talking about prices of goods, assets, or labor. In any period where goods, assets, and labor move in different directions, using this term yields massive problems. A simple way to tease out this problem is to take money out of the picture and assume all workers are paid wages out of the goods they make and a genie comes along and moves all the goods around to where the dollars would have pushed them. It is easy to see with this picture that a good fraction of the goods would just sit and rot in warehouses absent government and capital gains demands causing less labor to be needed in the future. As it turns out this is a pretty good description of what we saw in the great depression.

LikeLike

Jeff, Very little of what we think about when we hear “New Deal” was implented in the April to July 1933 time frame. By far the most important thing that happened was that the gold standard was suspended and the dollar was depreciating rapidly, so I don’t accept that a, b, c, and d were tried. It was just a. And when b was tried and a was stopped or at least scaled back, the recovery stalled.

LikeLike

Thank you for your response.

Looking at 1933, I see two possible catalysts for a large change in growth – monetary policy and the massive tax change of 1932. (I am including the bank holiday in “monetary policy” because its primary goal was to increase liquidity and perceived solvency.)

This falls short of separating out the impact of the tax changes (and the short term confidence boost for consumer demand associated with that) and the impact of monetary policy, and it also makes the claim that the short term growth (1933) and the long term growth (1933-1945) must be driven by the same stimulus.

Further, it would seem to lack a theoretical underpinning (or at least it doesn’t make this underpinning explicit), which is necessary because experiments test models rather than testing free-floating hypothesis.

Given that common sense says that liquidity drives short term spending and income drives long term spending, it seems problematic to discount income effects based on 1933 alone.

LikeLike

Jeff, I really don’t understand what you are saying. The massive tax changes of 1932 were across the board tax increases. How was a massive tax increase a catalyst for growth, either short-term or long-term? And since the tax increase was passed in 1932 what does that have to do with the New Deal? And why do you think a massive tax increase boosted confidence and boosted consumer demand?

You said:

“and it also makes the claim that the short term growth (1933) and the long term growth (1933-1945) must be driven by the same stimulus.”

What is the antecedent of “it?” And what is the relationship between “it” — whatever that may be — and “the claim that short term growth (1933) and the long term growth (1933-1945) must be driven by the same stimulus,” which I don’t recall making myself and don’t recall seeing anyone else making either?

You said:

“it would seem to lack a theoretical underpinning (or at least it doesn’t make this underpinning explicit)”

Again, I don’t know what the antecedent to “it” is.

LikeLike

” How was a massive tax increase a catalyst for growth, either short-term or long-term? How was a massive tax increase a catalyst for growth, either short-term or long-term?”

This is indeed a surprising result of the Reagan legacy. Before Reagan most policy advisers were arguing whether tax cuts or spending increases would stimulate the economy more. As far as I know, no-one was predicting what actually happened – that cutting taxes *while continuing to spend as always before* would have a *negative* stimulus for the economy. Yet that is exactly what happened. During the Reagan presidency, economic growth permanently (at least so far) dropped by about a third in the US.

During the 1920s, just as during the 1980s, spending out of wages dropped precipitously and was replaced by spending out of capital gains. Trickle-down economics can actually be a very powerful economic force as during these periods, dollars shaking loose from the rich were almost able to replace the spending from wages lost during these periods. The key here is *almost*. Witness that growth since 1980 has been about 2/3rds of what it was before instead of massively negative.

Taking this back to subject, starting in the 1980s, we invested heavily in something as evidenced by our massively increasing public debt over this period. What did we get for this investment? A 1/3rd drop in growth. It turns out that economic losses due to inequality can be bigger than the economic gains due to increased monetary stimulus.

So, how can this impossible-seeming situation of tax increases spurring demand occur? The key insight is that money in public hands is a bad logical category. There are some dollars that will be directed to consume and some dollars that will be directed to invest. Assuming that the economy will react to both of these categories equally is in essence implicitly assuming that these will naturally be in balance.

So, how can you tell if these are in balance or not? A shortage of dollars for consumption combined with an excess of dollars for investments pushes rate of return on investment toward zero across a broad swath of investment classes. Hence the broad increases in bond, stock, real estate, and commodity prices as expressed in their products since 1980.

The extra tax on the wealthy decreases the number of dollars aimed at investments and any increased spending on the middle class increases the availability of dollars providing return on these investments, which pushes P/E back toward reasonable levels. Even without the extra spending on the middle class, the increase in taxes on the wealthy impacts currency exchange rates and can mitigate severe trade imbalances and favorably impact the competitiveness of small businesses compared with their larger counterparts, which is beneficial to demand.

So, while it seems counter-intuitive, there is solid historic evidence that increases in progressive taxation have an impact on prosperity counter to the “quantity of money” based predictions and there is a plausible explanation for the same when you dig deeper.

“And since the tax increase was passed in 1932 what does that have to do with the New Deal?”

Fair point, but I would suggest that both are part of the populist movement that accelerated during the Great Depression. Witness the letter writing campaign against the previously planned regressive tax increase that the 1932 progressive taxation replaced.

“And why do you think a massive tax increase boosted confidence and boosted consumer demand?”

There is a joke about three professors who go hunting.

Engineering professor – designs accurate visual scope and hits the place where the deer just was with great accuracy.

Physics professor – calculates lead time and hits the place where the deer would have been if he hadn’t stopped.

Statistics professor – “This is great! On average we had a bulls-eye!”

We cannot think of businesses as merely entities that track the money supply and make projections off if it or we are making the same mistake as the Statistician above. Businesses will make projections based on multiple factors including whether they will have customers and whether they will have the physical capital (Not financial capital, which combines physical capital and asset prices!) to meet the needs of those customers. Obviously which of these factors is the limiting factor will vary with the business climate and projections made in one climate will be useless in another unless these limiting factors remain the same.

Assuming that businesses will always be limited by access to financial capital is an intellectual laziness that guarantees you will take exactly the wrong sort of action in any supply-glut depression.

Business confidence, of course, is the sum across the economy of all of these individual decisions, and any formula that would estimate this must be validated against the over-arching business conditions before you can use it.

“Again, I don’t know what the antecedent to “it” is.”

The ideas that the metaphor of liquidity helping in the short term situation and earnings being the more important factor for the economy in the long term is a bad metaphor for how GDP increases and that when you understand liquidity and monetary policy you can ignore differences between middle class income and income of the .001% in how they impact the economy seem like ideas that would require a model to prove, rather than merely trying to prove based on correlation. After you have the model, you can determine if the correlation is really happening in the right points and you can better establish the significance of the correlation. The model also potentially allows you to predict longer time periods giving you more range of apples-to-apples tests. Ask any physicist and they will say that they test models – not hypothesis – if they are speaking clearly, and the hypothesis are interpreted only within the model containing them.

LikeLike

Jeff, I am sorry, but I really can’t follow your reasoning, so I am unable to respond adequately to what you are saying here. At any rate, taxes were reduced from the very high levels of World War I throughout the 1920s, and until the onset of the Great Depression, growth was fairly robust, so that seems to cut against your hypothesis that increasing tax rates in 1932 caused the 1933 recovery, long after the cuts went into effect. The recovery did not start until after the gold standard was suspended and the dollar devalued, so the timing certainly favors the monetary hypothesis. I actually have suggested in a few posts that reducing taxes might have some role in reducing growth by causing an increase in the size of the financial sector which may adversely affect the rest of the economy by drawing resource into socially unproductive financial activity. But that is a long-run effect.

LikeLike